We can’t talk about building more homes without talking about home insurance. Also, an update to the American Dream risk model.

Housing Policy

Kamala Harris released her economic proposals to an array of pushback1 and support2. For both candidates, it’s all sentiment and messaging - vibes, some might say. But, she also announced some concrete policies around housing, including:

The construction of 3 million new housing units over 4 years

Up to $25,000 in down-payment support for first-time homebuyers.3

A $10,000 tax credit for first-time homebuyers.

Tax incentives for builders that build starter homes sold to first-time buyers and for building affordable rental housing.

A new $40 billion innovation fund to spur innovative housing construction.

Repurposing some federal land for affordable housing.

A ban on algorithm-driven price-setting tools for landlords to set rents.

Removing tax benefits for investors who buy large numbers of single-family rental homes

Only two are demand-centric (2 and 3), one responds to constituents’ concerns (8), and the rest focuses on supply. I’ve written a lot about housing and have done a series of interviews on it, most recently with:

And with Wally Adeyemo, Deputy Secretary of the Treasury (twice actually).

Policymakers are pretty aware that this is a supply problem, but demand-side support has to be a part of the equation4 because of the pencil-out problem. Even if we build, there is no way we can build fast enough to meet the demands for housing.

So all we need is more housing supply… right?

We Get It, We Need More Homes

Housing is important, for many reasons. This is clearly outlined in the 2021 Works in Progress article Housing Theory of Everything. They write -

Try listing every problem the Western world has at the moment. Along with Covid, you might include slow growth, climate change, poor health, financial instability, economic inequality, and falling fertility. These longer-term trends contribute to a sense of malaise that many of us feel about our societies. They may seem loosely related, but there is one big thing that makes them all worse. That thing is a shortage of housing: too few homes being built where people want to live. And if we fix those shortages, we will help to solve many of the other, seemingly unrelated problems that we face as well.

Many of the problems we face as a society are exacerbated by the fact that we don’t have enough homes.

The loneliness crisis, the demographic crisis, the wealth inequality (and subsequent regional inequality), the health issues, productivity, innovation - all of our issues are rooted in housing (rental and owned) being just a bit too expensive.

Housing is complex. As Derek Thompson has written, it’s meant to be both a (1) speculative asset and (2) a place to live. A retirement fund and a place to raise the kids.

