The 'Biggest Man-Made Disaster' Ever?

the longshoremen strike and the democracy of automation

For the first time since 1977, the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) went on strike. ~45,000 dockworkers have started picketing at 36 US East and Gulf ports - from Houston to Miami to New Jersey. This comes at a very intense time with escalating geopolitical tensions, a presidential election in about a month, and a hurricane that devastated the lives of millions of people.

This strike represents about half of all US trade volumes. It puts $2 billion at risk per day in trade, and the economic loss could be as high as $5 billion a day. A strike that lasts only a week could take a month to clear. Some might say that’s mere pennies compared to the size of the US economy ($29T), but this is about more than just dollar signs.1

Because strike is about more than just money- it’s about the democracy of automation.2

The Longshoremen Strikes

Many people are dismissive (“pay them off,” etc.), but Harold Daggett, the president of the ILA (more on him later), says he will go anywhere there is a threat of automation and help those workers go on strike. This will not go away unless automation goes away, which is not what we want to happen.

This has happened in other industries, too—the auto industry and the UAW, Hollywood and the writers—and these rolling strikes will continue to occur unless we talk about the role of corporations in automation and the workers that it impacts.

The Players

There are two main players here - the longshoremen and the USMX.3

Longshoremen, at the most basic level, use various machinery to load and unload containers at the ports. It’s a job you can be grandfathered into and pays quite well (although, as David Dayen points out, their wages have dropped). Their jobs are very important because the US imports a lot of things. Walmart, for example, is one of the companies most impacted by the strike.

The longshoremen's contracts with the ports are negotiated every six years. Since 1977, things have been smooth sailing, but this time, they want:

77% wage increase over the next six years (much higher than the 32% raise secured that West Coast dockworkers got)

A ban on the automation of cranes, gates, and container-moving trucks

Better job security, touch fees, which are payments made to longshoremen for each container they handle (interesting thread on that here), etc

But basically, they are like, “Hey, pay us more and also do not automate away our job. Thanks.”

They are negotiating with USMX. These terminal operators and ocean carriers run the ports that the longshoremen work at.

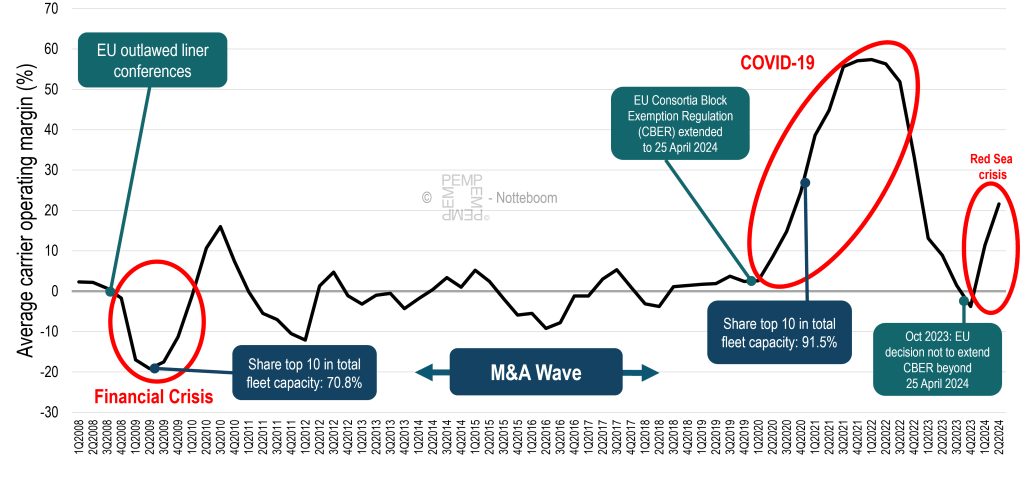

They are also an interesting natural economic experiment - the top 10 container lines have 90% market share4 and they actually benefit from a strike (misaligned incentives, my old friend, it’s been too long). They make more money when capacity is tighter and as Bloomberg Intelligence reported - “the supply snarls make help the container industry’s earnings into the fourth quarter”

😐

Ocean carriers benefit from soaring freight rates. As CNBC wrote “UBS estimated that if freight rates increased 30% over two quarters, a revenue tail wind of more than $1 billion would be generated.” Rates have already gone up about 30% -

A 40-foot container costs about $4,000 to $5,000 to ship to the US from Europe, but now there are peak-season and strike-related surcharges adding another $1,500 to $2,000. In just a few weeks, the rate has gone up 30% to 40%.

