How Monster Beverage is Fueling a Renaissance

one of the best performing stocks of the past 30 years

I am one of the cohosts of the Wealthsimple TLDR podcast, which you can listen to once a week!). I am sharing some of my recent stories. Also, if you would like to buy In This Economy? it’s available in print, e-book, and audiobook (narrated by me).

Unleash the Beast

Monster Beverage and Red Bull are funding a large part of the culture that would go entirely unnoticed—extreme sports, music, art, etc. They are the modern-day philanthropists, which is extraordinarily important in a world where those who would be funding culture—billionaires—are tremendously boring and distracted.1

Call it the Red Bull Renaissance or the Monster Medici’s, but these energy drink companies (for however you feel about the product) are doing work that no one else is really… doing.

What is Monster Beverage?

Monster Beverage is one of the best performing stocks over the past 30 years, returning over 22,000% with an annualized return of 31.1%. $10,000 invested in Monster Stock at the August 1990 IPO would now be over $22 million dollars. Not bad for an energy drink!

Monster technically began post-Great Depression as Hansen Natural Corporation, started by Hubert Hansen and his sons to sell natural juice. The company did fine, but got too ambitious in the late 1980s, with a plant expansion amid increasing competition in the natural sparkling soda market. The plant left them penniless, and they filed for bankruptcy in 1988.

South African investors Rodney Sacks and Hilton Scholsberg had raised $5 million from friends and family to buy a publicly traded shell company. They got a tip that Hansen Natural Corporation was floundering and decided to buy it for $14.5 million.

They originally wanted to get into packaging - but juice comes in a package, right? Good enough. The company was generating $17 million a year in sales (with $12m in debt) on five flavors of natural soda and apple juice when they purchased it (which hit $6.3 billion in sales in 2022 with 29 different products and over 17,000 patents).

At first, the guys didn’t know what to do with the company. Snapple was cool? So maybe iced tea? But this was also around the time of the rise of Red Bull in Europe. The energy drink market was hot - the AI of its time, perhaps - so, they decided to make an energy drink.

Red Bull seemed to have it all figured out. The drink that Red Bull is based on, Krating Daeng (red gaur), was first created in 1975 in Thailand. Former toothpaste marketer Dietrich Mateschitz was visiting Thailand from Austria in 1982, and upon drinking Krating Daeng and presumably experiencing a rush like no other, realized that energy drinks really did work. He partnered with Chaelo Yoovidhya to bring the drink worldwide.

So Red Bull came to life in 1987, a premium drink, first sold in Austrian ski resorts.

Monster followed suit and launched their first energy drink, Hansen’s Energy in 1997 (the same year that Red Bull entered the U.S.) to little fanfare. It was the wrong product to the wrong customers. The Hansen name had to go. So Monster switched paths and became Monster, launching the namesake product in 2002 in a can that was 2x the size of Red Bull for the same price.

And it worked.

Monster has never been focused on juicing shareholder returns, they just focused on running a good business. Rodney Sacks said once - "The stockholders are not our target [...] I'm not trying to persuade a 60-year-old fund manager [to buy shares]."2

And that rocks. That is so cool. It’s frustrating when companies optimize themselves into obscurity through feeble attempts to please the never-pleaseable shareholders. It’s great when companies focus on the product - which Monster has! They sell craft beers and seltzers and sparkling waters and alcohol and tea and coffee and of course, a variety of energy drinks.

The other impressive thing about Monster is that no one expected them to do what they have done. From a return perspective, it puts the various VC funds shouting into the void on Twitter to shame - just to reiterate - $10k invested in the early 1990s IPO would now be worth over $22 million dollars.

So what makes Monster such a good company? I think it’s partnerships, distribution, bullying, and financial management.

Presence

They are everywhere a party is. The festival, the track, the tailgate, the e-sports event. They are expanding into Asia with a more affordable line of energy drinks called Predator. They run an incredible social media presence - 45 million followers across platforms and 4.5 billion paid impressions. Online and offline, you can’t escape them.