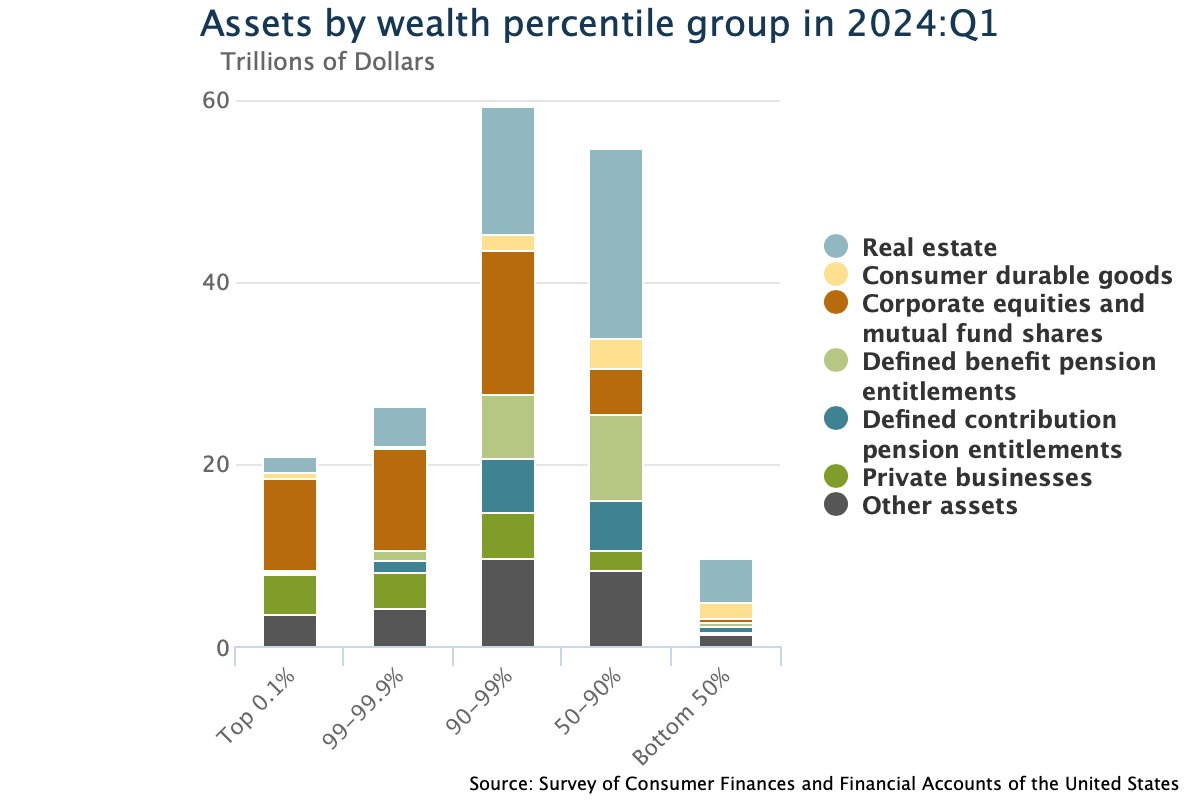

Those are impossible goals to reconcile. It’s exacerbated by the fact that the bottom 50% of Americans have all their wealth tied up in housing - versus the top 10% of Americans, who have their wealth in business ownership and equities.

One could argue that part of the reason we have had such negative consumer sentiment over the past few years is because of the structural affordability that prevents homeownership. Look at this chart. Look at the Millennials who have become Very Rich because they entered the housing market at the right time. Look at those who didn’t

We need 1.6 million homes to meet population growth, and we are nowhere near that.

But it’s tough to simply “build more” - like homebuilders need to build said homes, for example, and that’s not quite happening. There are severe supplyside constraints with sawmill capacity, as Joe Weisenthal of Bloomberg has written about.

You can liberalize zoning. You can cut red tape. And you can subsidize demand, and so forth. And some of that might help. But at least in the here and now, market conditions are serving to aggravate any future efforts to just expand supply.

Another reason it’s tough to “build more” is home insurance - which we need to consider in any conversation about building more housing.5

What is Home Insurance?

A few weeks ago, the market experienced a meltdown (I did a video on that here). It was a combination of yen carry trade, macro worries, geopolitical risk, etc. Mostly, it was being offsides in a high-risk environment, not expecting things to change, and then being in big trouble when they do change.

This same sort of mentality is happening in the home insurance market. Risk is materializing, but we just kind of... ignore it? Partly out of -

Necessity (how does one person fix the insurance market)

Overwhelm (what even is insurance)

And sheer exhaustion (another bad thing is happening, good, good, good).

Monday, August 5th, was a story of unexpected circumstances that were somewhat expected, and that’s what we are seeing in insurance markets.

An Insurance Market Overview

What is the insurance market? As Spencer Glendon and Barney Schauble wrote:

It’s important to understand that insurance isn’t - it is not protection against hazards like flooding, wind, fire, or hail. It’s a financial contract to reimburse property owners for the cost of repairing structures only after events that are predictably rare. If hazards stop being rare, stop being predictable, and/or produce damages that aren’t easily reparable (or suggest that a building should not be rebuilt in that location), the existing market structures for both property insurance and property more broadly won’t work.

It’s not protection. It’s a financial contract that relies on assumed stability. As the authors highlight -

Virtually all property insurance is annual. There is no term structure.

After a claim, the insured is expected to rebuild the same building in the same place.

Insurance is only available for damages to a structure, not to the value of the land.

Regulators often insist on using backward-looking data, prohibiting the use of climate models and climate-aware catastrophe models.

Regulators also regularly limit the amount by which insurance rates can rise year-to-year.