The problem here is EVERYONE profits from a little bit of inefficiency. The friction is in all the wrong places. But both sides are willing to talk - so let’s get into the demands.

The Demands of the Longshoremen

Higher Wages

The first part, higher wages, makes sense. People should be paid more. The members of USMX have made a lot of money over the past few years with the pressure of COVID and other supply chain snarls, so of course, other supply chain components will want a piece of the pie.

Automation

The second part, a ban on automation, makes less sense. USMX came to the same conclusion. The USMX has counteroffered to the longshoremen's demand with an offer “to increase wages by nearly 50% over six years, triple employer contributions to employee retirement plans, strengthen health care options, and retain the current contract language around automation and semi-automation.”

The ILA rejected that offer. Why? The automation language.

This is not the first time that the ILA has opposed automation. The ILA opposed containerization - an innovation of the 1950s. But just like anything, the technology happened anyway. Containers reduced per-ton loading costs from $6 to $0.16, and saved countless longshoremen from being crushed by loose cargo. As the Financial Times wrote -

Ultimately, the unions could not prevent containerisation, but they sought to slow the pace and extract economic rent for themselves along the way, which is also what’s happening now.

The 1977 work stoppage lasted 45 days. Trade was 16% of the economy then (it’s 27% today) and $4 billion of cargo piled up, Puerto Rico had to fly in groceries, and the ILA ended up winning. For context, $14 billion in trade came in the week before the 2024 strike.

USMX wants automation because it ultimately wants to make more money. The ILA does not want automation because it wants to protect its jobs.

The Push and Pull of Efficiency

The ILA president is a man named Harold Daggett, a third-generation ILA member clearing over $700k a year. He owns a yacht and a Bentley. He said in a recent interview -

I'll cripple you. I will cripple you, and you have no idea what that means. Nobody does.

Harold Daggett does not want automation. Biden seems to be like “Let loose, Harold” and doesn’t seem to have a plan to invoke Taft-Hartley, a 1947 U.S. federal law restricting the activities and power of labor unions that allows the President to intervene in strikes that could create a national emergency, to break up the strike. Even if Biden did invoke Taft-Hartley, Daggett is like “We will work really slow 🙂 you cannot escape this.”

But this is where the conversation is tough.

This strike is putting 48% of active pharmaceutical ingredients at risk. It’s happening as North Carolina and other states impacted by Hurricane Helene try to rebuild themselves. It’s happening as the Red Sea remains closed due to global tensions. It’s happening without any backup plans because the US Coast Guard is underfunded and the Merchant Marine committee was shut down.

Not only is this reducing GDP by an estimated $5 billion a day, but these 45,000 people are also impacting 600,000+ other jobs and are impacting $240 billion in goods. It's impacting billions and billions of dollars and could create massive inflationary pressure.

Economic and Societal Impacts

Economic

There’s an economic impact to this, clearly. It’s happening as we just managed to get inflation under control. The Cleveland Fed inflation nowcast had inflation 2.00%. The Fed has started cutting rates and seems to want to continue to do so. But this supply chain crisis could be massively inflationary - and it comes on the back of a weakening jobs market. It’s really hard to get a job right now - the hiring rate is at 3.3%, the lowest since 2013. We do not want supply chain inflation. If this strike isn’t sorted, we will have supply chain driven inflation.

