This was a long time coming. Thank you to everyone who listened to me chatter on about the limits of language and allowed me to draw diagrams on restaurant napkins to try and get just a bit closer to whatever the ending of this was - if there is even an ending at all. With that being said, this piece will likely be cut off in your inbox

Words, Language, Narrative, and Trust

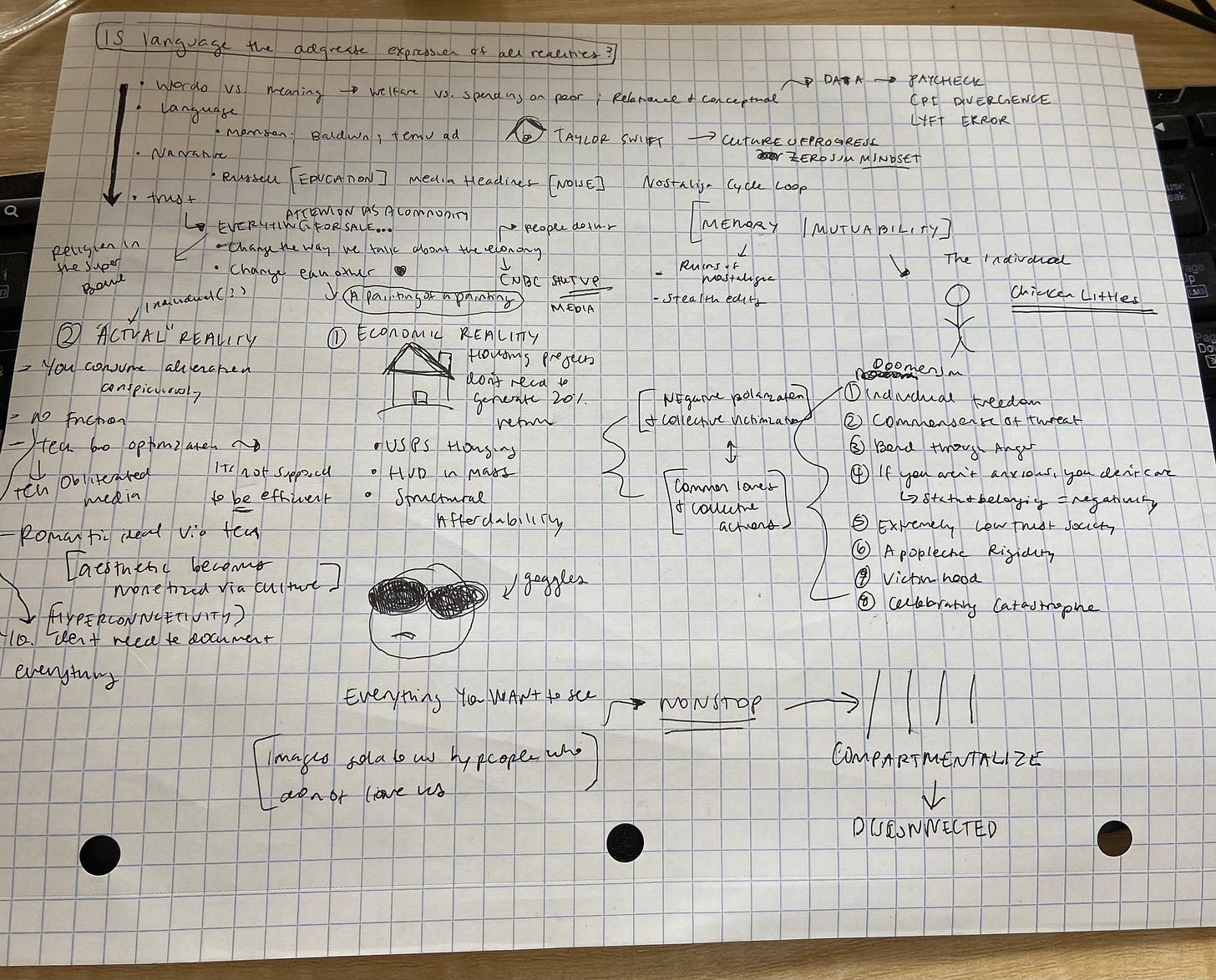

“Is language the adequate expression of all realities?” the (oft-quoted) Friedrich Nietzsche asked when discussing what truth and knowledge really mean - and how language limits us in the quest for both. I have been obsessed with both language and reality for the past several months, especially in the context of how we talk about the economy.