Distribution

Monster figured out distribution almost immediately. They had a partnership with Anheuser Busch early on, a sign that they realized that they needed to quickly get these products to people. In 2014, Coca-Cola agreed to buy a 17% stake in Monster and swap some brands - Monster got Coke’s NOS, Full Throttle, Burn, Mother, and Play, and Coke got Hansen’s natural sodas, Peace tea, and Hubert’s lemonade.

And this is perfect, because no one knows the plumbing of how to get things to various places like Coke does. Coke is the Michael Jordan of distribution. Now, Monster can get into gas stations and at bars and at stadiums because they are working with the absolute king of logistics.

One might ask “well, why isn’t Coke a better stock than Monster?” and that goes back to the confusing nature of the stock market. And it’s a good question - the answer boils down to investor behavior and markets. Like GameStop is a terrible company but a very good stock (at least for a second there). Monster is a good company, but they are a great stock. They’ve specialized, refined their marketing, are constantly innovating on what consumers want, they move fast, and they have brand loyalty.

Bullying

Monster is also known as a ‘trademark bully’. Monster is incredibly protective over their intellectual property. They sued a company called Monsta Pizza of Wendover in Buckinghamshire, UK, because they claimed that people could get confused and think that it was Monster. They sue everyone. They actually lose a lot of their cases, but just sue, just so people know not to mess with them. This creates power behind their very distinctive brand. The bullying is expensive, but the knowledge of brand recognition and brand protection is accretive to their stock price.

Financial Management

The company is also just very well run. They’ve had 31 years of a trend of upward sales, and did $6.3 billion in net sales in 2022, which was almost a $1b increase from 2021. The stock has a relatively high PE ratio at 35, but the company has strong liquidity metrics and zero long term debt in its capital structure. They have high return on equity and return on assets measurements, showing they are efficient using the money they have to generate returns.

Partnerships

Finally, both of them have stellar partnerships. Red Bull does this thing called ‘brand myth’ where they don’t do much, if any, traditional marketing. Both companies sponsor extreme sports (like mountain biking, BMX, kayaking, NASCAR, parkour, etc), sponsor sports teams, and fund music festivals. Red Bull is extraordinarily impressive here - they have an art fellowship program, used to have a music academy that, according to the New Yorker

[...] helped nurture a cosmopolitan ethos within dance music. In Red Bull’s wake, other Web radio and live-broadcast efforts emerged, such as NTS Radio and Boiler Room, which reshaped how musicians and fans around the world saw and heard one another.

Red Bull unfortunately shut down the Music Academy that was focused on fostering creativity and getting people together who normally would not be together and “applying that degree of thoughtfulness to music that otherwise would not have broken through to wider audiences, or artists from marginalized communities worldwide” as Pitchfork wrote in 2019.

But still, they care about the communities that they are creating. 3

Billionaires and Culture

The thing is, we don’t have anyone doing this on such a large scale. We do have a lot of it in small pockets, and honestly, that might be all that matters. But on the mega scope, we don’t really have someone saying “hey yes the point of being alive is to make life easier for others.”

The public funding process is fine but wrought with review, paperwork, and lost time. Lots of corporations donate money to various causes, which is great, but it’s the ESGification of charity—fabricated metrics meant to tell a story rather than accomplish a goal. And of course, the billionaires are so lost in themselves that they are trying to catapult one another to a different planet.4

So somehow, we’ve ended up in a world where Monster Beverage and Red Bull are funding culture.

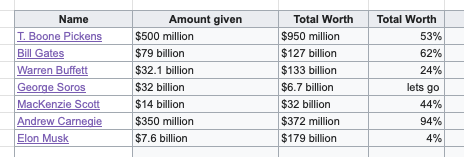

Back in March 2023, David Roth wrote ‘The Limits of the Billionaire Imagination Are Everyone’s Problem,’ a piece that dove deep into how uninteresting billionaires are. And with everything, there are exceptions—who am I to even begin to paint a broad brush stroke over humanity - but this is a table from Wikipedia showing the greatest philanthropists by USD.

