Rising Rents and Stagnant Wages: Today's Economic Challenges with San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly

on monetary policy, the labor market, and disagreements

I had the incredible opportunity to interview Mary Daly, the President and CEO of the San Francisco Federal Reserve on monetary policy, the labor market, Claudia Goldin, and more. Special thanks to the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

The Interview

Kyla: I want to begin by first talking about the housing situation. So there was a letter from housing centric associations, including the NAHB and the National Association of Realtors asking Jerome Powell to stop hiking rates and to not sell off any mortgage backed securities until the housing market has stabilized. And there's this push pull that's going on with housing, this supply demand misbalance. People who want a home can't get one. How does the Fed balance this housing crisis with policy decisions, especially considering the impact that rate hikes have on mortgage rates?

President Daly: Sure. So, it's a really important question, and it's complicated, but let me start with what the Fed does. We have two congressionally mandated goals - price stability, full employment - and right now we're achieving the full employment goal and missing on the price stability goal.

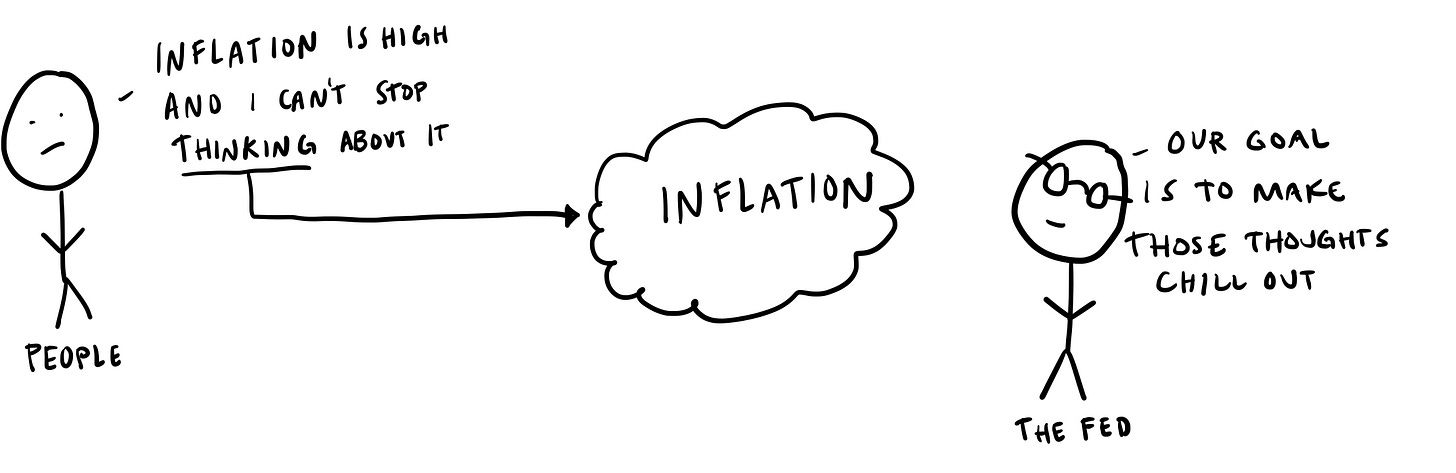

Now, why is that so important? Well, ultimately, low inflation. That 2% target we have is a place where people don't have to think about it. They're not making their decisions based on what's going to happen to inflation tomorrow. But when inflation is above 2% like it is now, and it was even higher before, hitting 7% and we've gotten it down, we've made quite a bit of progress, but when it's high, people are getting up every morning and thinking about inflation, and that's going to affect their decisions.

And one important decision it affects is housing. So yes, mortgage interest rates have risen as we're trying to slow the economy to get demand back in line with existing supply. Let's think before we start at the interest rate tightening cycle. Inflation was rising. Housing inflation was really rising. And so individuals might have had a lower mortgage interest rate, but people with mortgages in some cities weren't even competitive in the market because people were coming paying cash and owning two or three homes.

And the whole housing market was very much out of balance. And I have the nine western states in the United States. Many of those cities, Boise, Idaho, Salt Lake City, those were where the housing prices in the United States were rising most quickly, and first time home buyers were completely priced out of the market.

So what the Fed's job is to get that price stability back in check, have that be that 2% target, and then the housing market will start to rebalance itself. But you mentioned, and it's absolutely important we recognize this as a nation, we have more demand for houses than we have homes ready for occupancy, whether those are rentals or purchase homes.