This gets into the underpricing of risk. A 30-year mortgage doesn't require a 30-year insurance policy; the insurance just renews every year (assumed stability). It also means the home, if something does happen, is expected to be rebuilt in the same place (assumed stability), and insurance (usually) doesn’t cover the value of the land. And most importantly, the data is backward-looking - and forecasting is an art, not a science.

Why Are Homes Uninsurable?

So what’s happening?

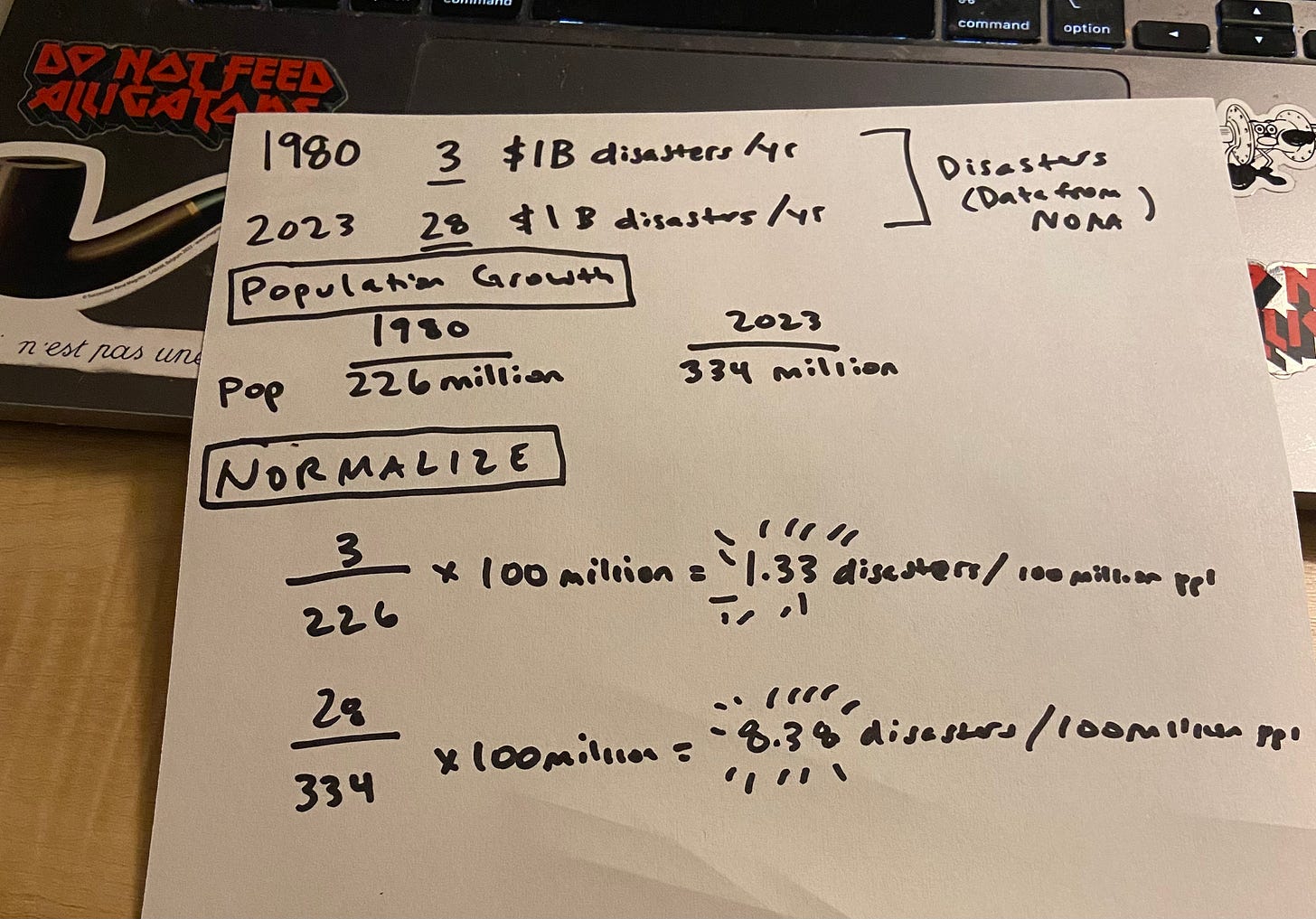

We had 28 disasters last year that caused more than $1b in damages6. In the 1980s, that number was 3 disasters. Over 2.5 million people were pushed out of their homes last year due to storms and fires.