Anna Deavere Smith wrote about this concept (in a more tangible, not so Nietzsche way) in her book Talk to Me - the idea that language is abstract, it doesn’t mean what we want it to mean, and that creates this fraying of the community fabric.

Who’s listening anymore? What does it take to get people to listen? When do people feel they need to listen? When do they feel they have to listen? … We get so used to hearing things that they have no meaning… We live with the expectation that words mean very little, because we have seen it all before, heard it all before.

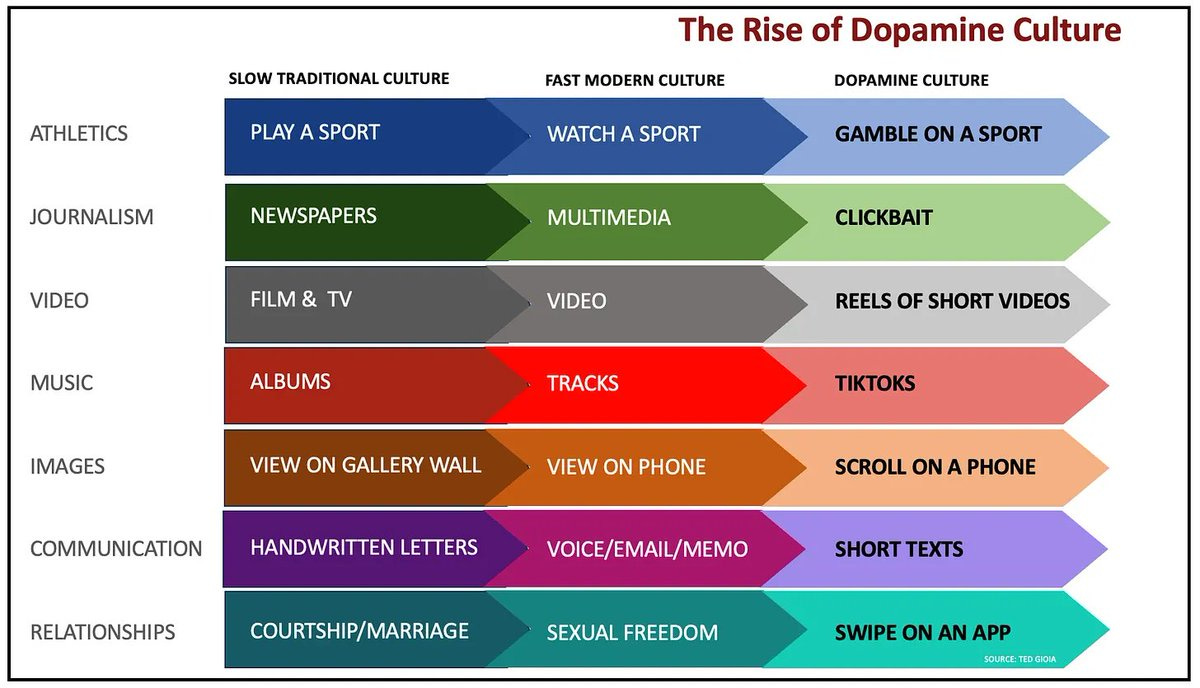

So many words, yet many things lost. “The fastest growing sector of the culture economy is distraction… But it’s not art or entertainment, just ceaseless activity” as Ted Goia described it.

More simply, this.

We are saying everything, but also saying nothing at all. How do we fix that?

Words are a way to confer meaning that often gets separated from the concept the word represents until we are just sort of talking at each other about things like “rizz” and “Price-to-Earnings Ratio”. Language is failing us. Narratives are collapsing, stagnating, insert-scary-adverb-adjective-here.