That's going to cause prices to be elevated and housing markets to be competitive. And what I'm seeing now is many, many discussions across the country about how do we increase the supply. And I was just in Salt Lake City talking to some home builders and they're starting to think about how do we continue to increase supply, just not at the rapid clip we were when interest rates were lower and demand was right around the corner.

And they're also starting to rethink what types of homes they build. Building homes that fit first-time homebuyers price points as opposed to maybe, you know, the third or fourth home that you're buying in your life. And I think that's all what we have to do. But ultimately, the trade off we face is, is one that was given to us by Congress.

Our jobs are very simple. Our mandated goals are price stability and full employment. We're achieving full employment, and we're missing on price stability. And so Congress mandates that we achieve that goal, and that's what we're working towards.

Could the Fed Get in the Way of Supply and Demand Normalization?

Kyla: And it almost feels like there's a new normal that we're facing, like this is a term that gets thrown out a little bit., where maybe we're in a world where inflation does remain kind of high. Um, and historical patterns are not repeated in the way that they always were. And, you know, the Fed has accomplished in, in nine months, what normally takes about a year and a half to do. It's gone really quickly and really, I suppose, impactfully in some sectors of the market, and some would argue that it's not rate hikes doing a lot of the lifting, but supply and demand normalization. So in what way do you think monetary policy would begin to get in the way of supply and demand normalization? Is there something that the Fed is looking at with supply normalizing where it's like, okay, we need to stop hiking rates because it could get in the way of that?