I made an additional column to show how much their donations are as a percentage of their net worth (liquidity, assets, the immovable force of time, etc), which isn’t a perfect calculation, but it reveals enough, I think.

I do think that people like Bill Gates and Elon Musk have massively contributed to humanity - there is absolutely no question about that. Musk has paved forward the path in multiple industries, like electric vehicles and space travel, and Starlink is a modern marvel. Many people have made massive contributions. It’s all extraordinarily difficult. Liquidity, the noisiness of building, etc.

It’s easy to type these words into my five-year-old Macbook that hisses when I open Google Chrome and Mail at the same time, sitting cross-legged in the kitchen of my rented apartment and proclaim, ‘well if I was a billionaire, I’d do things so differently!’ Perhaps, I wouldn’t. I don’t know. But we have examples of how different things could be.

For example, Andrew Carnegie was at the forefront of the steel industry in the U.S. and gave away more than 90% of his fortune in the early 1900s. He had a three-part dictum that he followed -

To spend the first third of one's life getting all the education one can.

To spend the next third making all the money one can.

To spend the last third giving it all away for worthwhile causes.

He donated to colleges, built church organs, and funded over 3,000 libraries. He was a backer of the National Conservatory of Music. He founded the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, now known as Carnegie Mellon University. He created the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. He founded the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He built Carnegie Hall. He was a large benefactor of the Tuskegee Institute. The list goes on and on.

And, of course, Carnegie, like most billionaires, ruthlessly pursued money. Joseph Wall said - "Maybe with the giving away of his money, he would justify what he had done to get that money." In 1889, Carnegie published The Gospel of Wealth, outlining the purpose he thought money should serve. It wasn’t something to be accumulated. It wasn’t meant to get stuck in vortexes, shuffling from one index fund to another. He writes

Individualism will continue, but the millionaire will be but a trustee for the poor; intrusted for a season with a great part of the increased wealth of the community, but administering it for the community far better than it could or would have done for itself.

That’s probably the way to think about all this, right? Part of the problem that we have right now is wealth hoarding, assets trapped in expensive houses and illiquid markets. Richard Florida of Bloomberg’s CityLab wrote a haunting paragraph on wealth in America

Instead of driving more innovation and growth, the bounty from today’s knowledge economy is instead diverted into rising land costs, real estate prices and housing values. The result is that working- and middle-class Americans are forced to devote ever-larger shares of their hard-earned money for shelter. The central contradiction of capitalism today is that a huge share of its productive surplus ends up being plowed back into dirt.

A doom loop of sorts.

What are books, really?

One of Carnegie's libraries was turned into an Apple Store.

The Carnegie Library had been underutilized for decades. Due to overcrowding, it stopped being a library in 1970 and turned into the City Museum of Washington D.C. in 2003. That ended in 2004. So, nothing really worked for the Carnegie building.

And Apple did renovate the building and offer classes on photography, filmmaking, music, and coding, which is wonderful.

We talk of the loneliness crisis, of not having third places, of being so separated from one another and connected to technology, and libraries are a place to placate that. But we also have a cultural crisis of sorts, where the money is going to all the wrong places and we are losing so much with the displacement of cultural producers and cultural spaces (something Tanvi Misra captures well in this article). As Kurt Vonnegut wrote in Palm Spaces -

What should young people do with their lives today? Many things, obviously. But the most daring thing is to create stable communities in which the terrible disease of loneliness can be cured.

When I was growing up in Kentucky, I’d go to the library once (sometimes twice!) a week with my mom. I would get about ten books. I would read voraciously, as a lot of little kids do, recognizing myself in characters and stories and then being exposed to character and stories far beyond myself. But I never would have read as much as I did, nor have had a place to get math tutoring in 3rd grade, when I moved classes in the middle of the year and feel behind, nor have had a place to sit before school started when the bus dropped me off if it hadn’t been for libraries.

The NYC libraries have experienced mass budget cuts - about $58 million in total. Apple makes $157 million a day, according to Tipalti. And I am not being fair in that comparison at all - it’s apples and oranges, but both are fruit, I suppose.