Even if you normalize these numbers for population growth - the US population has grown by almost 100 million people since the 1980s (!) from ~226 million then to 334 million now. Doing the relevant math would result in 1.33 disasters per 100 million people in 1980 and 8.38 disasters per 100 million people in 2023.

The US government has rebuilt some structures 4 times (!!) over the past twenty years - at a huge cost. Fool me once, shame on me, fool me four times, time to move (if you can).

As the Washington Post reported

The 5 large U.S. property insurers — including Allstate, American Family, Nationwide, Erie Insurance Group and Berkshire Hathaway — have told regulators that extreme weather patterns caused by climate change have led them to stop writing coverages in some regions, exclude protections from various weather events and raise monthly premiums and deductibles.

Home insurers are telling regulators - “Hey, listen, the options are no insurance, underinsurance, and more expensive insurance. So buckle up.” The reason that home insurers are doing this is because they are losing a lot of money.

Home Insurers

US home insurers lost $15.2b last year, the most since 2000. Private insurance companies have to balance the risk of the policies they take on with plain vanilla investments and hedges. If the risk becomes too high, they stop writing policies!

Florida, California, and Louisiana all have had home insurers simply leave the market. But the problem is people like those states. California, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Texas, and Washington accounted for 53% of the country’s population growth between 2010 and 2020. Insurers don’t want to be there.

And you can’t live there if insurance isn’t there.

Homeowners

And of course, most homeowners didn’t know that their homes would be uninsurable. If you read interviews with those impacted , it’s devastating. These people who signed up for the American Dream are now facing the American Nightmare - and the startling reality that it’s not yours if it's not insured.

Insurance rates have increased by an average of 20% since the start of 2023. The average annual premium is $2,478, but it's over $5,000 in Oklahoma and Nebraska.

The rates are accelerating. Homeowners are paying 38% more for insurance than in 2019, with Arizona, Illinois, and Nebraska seeing over 55% hikes.

The reason that rates have skyrocketed for homeowners is because repair costs are surging due to inflation. Structural replacement costs have been 55% of the insurance increase between 2020 - 2022 - and that increase is due to the cost of construction materials.

There are also issues with insurance fraud (Florida accounts for 9% of home insurance claims but 79% of lawsuits over filed claims)

This impacts the entire economy. You cannot get a mortgage if you do not have insurance (you can still own a home, which is why we might see an increase in cash purchases in disaster-prone areas).

In January 2024, 32% of home sales were made with all-cash - so they don’t necessarily require insurance. But the 68% of people that still need mortgages absolutely require insurance. The real estate market certainly needs mortgages in order to keep on surviving. As Bloomberg wrote

Banks won’t make mortgage loans for uninsurable properties; without those loans, the real estate market slows to a crawl, which in turn eats away household wealth and the tax revenue that state and local governments rely on.

This insurance problem is not just an insurance problem. This is an economic and financial crisis. There are so many dominoes in the insurance line - real estate, tax revenue, etc - the housing theory of everything applies here too.

What’s The Problem?

So why is this happening, beyond climate change?

Regulation: Part of the problem is that some state agencies regulate rate increases, meaning that many people pay much less than they should to insure their homes. According to an example from Bloomberg - a California home that had a premium of $2,000 in 2010 was paying $4,820 by 2022. That’s an increase of 7% a year or so because California heavily regulates insurance price increases. But this massively underprices the risk - it should be closer to $8,000 in premium. This leads to disastrous results.