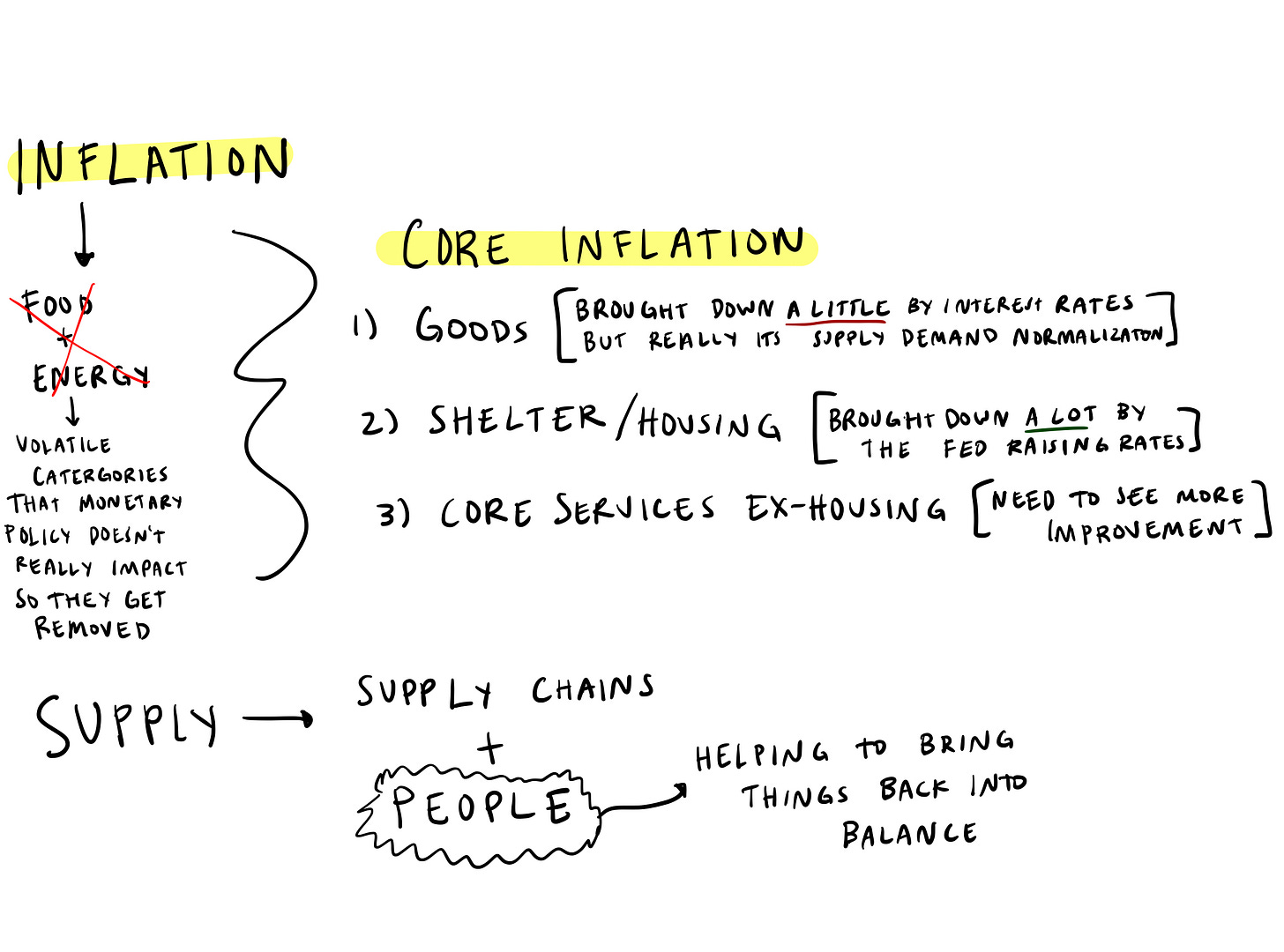

Sure. That’s a nice question. Excellent question. So, the way that I think about unpacking that is that you have overall inflation. And for a moment, let's just go to core inflation, taking out food and energy. I totally recognize that people pay for food and energy.

In fact, those are the high value items that so many people found hard to afford. But ultimately, they're volatile categories and monetary policy doesn't affect them very much. It's more global situations like wars and who wants to produce energy at any given time, global demand. So we just take those two things out, and then we're left with what we call core inflation.

And I like to break core inflation into three components.

Goods inflation

Housing or shelter inflation

Then core services ex-housing. It's often called super core, but basically it's all other services absent shelter services.

And if you look at those things then goods price inflation is coming down the most quickly. But that is almost entirely driven - it's driven a little bit by changes in demand because of interest rates, because interest rates affect durable goods purchases, car purchases, business investment. But it also really gets brought down by the supply chains normalizing. So as they normalize, goods price inflation comes down and that's a good thing.

That's what I would think of as an easy win on the inflation fight and not something that the Fed policy is really the biggest contributor to. That will continue to go down, and where it will stop and whether it will return to its deflationary prepandemic trend is hard to say because there's a lot of things that could keep it a little bit higher, but definitely that's where we've already seen a lot of progress.

The next one where we're seeing progress where the Fed does matter, and you mentioned in your first question is shelter inflation. We started raising interest rates early last year. We had signaled we were going to raise them before mortgage interest rates went up, refinancing went down, and housing price growth started to slow. The whole housing market slowed. That is a direct result of Fed policy raising interest rates. And that is part of why overall inflation is coming down.

And then this third component, services without housing in it. Ex-housing is the stickiest and it's the hardest to come down. It often lags the other two and we're just starting to see some improvement in that sector and we will need to see more improvement to feel like we're really back on a path to 2% but I don't feel like policy is yet interrupting the return of supply and demand - because remember what's driving supply is really the supply chain disruptions from the pandemic and then another part of supply that is often forgotten are people and labor supply is one of the biggest components of supply that we have.

What's really nice is that this long and durable expansion we've been in, as we get inflation down in particular, you've seen people coming back in - labor force participation rates are rising and so that's a very strong help to maintaining a healthy economy and also bringing supply and demand back into balance. So we have more work to do, inflation's still high, but I don't see our policy as interrupting those improvements. I see it as aiding those improvements.

What Could a New Normal Look Like?

Kyla: Going back to this idea of a new normal where rates remain high - like potentially at 5% for a sustained period of time - Bank of America released a report today talking about the five reasons that rates could stay above 5%, including sticky wages, fewer workers, record debt burdens, deglobalization, demographics, and chronic under investment from countries. I know a lot of people ask you about the present moment, but when you look out into the world beyond, do you see a world where these things come to fruition and impact how we interact with the economy and to the future?