I’ve written before on the limits of language, but in this piece I want to discuss the forces of education, media, and the nostalgia cycle loop, focusing specifically on the attention economy and how the failure of language has impacted how we understand the economy and each other, ultimately eroding trust, the most expensive commodity in the world right now.

So first, words.

When the Words Don’t Mean What We Think They Do

We speak to one another using words that have evolved over and through time, so that we know what one is talking about when they reference a doorknob or a pencil. As Toni Morrison stated in her 1993 Nobel Lecture -

“We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.”

But we are shrinking away from language as a whole. Whether it be things like “TikTok speak” where you are forced to speak in short snippers to catch those gleaming droplets of attention or memes, which support the idea that pictures are indeed a thousand words, we are losing something in between the word and the meaning of the word.

Paycheck to Paycheck

Even the vocabulary that we do use is limiting. This is where the battle between words and concepts plays out. The number of Americans that support ‘spending on the poor’ is 71%, but if you call it ‘welfare’ that number drops to 30%. There is no difference beyond that of words! Yet that makes all the difference.

There is a tension between definer and definition which also creates a phenomenon where the words we say no longer mean what we think they do, especially regarding the economy. For example, we have three different definitions of what it means to live “paycheck to paycheck”

A family is struggling to make ends meet, and would be unable to finance normal expenses like rent and groceries.

The lack of a substantial saving buffer.

Not having money left over AFTER having contributed to savings.

And of course, news sites will blast the below statements - and so if you read the news and see this, of course you're going to be freaked out. By words. Not meaning what we think they mean.

And it’s a nightmare! Because if you dig into this data, as Matt Darling painstakingly does about once a week on Twitter, you’ll find that -

The median American household has a net worth of $193k

They have $8k in checking/savings

54% of adults have 3 months of expenses saved.

And if you go even deeper, the creator of the paycheck-to-paycheck number is suspect. The financial services company that publishes the paycheck-to-paycheck statistic refuses to share the text (read: the WORDS) of the question they ask to get to their “60% of Americans live Paycheck-to-Paycheck" metric.

So we have this number that no one knows where it’s coming from, yet we are using it to make informed decisions on headline text which informs what is happening in the economy - but also informs how people should feel about what is happening in the economy. No wonder the sentiment is off! No wonder people are confused! It’s hard to understand what’s happening, and that makes all of this so much harder.

I mean just look at GDP and GDP headlines. It clearly doesn’t really capture happiness or whatever, but it does capture consumer spending. Is that the same thing? Is a growing economy happiness, numerically speaking?

And then the interpretation gets confusing.

People think that inflation going down means that prices should be going down - but that’s not what inflation going down means. That’s deflation. But what’s deflation? What do you mean prices going down is a bad thing? It’s a whole giant confusing mess.

What sort of data do we need to understand the economy better and how can we make that data as understandable as possible? And then, what would it look like when people do understand the economy? How can we help people make better decisions?

The Data is a Mystery

It’s not just words, it’s actual data points too. The CPI print that we got last Tuesday was high, and there was a gap between the two rent measurements, rent of primary residence and owners’ equivalent rents. No one really knows why it happened!

Even the Council of Economic Advisers was like “huh that’s weird” but then of course, some of the weirdness was the “January Effect” or firms raising their prices, which rocks. As Jonathan Levin at Bloomberg Opinion summarized

“Long story short: data works in mysterious ways on a month-to-month basis”

Economic and financial data doesn’t always do a great job of telling us what’s going on. Whether that be because people aren’t responding to surveys like they used to, or quirks that are hard to explain, or simply having a typo in your earnings (like Lyft accidentally adding an extra zero to their margins which caused their stock to rocket 60% because people thought they were going to have 500 basis points of margin expansion - not 50 basis points, which is what they meant to say) - the data and the words create realities that don’t really exist - until they do.

Which gets into the limits of language.

The Alphabet Soup of It All

The problem with the economy is that it’s not doing that badly.