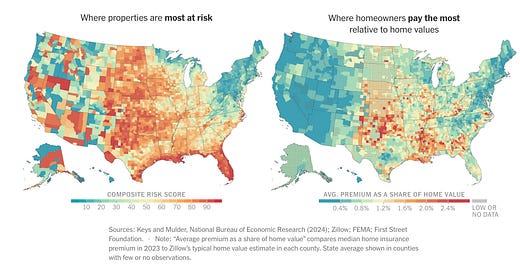

Two out of every three American homes are now underinsured. An estimate from First Street states that ‘39 million US homes are insured at artificially suppressed prices compared with the risk they actually face’.

And this also pushes the cost off to states that don’t regulate insurance as the New York Times reported. The article walks through the story of Enid, Oklahoma - the apparent riskiest place in the country to own a home (despite being far away from the ocean, having relatively low fire risk, and a very small population). In the U.S., homeowners pay an average of $500 in home insurance for every $100,000 in home value (in places like California, it’s more like $50), but in places like Enid, it’s more like $3,500 (!!) And when storms happen in tightly regulated states like California, insurers look around, shrug and raise rates in places that they can - like Enid, Oklahoma.

Reinsurance: Part of the problem is that reinsurers who insure insurance companies are raising their rates. Part of it is a land of higher interest rates, which means that all rates are more expensive. But the other part of it is the increased amount of small disasters. The reinsurers call them ‘secondary perils,’ so not big disasters, but things like wildfires and flooding, which are increasing. They raised prices on property insurers by 37% in 2023.

Building more: Part of the problem, somewhat ironically, is that we have built, Lance Lambert from ResiClub highlights7. Higher density in disaster-prone areas means more houses can be damaged, which means higher insurance. As Christopher Graham at AM Best said “Construction in catastrophe-prone areas adds to flood risk. It also increases the risk of wildfires in areas prone to them due to human activity, as well as utility companies.” More humans, more risk. It impacts all types of housing too. Los Angeles affordable housing providers have seen their premiums jump 400% to 600% in one year.

Pooling: The biggest part of the problem is that insurance is a shared pool a risk and there are a lot of spots in the country that can’t afford the risk anymore.

When insurers leave an industry, the industry can no longer function. That’s what happened to coal - 45 insurers left, and new coal-fired power declined by almost 90%, as Neha Mathew-Shah wrote. It can also keep industries alive - the insurance industry is propping up oil and gas (amongst other things), for example.

What is happening in insurance is not just because of climate change. It’s this mix of regulatory gaps (too much regulation in states like California and too little regulation in other states, like Enid) and a double layer cake of reinsurers and insurers, and a paradoxical twist - that if we build more homes, we need even more insurance than we thought.

What’s Next?

There is either a path of government or a path of cash buyers.

It will be the expansion of FAIR plans (Fair Access to Insurance Requirements) which are state-mandated property-insurance plans that cover people who can’t get covered by the market. Citizens Property Insurance in Florida is already the second-largest insurer in the state. Most of the state programs are not very comprehensive and are quite expensive, so we will need to see a reimagining of government backstops - but we will also have to think about what should be backstopped by the government.

If you buy a house with cash, you can skirt the insurance requirement. But, there are obvious consequences to that.

Some of it might be institutional buyers buying up properties and self-insuring, which has a melancholy ringing of 2008

How do we fix it?

Collaborative programs: make the FAIR plan more competitive or even partner with private insurance companies (or offer tax incentives) to offload some of the risk.

Microinsurance products: Offer small insurance alternative that are more flexible (and more expensive) but can patch coverage to homeowners who can’t find help

Legal reform: Reduce litigation costs and lawsuits. Make each party responsible for their own attorney fees so it doesn’t turn into endless legal battles. Streamline the approval process for rate increases.

Climate resilient homes: Build infrastructure for the future.

All of these things are expensive. But the cost of the risk is even higher. Once these places become uninsurable, no one can live there. You cannot take a mortgage out on a home that you can’t insure. We have to change our risk models.

Risk in General

So there was an entire mess with the BLS payroll revisions (revisions are normal) but this revision was massive. I’ve talked about the issues we have with economic data in a lot of the presentations I’ve given over the past few months8, and it’s becoming increasingly clear that the economic data we have isn’t telling the whole story.