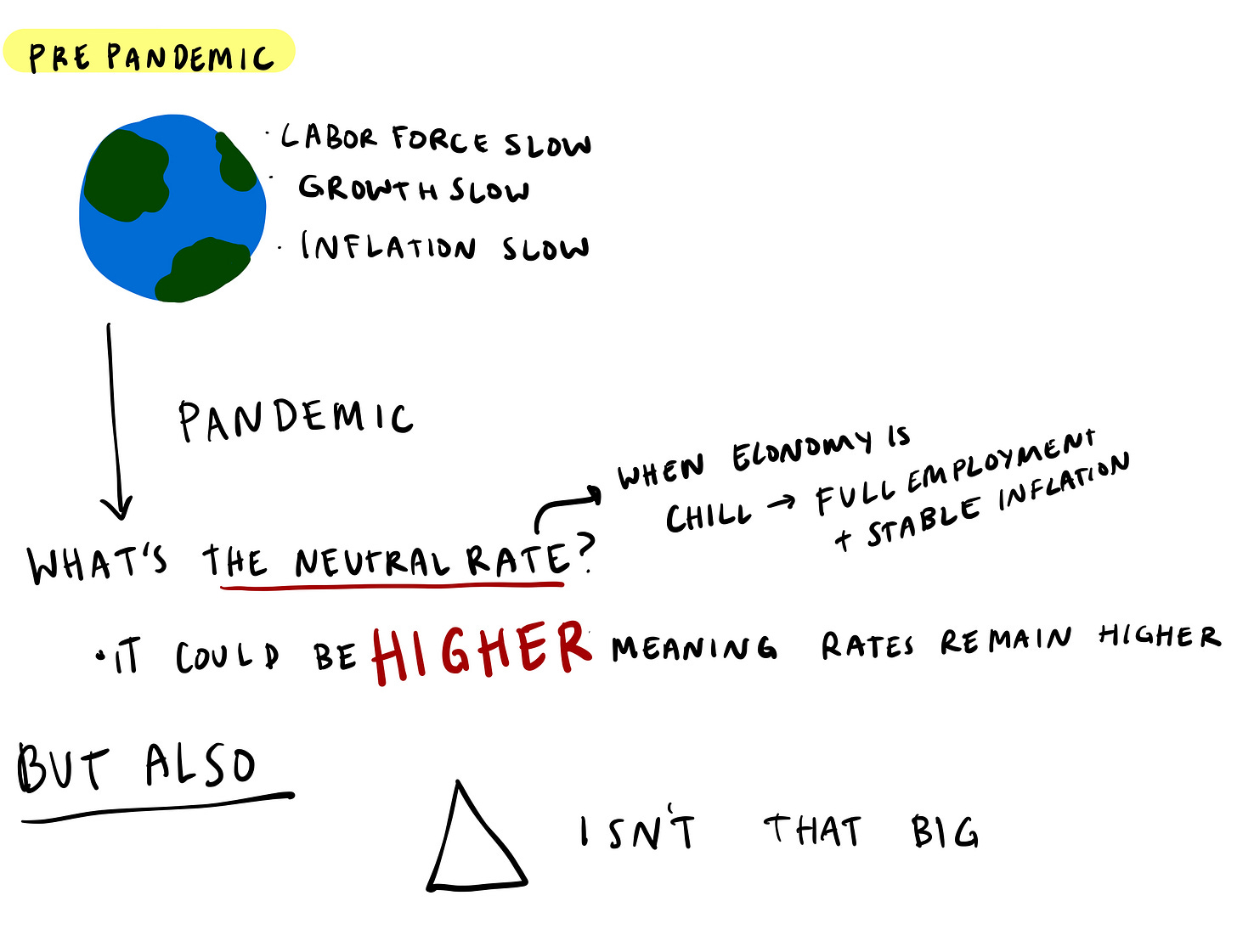

President Daly: For that I'll just talk about what we come into the pandemic with. And so prior to the pandemic, the principles we were dealing with is the neutral rate of interest when there are no shocks to the economy - everything's exactly where it should be - was very, very low. Labor force growth was very, very low, GDP growth potential was 2% or lower. And the inflation targets that all countries are setting - we're going to be fighting them from below. Inflation was too low and we're pushing it up. So that's sort of the world we came in with.

Then the pandemic hits, inflation comes to most countries, and many countries raise the policy rate just like the United States is, and now we have interest rates that are pretty high. And now the question is -and one that gets asked a lot - are we going to go back to the pre pandemic world or has this been a reset and now is the neutral rate of interest is going to be higher now? 5% is not going to be the new neutral - I mean there's no evidence that that will be the new neutral, that's still the policy rate trying to fight back at high inflation - but you absolutely could see the nominal neutral rate was 2% inflation plus 0.5% real rate, 2.5% - I completely could imagine that we go from 2.5%, anywhere between 2.5% and 3% is the nominal neutral in the go forward.

And so I think one of the lessons - I guess I'll say, Kyla - that I've taken from doing this job a long time working as an economist and in the Fed, is that every single downturn I've ever been in and every single recovery I've ever been in, people have declared that the world has fundamentally changed and nothing will ever be the way it was before. And that has never proven to be true.