But the other problem with the economy is that economic metrics do a poor job at capturing and explaining what they are meant to capture and explain (I will say this too many times, my apologies)

So we end up in this weird loop of

“actually the job openings number isn’t really that good as an indicator of the health of the labor market but that’s what the Fed looks at so that’s what we have to look at even though it doesn’t really mean what we think it means”

And of course, we look at more than just one metric to figure out what’s going on in the economy. The alphabet soup of numbers and data and figures eventually come together to create a reflective surface that reads “economy good” or “economy bad”. Like this -

But like to be very clear, Bloomberg Surveilliance published a piece stating “If You’re Not Confused, You’re Not Paying Attention” - hence why the economy feels good and bad and everything else. But the current reflective surface does reveal mostly (?) good metrics -

Almost six in ten workers are getting raises larger than inflation.

63% of Americans rate their current financial situation as being "good” and feel largely decent about their lives.

Homeownership for Millennials rose to 55%.

Import volumes have returned to normal.

New business creation is on a major upturn.

We had the strongest inflation-adjusted wage growth in 50 years.

But these metrics don’t convey the entire story. Of course not! Alphabet soup.

We have a structural affordability crisis, and because we are in a ‘new normal’, things like the housing crisis can’t hide and neither can anything else. As Henry Hill wrote about the fiscal austerity and the lessons learned post-ZIRP:

The end of zero interest rates means that long-running problems such as the housing crisis and stagnant real wage growth can no longer be disguised by cheap credit. The decision to take the tactically-easier path of salami-slicing austerity instead of actually designing a smaller state means government is big as ever, but nothing works.

This leads to the disconnect between consumer sentiment and economic data, a concept I have written at great lengths about. And the language that shapes sentiment via the interpretation of the data is the culprit here.

The words we are using kinda suck.

I had the chance to talk with John Burn-Murdoch at the Financial Times about this idea of language and how it shapes progress. His piece “Is the west talking itself into decline?” analyzes how language can do a lot in shaping our economic reality - and he highlighted that the words that we use are no longer positive and focused on growth, but rather they are fearful and focused on worry.

Progress can come from many different ways, but one that is often overlooked is the role of culture and language

And there are huge consequences - like creating a zero sum mindset and a turn towards stagnation and populism. This also leads us to what researchers are calling the “Need for Chaos”. As Derek Thompson summarizes, it’s

“Status-anxious people who feel marginalized in relatively rich countries, like the US, are more likely to engage with politics as a kind of game: feel empowered by sowing chaos.”

If you’re not feeling anxious, it means you don’t care. If your words aren’t ones of malaise and foreboding, you aren’t paying attention - which like, to be fair, isn’t totally wrong! The things to be anxious about are numerous. The geopolitical warfare. The walls of any sense of structural affordability caving in. The endless political theatrics.

But yet.

As Marilynne Robinson when asked why we don’t recognize goodness -

[...] It’s as if we’re all supposed to be cynical, even though, as you say, many of us have excellent grounds not to be cynical at all. It’s a mannerism; it’s a pose. It’s perhaps more characteristic of privileged people than of people who really might wonder about justice and mercy. It’s terrible to say that a great civilization could collapse from the force of a fad, but sometimes I feel as if that’s what’s happening.

This is a problem! So we’re using bummer words, looking at each other with eyebrows raised, feeling like only one of us can win, and then also trying to sow seeds of hell into our already wilting communal garden or whatever. Jamie Dimon was at Davos, the Burning Man for Big Business, and said the following on Trump:

"I don't like how Trump said things, but he wasn't wrong about those critical issues. That's why they're voting for him. People should be more respectful of our fellow citizens. I think this negative talk about MAGA will hurt Biden's campaign."

Dimon has been wrong a lot. Everyone is wrong a lot. But part of what he was saying was that the language we are using to talk about politics, to talk to each other, is not… right. The Biden administration is not truly listening to the concerns of the MAGA (not going to debate that, but the idea is that no one is really listening to anyone, just hearing).