And perhaps, it is enough that the library is now an Apple Store, because surely, the amount of information we get from the phones and the computers is equivalent to that of the books, right?

But perhaps, it is not enough. Perhaps, the library becoming an Apple Store is emblematic of how we think of culture in general - a replaceable commodity, an interchangeable unit, simply 0s and 1s of input into our brain rather than a holistic experience that supersedes learning for optimization.

There was a piece from New Scientist around chatbots as emotional support tools, and how they can’t technically be empathetic. Sherry Turkle writes “It’s a sad moment when we think that being lonely can be fixed by an interaction with something that has no idea about what it is to be born, about what it is to die.”

I think about that, in context to the books. One of my favorite quotes by James Baldwin is regarding the shared stories that novels allow -

“You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

There is also a beautiful line from an Ethan Hawke interview -

Most people don’t spend a lot of time thinking about poetry, right? They have a life to live and they’re not concerned with Allen Ginsberg’s poems or anybody’s poems! Until their father dies, they go to a funeral, you lose a child, somebody breaks your heart, they don’t love you anymore. And all of a sudden, you’re desperate for making sense out of this life… or the inverse - something great. You love them so much you can’t even see straight! You know, you’re dizzy! And that’s when art’s not a luxury, it’s a sustenance. You need it.

And we do need it. I love progress and technology and growth and think it’s all important, and think that all of them can be art forms and contain bits and pieces of beauty. But I think how progress and technology and growth comes to us is overwhelming. This is a long way to say fund the libraries and art centers etc. Apple has done a tremendous job at maintaining the building, but there is something deeper to examine there.

Back to Monster

I went to the Sphere this past weekend. The Sphere was funded by Cablevision king James Dolan and his company, Madison Square Garden Entertainment, so perhaps I should put away my keyboard. The Sphere is one of the most impressive pieces of industrial mechanics I have ever seen (and they used the world’s fourth largest crane to build it, which required another crane to assemble it). The billionaires do build.

But also, we can’t blame this on billionaires. It’s incentives. You used to be able to circumnavigate tax law (ahem, evade) by investing in culture. James Cameron got his start in movies because a bunch of dentists were like “hey man, the tax guy is coming… make that weird short film, you 24-year-old'“. The projects would lose money, make money, whatever - but they funded an entire generation of entertainment upstarts.5

I am also being too critical of the power that they have. They are people, too. One of my big takeaways from seeing the Grateful Dead at the Sphere was the power of affordable housing. Like imagine that you’re a bunch of dudes, in San Francisco, times are tense but is rent is cheap - so you make music. And you play in venues. Because you can afford the risk.

Alex Yablon wrote the great piece Negative Yield New York, which I’ve talked about before, about how powerful it would be to have manageable rent in cities

But once the city gets access to extremely low-interest credit, it could also invest in massive amounts of new housing to drive down the cost of living as well as cultural infrastructure: the city could create new studios, rehearsal spaces, galleries, and performance venues to ensure that its vital artistic economy can thrive alongside other sectors that have increasingly crowded out the underground.

So, could the billionaires do more? Of course, naturally. But there are acute issues that supersede what they can achieve —and in accordance with the ironclad law of The Housing Theory of Everything, some of it can be addressed by addressing housing.

A Quick Aside on Housing

I interviewed the Deputy Secretary of the Treasury, Wally Adeyemo, about the U.S. Treasury’s new housing initiatives - here is a snippet. You can listen to the whole thing wherever you listen to podcasts, or see me wave my hands around in a garage on YouTube.

Kyla: Recently, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen gave a speech in Minneapolis, celebrating the city's progress and announcing new federal initiatives to support affordable housing nationwide. But Minneapolis isn't alone in this endeavor. Cities like Austin, Texas, and Burlington, Vermont are following suit with their own zoning reforms. It's part of a growing recognition that the path to more affordable housing often begins with changing the rules that govern what can be built where. Of course, zoning reform is just one piece of the puzzle. The Treasury Department is rolling out a series of new programs to make housing more accessible and affordable. Let's break them down:

First, there's a new program that will provide $100 million over the next three years to support affordable housing financing. This money will go through the Community Development Financial Institutions Fund, or CDFI Fund.