What I learn each and every time is people come out of the cyclical downturn, they come into an expansion like we're in now, we fight back the inflation, people go ahead with jobs and careers, they buy homes, they have families, they invest in their communities, and yes, shocks come, but we have well oiled institutions who can deal with them.

And we go through it again. And yes, everything looks a little different, but if you step back and look, historically things are more similar than different. And we can learn lessons that help us go forward. So yes, we'll probably have new normal things, but there's no indication there'll be gigantic resets.

I mean, remember last year? Everybody said nobody's ever going to work again. Millennials are never coming back to work. Well, you know, people work. And I see labor force participation rising. And everybody's not walking off their jobs quietly quitting. We call it whatever we see today as the next thing we'll always see.

And I think we want to caution ourselves and be patient to ride this cyclical wave, get through it and recognize there's a future that has a lot of stability ahead of us.

Managing Markets vs Telling People What They Need to Hear

Kyla: Getting rid of some of that uncertainty for sure. Absolutely. You said in a recent interview that holding rates steady is policy action, that recent bond market movements could be equivalent to a rate hike, depending, and also that markets are adapting to everything. There's this thin line between, ‘disorderly and orderly pricing’. For the Fed, how do you balance managing markets? And like dealing with that side of things and then also telling people, like everyone in this room, right, what they need to hear, especially during these really uncertain times.

President Daly: I'm going to - I don't know if this is a myth you all hold or not - but I'm going to say how I do things and how I approach my work. And I'm guessing it's going to bust a couple of myths, but maybe not.

So I work for the American people. I work for each and every one of you. I get up every morning and do my job because I care about the lives and livelihoods of you and your families and everyone else who lives here in the United States and works here in the United States. That's why I'm in the central bank. We are domestically focused and we're working for all of you.

Then I watch how our policy actions, which are trying to achieve price stability, full employment and inclusive economy that works for everyone, how I watch how the economy responds to our policy actions and I watch how markets and financial markets respond to our policy actions.

So I think less about myself managing markets and more about myself collecting market information to understand our financial conditions tightening, our financial conditions loosening. Because I want to understand if, you know, the way monetary policy works is we raise the federal funds rate and then It would lower it and it would do the same thing symmetrically, but right now we're raising the federal funds rate that affects other market interest rates.

Those market interest rates affect borrowing and investment and savings and all those decisions that consumers and businesses make and then that ultimately It makes investing and purchasing less, more costly, so you pull back on that, and that slows the economy, bringing demand back in line with supply, and inflation comes down.

That's what my work is. So when I look at the markets, I'm asking several questions. Are they understanding the reaction function that the Federal Reserve has, that the FOMC has? Do they see the data the way I'm seeing it? And if not, let me learn from what they're seeing and see if it builds my understanding.

In the case recently, bond yields have tightened, meaning financial conditions have tightened. That's an indicator of financial conditions broadly have tightened. It's more expensive to get a loan. Then, well, if that's tight, maybe the Fed doesn't need to do as much. That's why I said, depending on whether it unravels or whether the momentum in the economy changes that could be equivalent to another rate hike. Well, that's data.

So I use the financial markets as data and as opposed to managing them. I'm trying to communicate to them just like I am to all of you so that they clearly understand what we're trying to achieve.

And I'm trying to see how they see things to get the intelligence that they have to ensure that I'm using all kinds of data wherever they come from to make the best decisions. Does that help? Yeah, I know. It's really, I don't know if it's busting anything. But that's how we do our work.

Measuring and Maintaining the Labor Market

Kyla: Data is always front and focus for the Fed, of course. I think one interesting part about the data that you all collect is, of course, with the labor market, right? And the labor market is really tough to measure. Like, it's pretty confusing. You know, we're seeing strength in prime age employment, the labor force participation rate, right?And the quits and hiring rates have mostly stabilized back to 2019 levels, which is all good for the longterm strength of the labor market. And one could say that the labor market is being resilient, but it's also normalizing, right? With wage growth coming back in, but also being supported by productivity gains. And a recent interview, you said there was no wage price spiral. And it seems like the risk of the Fed faces every month move more towards potentially causing unemployment versus managing inflation, right? So is there an example of these metrics that you're looking at or how do you think about balancing those two things? Fighting this big fight that you have with inflation, and then also making sure the labor market remains resilient?

President Daly: Sure, so that, that, let me just tell you how I think about the, the two mandates we have, price stability, full employment, and they're often seen. As trade-offs, right? That if you want one to be better, you have to give up the other one.