And this is part of the lack of language to describe the state of politics, the weirdness of it all, etc. We have no relational words for what we are going through. Jay Rosen, a journalism professor at NYU, wrote

“The internet is rewiring not only the media sector (as with streaming) but the public itself, which is breaking up, or being broken, into multiple — some say parallel — realities. As you can tell from my attempt to describe it, we do not have a good language for this shift.”

The words aren’t working. Everything requires some element of context that has gotten completely erased in the layers of meta-irony that we interact with when we talk about things like ‘living paycheck to paycheck’ - it creates a fractured reality.

Not only are we not seeing each other, we aren’t even on the same plane of existence.

Oh, the clickbait

As everyone knows, media headlines are impossibly negative, a constant thrum that hacks into our consciousness and is essentially impossible to escape. The sauce SELLS. And the more clicks, the more money, blah blah, we all know this.

It’s the crowing of media headlines such as this one from CNBC that happened as Helene Meisler describes “we rally 5% in a straight line and we get one 1% down day and the banner is gigantic as if the markets have been heading down for weeks”.

This is the business model of the news, right? It’s profitable for people to ‘eat bad news for breakfast’. As Jared Bernstein, the Chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers said

In particular, respondents had been less likely since 2022 to hear good employment news than pre-pandemic, even controlling for the strength of the labor market. January’s preliminary data are closer in line to the pre-pandemic relationship between jobs growth and news

It’s similar to how the media covers Trump versus Biden because Trump is not boring. Bad news is not boring ! Good news is boring! So, naturally, people are hearing bad news! All of the time! Of course they are going to feel bad!

The Discount Retailer is Religion

It’s even (especially!) in the Super Bowl commercials. Temu spent $21 million dollars on their little SuperBowl commercial advertising the idea “Shop Like a Billionaire”.

For context, Temu is one of many discount retailers out of China sweeping the globe selling things such as a hammock for cats, a watermelon slicer that looks like a medieval torture device, USB powered mini desk vacuums or levitating plant pots for like $3. Their primary audience is the Gen X / Boomer world which makes sense as they spent $1.2b on Meta advertising in 2023. But they gamify the shopping experience with roulette wheels and absurd discounts and all the while, they promise, that you can Shop Like a Billionaire.

The language of that through the lens of a perfect model of overconsumption calls into question the price of pleasure and the cost of convenience.

What does shopping like a billionaire really mean?

Temu is a mirror reflecting our deepest desires in the digital age, consuming to feel. But the most upsetting thing about the slogan is the truth of it. Everyone wants to be a billionaire - perhaps because they want to spend money incessantly - but mostly for the safety of it.

That’s why it was sort of funny that another big spender at the Super Bowl was… religion. One commercial (funded by Hobby Lobby) was titled ‘He Gets Us’ and another was for Hallow, a Christian prayer app backed by a16z.

There are similarities between Temu and the ads for faith, specifically through the lens of language. The Temu ad, which artificially promises safety and belonging via spending money on drop-shipped plastic items ripped from Amazon storefronts, is offering the same things that the religion commercials are (albeit in completely different ways).

Both say ‘come here and be okay’.

Consumerism is a religion in the sense of salvation in the form of momentary reprieve. One must say confessions at the altar of fast fashion. The average SHEIN shopper is a 35-year old woman who “cares about sustainability”. What!

What does that MEAN. What does sustainability mean? What is the expectation set? What are the expectations that we have for ourselves?

All of this is on the basis of experience. The language shapes how we interact with the world, but it’s our responsibility to shape our own language, as James Baldwin discusses “it is experience which shapes a language; and it is language which controls an experience”

Which gets us into narrative.

When You Tell a Story, Who is Listening?

So words shape language, and language shapes narrative. But as Jeanette Winterson wrote in Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? -

“Stories are compensatory. The world is unfair, unjust, unknowable, out of control.” which makes the stories all that more important… When we tell a story we exercise control, but in such a way as to leave a gap, an opening. It is a version, but never the final one. And perhaps we hope that the silences will be heard by someone else, and the story can continue, can be retold.When we write we offer the silence as much as the story. Words are the part of silence that can be spoken.”