It’s skewing our risk models. It’s a story for another article, but I think we are still using our pre-pandemic frameworks in a post-pandemic world. And that doesn’t work.

A slide from my recent talk at the OOO Conference last Saturday -

But if you zoom out beyond markets, it seems like the American dream relies on an outdated risk model. The American dream is based on home ownership, and home ownership is becoming extraordinarily risky.

Just like insurers have to update, so do we. We have assumed stability with the housing market and jobs and retirement plans, and that just isn’t a reality right now.

This model update will require us to reevaluate risk, across many sectors of the economy.

So many things are out of sorts. The data is a tapestry, but no one is responding to surveys. The birth-death model needs to be updated. We have a large segment wealthiest people hyperfocused on tax reduction versus building libraries because they feel like their money gets lost in bureaucratic red tape. What does this mean for our future?

I really liked this paragraph from Sami Sage

The focus on building generational wealth isn't just about the economy or people's finances, but a collective sense of mutual investment in American prosperity that we should all have a realistic and slightly more fair chance to share in. It's a return to the idea that if you work hard and play by the rules, you can build a stable future for your and your family. That question is kind of a lottery for people under 40, and people wonder why Gen Z is so nihilistic. “Nobody wants to work anymore” That’s because they no longer see the potential that working hard will appreciably increase their chances of achieving a financially stable future. I believe lots of people wouldn’t mind working harder if they did.

Another person pointed out that the defining trait of Gen Z (of which I am a member) is fear. We just have a different world than we used to, and risk in places it never has been before. The younger (and older!) generations are terrified of themselves and the world they live in because the path forward is so murky.

This leads to financial nihilism because trust is expensive, and that’s why we see a world divided, because the risk models are all wrong.

There are ways to fix it (like recognizing that things are changing, which is very hard). There are solutions, specifically for home insurance, but also the coasts are eroding into the ocean. There has to be an acceptance of the fact that the problems we face are big, and the solutions need to be even bigger.

Risk is manageable with the right hedges. We just need to update our models.

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice or recommendation for any investment. The Content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.

Most economists did not like her proposal to stop ‘price gouging’ at grocery stores and immediately jumped to a world with price controls on groceries. This topic is quite interesting because there’s a push and pull. Grocery stores have razor thin margins. But grocery stores did take advantage of supply chain disruptions according to the FTC. Kroger says they can do $1b in price cuts if they are allowed to merge with Albertsons, which implies some room to prices. Dr. Isabella Weber’s sellers inflation is probably the best story we have on how corporations respond in inflationary environments (by opportunistically raising prices, as any good corp would do)

For example, a recent news hit stated that Harris supports Biden’s tax plan at the DNC - potentially including an installment of an unrealized capital gains tax (which, to be clear, I think is a very bad idea). Those taxes will be impossible to push through, and with a repeal of the SALT cap on the table, we probably won’t get fiscal austerity anytime soon - from either side. A lot of policy announcements during campaigning are to get votes.

People really hate this. But the median home is like $400k right now - you need at least 20% down or so, about $80k. So $25k (if you qualify) would get you like 30% of the way there? And even if you get the $25k down, it doesn’t mean the bank has to approve you. Many people say this is a ‘handout’ that subsidizes demand but 78% of Gen Z homeowners and 54% of millennials had help on their down payment.

Noahpinion has a great piece on managing those two competing forces (with lessons from Singapore)

I struggled with publishing this because there is value in celebrating the good that is being done with housing. I feel like the guy emerging from a shadowy corner, tipping a fedora, and saying, “Isn’t there something you forgot?”

Part of this is the cost of solar panels which are damaged by hail / severe storms

This was my “oh no” moment

Here are the first 7 slides of that presentation

The solution is to let insurers price to risk everywhere. It doesn’t matter what your rate was last year. Regulators need to get out of the way.

If that means less beachfront property, so be it.

Very informative read - would love to know what you think is going to happen with insurance companies pulling out of FL, CA, and LA. What are the chances the government might do something similar to what they did with ACA and say, "You can't deny home insurance" the same way they say you can't deny health insurance coverage to people based on preexisting conditions?