But that's not always true. And in fact, I would argue in the last nine months it really hasn't been true, right? Because inflation's been able to come down and the labor markets continue to expand. Now, what we were worried, what I was worried about, For most of the last year and a half was inflation was very far off our mark, and we needed to get traction and bringing it down as we've been able to get the policy rate up 525 basis points, and we've got inflation to start on a downward trajectory, then the risks to the economy are becoming more balanced.

The risks of under versus over tightening. But I'm still completely resolute that we've got to get inflation down in order for us to have a fully balanced economy. So then I get asked this question all the time. But what about jobs? And so I give two answers. And let me start with the first one. Because it's really relevant for right now.

The job market is continuing to expand. We need to add about 100,000 jobs a month. And we're adding far above 100,000 jobs a month. 100,000 jobs per month would just keep everything steady. Right? Because it would, it would absorb all the jobs, the new entrants to the labor force and returning people to the labor force need. We're adding far more than that, which means the labor market's very strong. So that's good news.

But let me say the other bigger thing. Ultimately, you know, I grew up in the 70s and early 80s. I came of age kind of in the 80s and get my first job. And those were the periods where we had high inflation and then we went into a terrible recession.

And what I learned from those experiences is that people need two things. They need price stability and a job. So we don't want to have people say, “well, I have a job, but inflation is running away” because what that does is it erodes real wages and people feel like they're on a treadmill.

You're making money more and more money each month and you're losing purchasing power. You're losing your place in the economy - you don't want that. But of course we don't want to raise rates so quickly or so much that we tip the economy into recession and now people have less inflation but no job.

So this is the whole balancing act we've been doing for the entire time. How much can the economy take in terms of rate increases so we can get the policy rate to a level that's reasonable to bring inflation down. And how can we do that without tipping the labor market over? I would say now the risks of how we balance those things are roughly balanced between overtightening versus undertightening. But we still have high inflation and the labor market's still strong. My concern that we're going to tip the labor market over are not as high as I'm resolute that we need to bring inflation down. Ultimately, I want people to earn a living and not feel like they are losing position every month. That's demoralizing, right? You make more and more money and you fall further and further behind. That's not the economy. That's unsustainable.

The Work of Claudia Goldin

Kyla: A recent Nobel Nobel Prize winner did a lot of work on the labor market Claudia Goldin. She did all this descriptive work. So going back through archives, compiling and correcting historical data, and it changed our understanding of women in labor markets in really fascinating ways. But there was this quote - “choices that affect entire careers are based on expectations that may later prove to be false” - so what do you think that we could change about the labor market? So this is beyond metrics and stuff but what could we do to make it more inclusive to hedge against some of these expectations that people could have going into the labor market?

So, you know, Claudia Goldin is just, if you're an economist, she's just someone you always have said, wow, that's work that's amazing because it's not just about the kinds of methods she used - going into archives, studying things - it's the topics she was willing to take on that were not considered like the mainstream topics you should take on. And what they've done, it's transformed how we think about the labor markets, transformed how we think about education and, and how we look at history and think about these things.

And one of the lessons from that is if we expect people to be a certain thing and then they make choices based on those expectations and then we later prove them to be wrong What's the big lesson there, in my judgment? We've left so much talent on the table. So, your question is what we can change in the labor market.

Let me start earlier. What can we change in how people expect themselves to be when they grow up? If someone comes to you, I mean, you're young and you're gonna say “I can't really affect people.”

You can affect people at any point in time. Because they may see their world like this. And what you're saying is, “oh, it could be like this.” I mean, you can go from being an options trader to interviewing a bank president and having your own following. And those are things that are about transforming people. So I think that's what the labor market has to learn that how you start out. It doesn't need to be how you end.

You can have a dynamic career. You can reinvent yourself countless times. You can reinvent yourself at the same, in the same occupation or job or even place, but you can do different things. And I think the labor market sort of looks for lots of experience and what I see happening, which is great. It's one of the benefits of a tight labor market.

People are looking at skills and skills that you might gain in one profession you can move those skills to another profession. And I think that personally, I've studied the labor market a long time. Not only does that release the talent that's always been there, but it actually probably is the new frontier because if you take somebody from one profession and you say, “oh, reinvent yourself and come over to this other profession, but bring all the skills you've learned in that job.”