Part of the problem, a complement to language if you will, is that there is no more silence, or at least, it’s harder to find. And the silence is where the growth exists, when the noise stops and the iteration towards finality is filled with gaps and the gaps are smaller and smaller because there is more and more to distract.

And this is because of the dopamine hits of social media, something that is likely never going to go away but will probably need to be managed. It’s how social media wants you to feel anxious and gives you the tools to feel anxious, because if you’re freaking out, it means you care, right? So freak out.

Freak out more. The normal things you do? It’s actually a sign of something wrong with you. You’re a mess. You’re a mess! Give me your data give me your money give me your time give me all of you and scroll and swipe and scroll and swipe andscrollandswipeandscroll. And scroll. And scroll. Consume. Consume. Consume. Forget context. As Julia Alexander wrote “I see, I engage, I disassociate”

This is the backdrop of the whole phone as an extension of arm thing. The way that we experience time is completely warped now. Time has been compressed to the past and present and future all at once as we interact with everything all of the time across every time period, as Douglas Rushkoff discusses in his (very good book!) Present Shock.

Rushkoff argues that everything is moving on a fashion timescale now. Everything is fast, quick to the point of a paralyzing state of mind. Intelligence is equated to speed, especially in the digital age, but we lose some things in the speed of it all. The difference between information and knowledge is gray.

Time is flat. There has never been more of it, but we have never been so busy. But we are busy with noise, moving along a timescale that is maybe just a little too fast!! Rushkoff argues that we have experienced narrative collapse.

But I don’t know if it’s so much narrative collapse as much as narrative stagnation.

As Marcel Proust wrote in Time Regained

“Indeed nothing is more painful than this contrast between the mutability of people and the fixity of memory.”

And that’s sort of where we are - we cannot escape anything, therefore we must live in everything. We have this weird balance of existing in memory palaces that are inescapable (not a bad thing!) due to social media, as well as trying to figure out what exactly the capital-I-Individual is meant to be doing here.

Donna Stonecipher wrote the beautiful poem, the Ruins of Nostalgia, which captures the memory part of our personhood (I won’t include the whole poem here, but it’s shockingly gorgeous) -

[...] The barber is dead; long live the barber. The city of our youth no longer exists; it exists in our minds. The barber's pinup calendars are smoldering their way down the landfill. Johannes Hofer believed that nostalgia could be cured with opium, leeches, or a trip to the Alps, but we know that the only cure for nostalgia is nostalgia [...]

I’ve discussed the nostalgia cycle loop before, and how we just tell the same stories again and again. Marvel cinematic universe.

Existing in the past is easier than engaging in the present.

But what happens when the past is not the past? As T. Becket Adams highlighted, Alicia Keys hit a sour note in her live Super Bowl appearance (it happens! It’s okay!) but it was edited out of the official YouTube page! He writes -

For all the recent discussion re: the post-truth world, we need to talk more about what record-keeping should look like in the Internet era. Because things like this audio swap – with no explanation or heads up given – is crazy-making. How are we ever supposed to return to something approximating a consensual reality when even the trivial things we experience as a nation undergo stealth edits?

So what I am saying here is that time is weird. It doesn’t work like it used to. And because time is weird, we are haunted by our memories. Everything is everywhere all of the time. So we end up craving the past - but the past, due to changes in technology, is now malleable. And that fractures our reality even more.

And finally, finally, finally, this gets into the trust part of this rambling essay.

A Nation With Commitment Issues

So there is a very brilliant article in the Atlantic titled Chicken Littles are Ruining America that touches on a lot of themes - the rise of individualism, how we like to bond through anger and a common sense of threat, how status and belonging are conferred through negativity, and “apoplectic rigidity” which is “an inability to see the world as it is, but rather only those nightmarish elements that justify the hatred and rage that are the source of your self-worth.”