Societal

But there’s also the societal impact. This is not the first time there have been strikes against automation, and it won’t be the last. Bloomberg had some very thoughtful paragraphs on automation and the push and pull -

Similar to the US auto workers who went on strike last year, and to the Hollywood actors and writers who picketed before that, the nation’s longshoremen are keen not only to improve their wages but to protect their jobs from machines that can perform a growing number of tasks without human intervention. Meanwhile, employers at the ports view increased automation as necessary to their competitiveness and ultimate survival.

The push-pull of technology raises deep questions about the time frames each side is operating on. Workers concerned about job security will need to balance the near-term threats with the longer-term risks. And employers that claim they want to invest in automation for the sake of being competitive in the long run will need to decide how long they’re willing to stay shut down because of it.

So which is the bigger threat in the end for port workers — robots that can scan trucks, stack containers, and transport goods, or a reflexive resistance to using them? We’re seeing the answer play out now in a strike that could reduce GDP by an estimated $5 billion a day.

People want safety.

My boyfriend doesn’t use much technology at all—he doesn’t have social media and barely uses his phone—and it’s because he doesn’t like what all the tech does to us. He invests in vinyl and steel bikes because that technology still works - and efficient technology doesn’t mean it will last long.

He isn’t alone in thinking this. Blood in the Machine talks about what happened 200 years ago when the Luddites rose up against automated machines. They wanted (existing) protections to be enforced and respect for the worker. Brian Merchant, the author, writes

The biggest reason that the last two hundred years have seen a series of conflicts between the employers who deploy technology and workers forced to navigate that technology is that we are still subject to what is, ultimately, a profoundly undemocratic means of developing, introducing, and integrating technology into society.

And this is where the meat of this conversation is at for this piece. How do we talk about automating society? It’s all fine and grand and good for the tech people to talk to other people on tech podcasts to tech listeners, but we need a PLAN for what automation will do and how we will care for the workers impacted.

Public Perspectives

I published a YouTube (and podcast and short form videos… you know the drill) on this topic, and the top comments were (my own notes are out to the side) -

Why do economists always talk about rational self interest as a good thing when it comes to management but they say that the worker should always act for the "net good" of society ??? (hypocrisy)

I think it's disingenuous to frame this as "the economic impact is because of the longshoremen". As always, it is corporate greed that is at the center of the need for the longshoremen to strike in the first place. The blame lies firmly at the feet of the corporations who want to squeeze every last penny out of every single job to the detriment of everyone else. (accountability)

I'm an engineer and part of a trade union. I agree that they should strike for higher wages given the profit growth of the companies however the automation argument is tricky. It sounds like they want to ensure job security and view a ban on automation as a garuntee on that however I wonder if a commitment to upskilling longshoreman to be able to operate the incoming equipment would be a suitable compromise ? (compromise)

Many upper middle class corporate jobs could have been automated 10-20 years ago but managers won’t because it’s not in their interest. These dock workers are fighting for their lives right now. Automation is inevitable but corporate America is deciding to start with the working class. I’d be angry too! (inequality)

When the owning class institutes automation it means layoffs. If the working class owned the ports automation would mean vacation days. (ownership)

The core themes of these comments are the hypocrisy of economics, corporations' lack of accountability, the compromise required to make this a long-lasting agreement, the inequality of automation, and what ownership means in an asset-based economy.

All of these comments are right, in a sense. The first comment is right that ‘maximizing shareholder value’ is framed as a positive thing but when workers say, “Hey, our jobs,” which is framed as greed. And societal net good is complicated. And there are several important points to make here -

Automation takes a lot of time and a lot of money. The longshoremen don’t want any of it, but even if the ports completely win, it would still take 4-8 years to automate fully and roughly $1 billion.

The US ports are VERY inefficient: Los Angeles and Long Beach are dead last out of all 370 ports in the world. New York and New Jersey are below 251. The ports are inefficient because we do not use automation. We are about half as efficient as other major countries, and part of that is because of the longshoremen. The cost of that inefficiency is then passed onto the consumer. It is also very embarrassing for the US, the world’s richest country, to be last at anything.