That is the newest way to create innovation and ideas. I have reinvented myself so many times in my career even in the same profession, just by saying, I'm interested in that. I'm going to go work with people who are interested in that. I've worked with psychologists and demographers and other social scientists, sociologists, I've worked with a physicist at one point, and all of that made my mind expand. So I think the labor market should be this sea of talent, where everybody gets, gets up and says, I can do that, and we see what happens. But I think, you know, tight labor markets are good for this. People complain about tight labor markets, not workers so much, but one of the things that constraints do - tight labor markets - is it creates innovation. And I think this opportunity is to take what Claudia Goldin taught us and realize. We have lots of opportunity here in the U. S. (and other places) but here in the U.S. and we should take a hard look at it.

The loss of beginner mode

Kyla: Yeah, absolutely. There's some aspects of the economy that aren't, that don't have as much opportunity, right? So it feels like the beginner mode of life is gone. So the Mitsubishi Mirage, which is like I think the last car that was selling for under $20K - they're discontinuing it. And so now I don't think there's any cars for selling that are selling less than $20K. And so what would you say to this idea that it feels like there isn't accessibility in the beginning of life? Like it's really hard to get a house, cars are very, very expensive - what would you say to young people who are grappling with that?

So every generation is going to have some challenge that seems different than the generation right before it. That's just the way it goes right? That this generation comes in and you could face the financial crisis, you could have seen your parents in the financial crisis, then we have a pandemic, now we have high inflation. When I came it out of school and I started entering college and going into the labor market. It was high inflation and a very poor job market and we were in a major recession. What I learned from that is to take the moment in and get through it, but not lose hope for the next time. So I said, “well, what do I want to be? How do I want to be in the world? What do I want to do?” So I had, as many of us do, you buy your first car as used because you can't afford the new one. And you just work your way up, and if a new car is what you want, you eventually get one. But you don't have to have it today. The same thing with a house. You might say, “Well, I can't buy a house right now, Mary. But I want one.” Well, then start thinking about how to save and work on that so that when you, when interest rates come down and you're ready, you can get in there and get it. But it doesn't mean your life is stalled out. Right. It just means you're working on that.

And I think ultimately, what I say is this economy right now is imbalanced. That's why we have high inflation. We're working hard at the Fed to make sure it comes back into balance when things are more in balance, when inflation is 2%, and the economy is growing in a regular way. All the decisions you're forced to make seem more manageable and right now that we have all those pressures - you're trying to keep up, inflation's coming up, it's hard to buy a house, it's hard to buy a car, etc.

Everything seems just like it'll always last and it won't always last. That's the benefit of living a long time. You've seen everything once or twice before and you realize it comes and it goes and the people who prepare themselves while it's there to grab it when we're out of it. Are the people who are in the best position.

So ready yourselves for when interest rates go down, for when the economy comes back into balance. Get yourselves ready to go and then go forward. It's a good opportunity, right when we emerge from a transition and we're emerging from the transition. That's the other piece of good news.

Inflation is coming down. Interest rate raising is working. The economy is coming back into balance after the pandemic, and ultimately supply and demand will equalize and it will get easier.

How does the Fed think about geopolitical risk?

Kyla: And I want to zoom out to the super big picture. There is a lot of geopolitical unrest, which is a very reductive summary of what's going on. But how does the Federal Reserve incorporate that into their worldview in the policy actions?

President Daly: When you think about things like wars and the outbreak of war, well the first thing that happens, and I think this is true for all of us, is we just recognize the human toll. And it's got to be first and foremost to take on the human toll of things tragic like wars.

What we then, of course, do - because our role is about the domestic economy and price stability and economic growth and full employment - is we think about what is this doing to our growth, and if not to our growth, to uncertainty. And so, right now, geopolitical uncertainty is adding to already some domestic uncertainty and some uncertainty about what does it hold and how fast will it come.

And that is just something that makes people a little more cautious. When uncertainty rises, businesses are a little more cautious about hiring. Building out output. Consumers become a little more cautious about spending because they want to be ready for whatever it is. But that's how I factor it in.

And then, of course, if it changes oil prices or it changes demand for exports or something, we would monitor that. It's just the data that comes in. So it's not that we rotate everything to that, but we absolutely pay attention to it, but it's part of a large dashboard of data that we're always following.

I gave a talk last week, a speech in New York, and I used two words - vigilance and agility. So we need to be vigilant to keep watching the data, constantly looking at the dashboard of indicators, out in our communities, talking to people, talking to people like yourself, thinking about these things.

And then we need to be agile enough to adjust policy so that when conditions change, we can change. Because if we get stuck and we're only doing one thing, and we're not vigilant at watching the data and agile and adjusting how we see the world, well then we can end up with policy mistakes. And so, that's why you hear us say we're data dependent.