Like what a kicker of a line! The article discusses the victimhood complex and the celebration of catastrophe and how all of this has led to negative polarization and collective victimization. And this sign from Mister Bagel summarizes it well -

But this is for a reason!

The Atlantic article essentially says “listen, everyone is collectively freaking out and it’s for a lot of complex reasons, but the main thing is doomerism is a salve in the face of everything we are dealing with.” I’ve written on this before, the promise of saying the world is going to end is entertaining, its community, it answers the siren call of the leadership crisis.

But… why is it happening? I think it’s for three main reasons.

One part is the Kafka quote - “you are free and that is why you are lost”.

The second part is we live in an economic reality (she returns to it, finally!) We have a structural affordability crisis. There really isn’t a beginner mode - with the Mitshubishi Mirage no longer being sold, there is no car for sale under $20k. We are all very aware of what’s going on with the housing market. There are rolling recessions that are impacting employment, as well as "restructuring” which suggests more frictional than cyclical unemployment. The stock market is based solely on NVDA. Food is taking up more of our income. Borrowing costs are high.

But.

Parts of this are improving.

With the housing crisis, we are finally realizing that maybe housing projects don’t need to generate 20% returns and the government can take part in some of the bidding process, as shown in Montgomery County, Maryland.

Housing is the root of a lot of the anger that threads itself through our economy (as well as decades of stagnant wages, rampant inflation, etc) but it’s becoming harder and harder to take chances (whether that be innovation, risking it all to move to a new city, trying something new in general) because it’s becoming more and more expensive to do so.

Then there is third part, the other part of the economic reality, the attention economy, in which our eyeballs are very expensive commodities. We have commoditized ourselves to the point where we sort of are what we consume. We’ve assetized our feelings too to give them “value” on a sociological marketplace. Of course we don’t trust.

It doesn’t help that we are using language to come up with words like “doom spending” (the idea that “it’s just easier to spend money on things that will bring you immediate fulfillment”) or things like quiet quitting which shapes the narrative in a weird way because like hello? What does that mean?

But it’s deeper than that.

It’s the teens being told to become specialists by the age of 18 so they can be cookie cutter perfect for college.

It’s the cars becoming monochromatic. Safety is found in standardization.

It is adjacent to the hyperoptimization required to exist in some elements of the digital world, as Rebcecca Jennings explored in Everyone’s a Sellout Now. She writes

“The commodification of the self is now seen as the only route to any kind of economic security.”

Appease the algorithm - if you don’t? Good luck out there.

When you’re constantly being sold to, when everything is a Temu ad all of the time, you get to another part of the Chicken Little essay - you stop trusting anything. The U.S. is a very low trust society, a bunch of eyebrows raised at one another in a skepticism which has MADE us stop hanging out with each other.

And this gets into the final part - we just don’t see each other anymore. The whole loneliness crisis thing. As Rushkoff wrote in Present Shock

“In the real world, 94 percent of our communication occurs nonverbally. Our gestures, tone of voice, facial expressions, and even the size of our irises at any given moment tell the other person much more than our words do… Without such organic cues, we try to rely on the re-Tweets and likes we get—even though we have not evolved over hundreds of millennia to respond to those symbols the same way. So, again, we are subjected to the cognitive dissonance between what we are being told and what we are feeling. It just doesn’t register in the same way. We fall out of sync.”

Compartmentalizing everything in the attempt to manage it all makes it all feel even weirder.

The Apple Vision Pro goggles and the Meta goggles are making it all weirder. The last thing we (probably) need is another piece of technology that disconnects us more. And with all things, some parts of the goggles are good - it will be a game changer for those with mobility issues and disabilities.

But it feeds into our collective isolation.

It’s a “lonely experience” and of course, there are philosophical musings that speak for themselves. Guy Debord wrote “this society which eliminates geographical distance reproduces distance internally as spectacular separation” and Jacob Needleman in Time and the Soul -

"The essential element to recognize is how much of what we call “progress” is accompanied by and measured by the fact that human beings need less and less conscious attention to perform their activities and lead their lives. The real power of the faculty of attention… is one of the indispensable and most central measures of humanness."