Deputy Secretary: What these institutions do is they are located in communities, especially communities that don't have access to big banks. Even in rural states like Idaho, you have a housing shortage. And what the CDFIs are doing is they're giving this money to local developers who are building affordable housing on a regular basis there. And this 100 million is money that is coming into the CDFI program that they're going to recycle back into these CDFIs to help build additional affordable housing, especially in communities that are in rural areas or in urban areas that lack traditional banking access.

Kyla: Then there's a program aimed at providing interest rate predictability. This might sound dry, but it's actually crucial for developers. The Federal Reserve has been raising rates in order to battle inflation, but that’s actually made the housing problem much harder to manage. New home construction is at its weakest level in 4 years. It varies across the country too - as Conor Sen of Bloomberg Opinion highlights, single family inventory levels in many parts of the Northeast are 70% or more below pre-Covid levels.

Deputy Secretary: Let's say it takes you a year to finish building the house, and then you go out and get a new loan, and the interest rate has moved so much that it's unaffordable for you to continue to get that new loan, to continue to carry the home. What this program does is it helps the builders lock in the interest rates that they're going to get for both of those loans.

Kyla: The Treasury is also updating the Capital Magnet Fund to reduce administrative burdens. It's all about cutting red tape.

Deputy Secretary: A big piece of what we've done is reduce the paperwork burden in order to make it so much easier for someone who's trying to build affordable housing to be able to claim it.

Kyla: They're even creating a how-to guide to help developers navigate the complex world of housing finance. It's like an IKEA manual, but for building affordable housing. But perhaps most importantly, the Treasury Department is pushing for better integration between housing and public transit.

Deputy Secretary: We passed a historic infrastructure bill in the federal government, which is going to lead to better mass transit in many cities throughout the country. Now the key has got to be that cities make it easier for people to build housing around that mass transit.

Kyla: The road to solving America's housing crisis is long and complex. It will require patience, creativity, and collaboration at all levels of government. But cities like Minneapolis are showing us that change is possible. They're proving that with the right policies and a little imagination, we can build cities that work better for everyone. As the Deputy Secretary put it:

Deputy Secretary: Housing matters so much because it's more than just four walls. It's the key to where you have your family. It's where you have your meals. It's close to where you work. We want to make sure that people have housing that's located near opportunity.

Opportunity. That’s what Monster Beverage provides. That’s what it’s all about. And that’s why Monster Beverage is so important. This is the power of unexpected sources of cultural support. When we think of the traditional pillars of culture, large parts of it were funded by billionaires or made smoother by more affordable housing. Compound those lack of those two variables and you get where we are now - frustration, distrust, all of it.

Monster Beverage is a tremendous company because they have funded these weird parts of culture that would have normally been funded by billionaires. That’s not why their stock is moving the way it does, but it probably doesn’t hurt. Going back to Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth -

Individualism will continue, but the millionaire will be but a trustee for the poor; intrusted for a season with a great part of the increased wealth of the community, but administering it for the community far better than it could or would have done for itself.

I think things are just sort of stuck. The reason Monster Beverage is exciting is because they have unstuck many things and they see things as community-oriented. We need more of that. We need more Monster-type energy.

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice or recommendation for any investment. The Content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.

Thrive Capital just invested in A24, so please, nuance etc

So many lessons in that sentence

Monster has health risks as all energy drinks do

This is an incredibly reductive paragraph and forgive me for generalizing so heavily.

This changed in 1986 when the tax law changed. Incentives!

Thanks for this Kyla. Definitely piqued my interest and was curious to learn more. While you bring up some interesting points about the value of Monster in funding arts and culture, I think this is missing more content on two important details:

- The types of arts and culture they are funding

- Like Carnegie, what they are doing to acquire the funds to distribute elsewhere. Important to note the negative health impacts linked to consuming energy beverages - which this digest is lacking.

This was a wonderful, remarkably rich and thoughtful post.