Automation has eliminated 5% of jobs so far: As More Perfect Union (inadvertently) tweeted, “One union-produced study found that robots eliminated 5% of port worker jobs on the West Coast,” which is about 2,250 jobs.

So we can automate a bit. And to be clear, we should.

But going back to the comments -

Open AI just raised the largest venture capital round ever because Sam Altman is a master fundraiser. People are very excited about what AI can offer but there is no sense of democracy in the implementation. They just do things, which is how it always is. They move fast and break things, and the things they break can be people’s lives. And that’s just the American way and it’s brought a lot of efficiency to society but it’s probably time for some plan to take care of workers.

We can automate. But workers should be a part of it. As many others have written about we should consider labor force retraining, transition assistance, skills diversification, union-management involved with automation decisions, sharing of productivity gains and broader profit sharing, running the ports as co-ops, and new job creation within automation—these are all things that really matter as we zoom ahead with technology. We can’t just pay these people off because it’s a problem much, much bigger than just money. It’s people’s lives.

The 2024 longshoremen strike represents more than just a labor dispute; it's a microcosm of the larger societal challenges we face as we navigate the future of work in an increasingly automated world. There is a growing tension between efficiency, job security, corporate interests, and worker rights.

The path forward is not clear, but what is clear is that we need a more democratic, inclusive approach to implementing new technologies. It’s all uncertain, creating ripples that can be harmful in the long run. Nothing can be smooth sailing, but the key is to support workers through changes, not just replace them with machines.

None of this is new. But some of the above ideas should probably be implemented so the entire global economy isn’t at risk at various frequency as we adapt to AI, machine learning, automation, etc over the next few years.

Economically, all of this is (hopefully) going to be a drop in the bucket - if the strike gets resolved within a week (~80% chance of happening, according to Flexport CEO), then economic activity will normalize.

I realize how idealistic this sounds and I promise I try to remain rooted to reality throughout the article

There are a lot of good people in the shipping industry talking about this and I am pulling heavily from their research - all sources are linked!

Monopolists are also very good at passing along costs. So the costs hits carriers, then merchants, and then you and I, the esteemed consumer

This all comes back to the fact efficiency has gone up 170% in the last 50 years but wages are stagnant. People have been led to believe it's government inefficiencies that are the cause but federal government spending as a percentage of GDP is the same at ~22% since 1970. What has changed is corporate tax code. As efficiency has been gained the corporate tax rate and top marginal tax rate has plummeted from an effective 50% rate in 1960 to 13.3% in 2020. If we want to make progress, and not turn every american worker into a card carrying Luddite, that mix has to change. The longshoremen should be asking for 50% profit sharing, not a wage increase, that way they are incentivized to be more efficient and are on board. As well as a generational trust fund for workers who are displaced due to efficiency. (Shh don't tell them this is called UBI).

It's a torturous balance. It's crazy not to use technology/automate to a degree for cost and efficiency, but not all technology is good (whether it's just badly designed, not always safe etc.). And disruption by automation is painful, as it means the displaced workers will ultimately need to retrain for new jobs since their old ones don't exist anymore. The real problem is that these are all extremely subjective issues in terms of how much corporations AND governments owe the disrupted workers in terms of helping them retrain etc. Each political party will be on the side they are always on. I certainly wouldn't want to have to ordain where that balance is.

I sympathise with your boyfriend, though I'm not anti-tech per se, I'm just anti a lot of it that doesn't work well/bad UI/UX & stuff that is rather dehumanising. I also hate how it is hard to get through the day if I forget/don't charge my phone. But stuff like Lime bikes in a big city with gridlocked public transport (& where you get fed up with owning a bike due to wheels being nicked all the time) are amazing. And I still find it amazing that I can talk into my phone & it will transcribe it all on the fly - I used to dream of that.