We are what we pay attention to. And one of the worries with the goggles is that we become more hyper-fragmented, more sucked away into our spaces, seeing only what we want to see - removing all friction. And already, the removal of friction is the root cause of the loneliness crisis.

On the Power of Friction

Rosie Spinks wrote a wonderful article titled The friendship problem on why friendship feels like admin now and she quotes Esther Perel

“Modern loneliness masks itself as hyper connectivity. And so people have easily 1000 virtual friends, but no one they can ask to feed their cat. That loneliness, which is really a depletion of the social capital, is extremely powerful. […]

Everything about predictive technologies is basically giving us a form of assisted living. You get it all served in uncomplicated, lack of friction, no obstacles and you no longer know how to deal with people. Because people are complex systems. Relationships, friendships are complex systems. They often demand that they hold two sides of an equation. And not that you solve little problems with technical solutions. And that is intrinsic to modern loneliness.”

Everything has been optimized to the point of near nonuse - including friendships. The commodification of self contributes to that, tech as a forcing function to “create aesthetics, define culture, monetize people”. As Jon Haidt wrote on the insistent digital need - “the proliferation of smartphones and social media mean that young men and women now increasingly inhabit separate spaces and experience separate cultures.”

So we seek out the scroll, while dealing with a true, often frightening economic reality and then also exacerbating some elements of reality to create a sense of friction. Loneliness. We hyperconnect to the point of disconnection.

Okay?

David Brooks ended his Chicken Little piece calling for common love and collective action, which is sort of all you can do with this? This stuff isn’t easy. One could say “well log off, you clearly need to” but that leads to this absolute loop in which even we escape the void, it still beckons to us. As Chris Said wrote on social media’s trap and inferior equilibrium -

"Because social media is where all their friends are, most teens have no choice but to use it... Meanwhile, a minority of teens do not use it, but they are also unhappy because they miss out... Everyone is therefore less happy."

Timothy Roy argues that the solution is finding true community through gathering those that build community, rather than trying to separate amongst “ethical or relationship or financial or fitness system”. Being near each other. Allowing friction. Knowing friction comes with failure.

A large part of looking forward might be recognizing our connections, as Adrienne Rich in On Lies Secrets and Silence

There is no “the truth,” “a truth” — truth is not one thing, or even a system. It is an increasing complexity. The pattern of the carpet is a surface. When we look closely, or when we become weavers, we learn of the tiny multiple threads unseen in the overall pattern, the knots on the underside of the carpet.

I think the biggest thing is changing the way we talk about the economy, too. You can’t have an asterisk next to everything saying *this might not apply to your individual situation, which is challenging in the age of the for-you-page. But it comes with giving people context. Not scaring them with headlines. Explaining what things mean, simply.

There has been a lot done to recognize the structural issues of affordability, but policy will increasingly need to move in that direction (and it has! progress!!). But we also need to be mindful of the way we consume financial information - and that at the end of the day, headlines are a business model.

I always struggle with ending pieces because I really do not like being prescriptive. I much prefer the warm cocoon of descriptive. The words sometimes aren’t enough.

There was a tweet that said “cultivating ease, joy and fun is, to my utter surprise, one of the highest roi skills” - and that’s a big thing. That’s a big thing. Being around one another in a meaningful way. Sharing things. Sharing in each others stories in a real way. Recognizing that language is sometimes not enough - and that trust might be formed through just being around one another more.

Sean Thomas Dougherty says it better than I can-

Thank you for being here.

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice or recommendation for any investment. The Content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.

Kyla, thank you for this piece! The way you boil down all the complexities affecting society, how it compares & contrasts how these complexities were in the past, and how you weave together the thoughts & ideas of other brilliant people and data is awe-inspiring. I feel inspired to focus on physically being around people and forming connections, or at least being a person that can "cultivate ease, joy & fun" by meaningfully being with people.

absolute banger, thanks for writing this