If I unpack data dependence, it's really vigilance and agility. Those are the two things that we're bringing to the table when we deliberate and debate what to do next. Just to reinforce this always with the mind that we're serving all of you and our goals are given and they're simple - price stability and full employment. There'll be a quiz later.

What have you disagreed with that you’ve changed your mind on?

Kyla: So your 2019 Syracuse commencement address - you mentioned that your favorite policymaking space are those that disagree with you or that you disagree with. I'm not gonna ask you who you disagree with. But what are some things that you have disagreed with recently that you've come to change your mind on?

That's a terrific question. And wow, I love it when people read stuff back to me that I didn't expect. Okay. But seriously, you know, you said something, you won't ask me who I disagree with.

Really the best part of your life can be this and best part of policymaking, best part of having people surround you. It won't be you always disagree with this person. It will be different people take up a different stance and argue it. That's when it really is working, right? It's not that you just disagree with this person because you have a different value system or whatever. It's that different people take up, they just see the world differently and then they think about it.

So here's an example. I was a great champion of labor force participation could absolutely go up during after the financial crisis when people said, No, it's going to be stuck where it was right after the financial crisis.

And I was one of the people pushing it. Interestingly, after the pandemic, I did get worried that we were just going to see it not come back. And that because of the problems with child care because of the problems with commuting distances and gas prices and things we would just see that stalling out and I have a couple of younger team members working on this topic and they, they revitalized my old, some of my old work and reminded me and said, no, I think if you do it this way, you can see something positive.

And I was like, “I don't think so.” Sure enough, they're right. And I changed my mind. They disagreed with me, not by just by saying well, I don't agree. They brought me evidence and they said, “okay here's what would need to happen if we're going to see this rise.” And so then I said, “well, what are we going to watch?”

Well, we're going to watch what happens to female labor force participation, we're going to find out what happens to younger people's labor force participation, we're going to find out what happens when the dust settles and the pandemic settles down and people go back to work. They took me through all their information, and that disagreement did two things.

One, it proved to be right, but that's actually not the most important thing. The most important thing is it made me less sure of what my prior was. And that made me say, if you go back to my public commentary, you'll notice this - that we actually don't know what's going to happen with participation.

Because I came in thinking I'm not as optimistic, but their evidence and their risk assessment cautioned me from being declarative. And I think that's what's really great about policy. Yes, let's be declarative about things we know, but let's also be very humble about when we don't know and just communicate effectively that we're watching it, but we don't yet know. And the data will guide us. And that's what makes good policy. Letting the data guide us. Absolutely.

Final Thoughts

I really enjoyed this conversation, and there were several questions that I didn’t get to ask that I will leave here, as open-ended

A lot of people say that the Fed’s tools have contributed to inequality or have ‘unintended consequences’ - and obviously, a lot of that is outside the scope of the Fed because you have one tool, and its a blunt one. But we focus so much on inflation that sometimes employment feels tossed to the side - but you began as a labor market economist, are a labor market economist - do you feel like maximum employment, and the Fed’s path towards that, are doing work to reduce inequality / manage it?

In the NFIB Small Business optimism survey there is big gap between hard and soft data. The vibes are off. Someone said that ‘small businesses need to stay angry to fight inflation’ - how important do you think managing emotions are to managing the economy?

Joe Weisenthal of Bloomberg said “That to advance technologically, you need more people doing the doing” - the Fed has this mandate of price stability and maximum employment right, but how do you balance the idea of progress, especially in a potentially stagnant world, with the mandate? Is there ever a moment where you revisit the priors?

So much of core services ex-housing is really goods sensitive, not the labor market (so jet fuel is a function of demand of air travel, etc) - how does the Fed think about those intricacies?

Can you walk through Moonstone and Silvergate and the dynamic of Fed regulation relative to banks?

Media is increasingly negative. How does the Fed think about the wall that faces the American public in how they get their news? Is there a goal to combat this negativity, since messaging and Fedspeak are so important?

Thanks for reading.

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice or recommendation for any investment. The Content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, or financial advice.

Just a quick note to agree with Nick E: phenomenal interview, super informative and helpful. You are one of my idols--that gift of explaining very complex issues in a way that is really accessible to the rest of us, non-economists--but I have to say I’m also super impressed with President Daly. The interview on YouTube was a pleasure to watch. Many thanks to both of you!

Just excellent Kyla. And President Daly is a star ✨. 🙏🏽