some thoughts about the structure of work

So there is this video floating around of a woman talking about her first job, and how hard it is to balance work and life. She can’t live in the city because she can’t afford to, so she has to do a lengthy commute into work. She can’t balance a social life because she is doing this lengthy commute into work. She’s fine with her job, but feels like she doesn’t have time for anything - a perfectly reasonable response to overwhelming stressors!

Of course, a lot of dumb accounts that don’t know how to read, are sharing the video and saying things like “this is what the real world is, little girl!!!” or “Gen Z girl finds out what a real job is like” which totally misses the point of her video. She said, verbatim, “this has nothing to do with my job” - she is talking about the structure of the 9-to-5. The balance of going into the office for the office job to do office work and how sometimes, it feels like there isn’t much outside the liminal spaces of the concrete walls.

And to be fair, the structure 9-to-5 is a relic of the industrial revolution.

The History of the 9-to-5

In agrarian societies, people often worked with the sun - waking when it rose and then sleeping when it set. But when everything became Big Machine in the 19th century, there was a need for standardization of work hours. So they were standardized, to the tune of 16-hour work days in factories, six days a week, children included, which of course, was not ideal.

Workers started fighting back, led by unions. Robert Owen (a fascinating man who tried to develop socialist utopias) coined the term “eight hours labor, eight hours recreation, eight hours rest” - but it was a battle to get there. Employers hated unions, and would fire union members, recruit strikebreakers, and hire people to break the knees of anyone that tried to change how things worked.

The 1886 Haymarket Affair is just one example out of many of how bloody things got. It began as a peaceful rally for an 8-hour workday, but someone threw a dynamite bomb at the police, killing and harming both civilians and police. This resulted in the conviction of 8 labor leaders. 4 of the leaders were executed.

That’s a simplistic and reductive summary1 of a time that was dynamic and changed the world, but things were incredibly tense between employees and employers. The way that communication happened between the two was strikes - employees withholding labor so employers could not generate capital. And so it continued. Any reduction in working hours was met with a subsequent reduction in wages.

Until 1914.

Ford Motor Company was one of the first corporations to adopt the 8-hour workday in 1914, doubling wages to $5 a day which led to their productivity skyrocketing and their profit margins doubling from $30 million in 1914 to $60 million by 1916. As Daniel Gross wrote in Greatest Business Stories of All Time:

On January 5, 1914, Henry Ford announced a new minimum wage of five dollars per eight-hour day, in addition to a profit-sharing plan. It was the talk of towns across the country; Ford was hailed as the friend of the worker, as an outright socialist, or as a madman bent on bankrupting his company. Many businessmen -- including most of the remaining stockholders in the Ford Motor Company -- regarded his solution as reckless. But he shrugged off all the criticism: "Well, you know when you pay men well you can talk to them," he said. Recognizing the human element in mass production, Ford knew that retaining more employees would lower costs, and that a happier work force would inevitably lead to greater productivity. The numbers bore him out. Between 1914 and 1916, the company's profits doubled from $30 million to $60 million. "The payment of five dollars a day for an eight-hour day was one of the finest cost-cutting moves we ever made," he later said.

Henry Ford did a few things - recognized that short-term cost cutting resulted in long-term issues, recognized his employees as people, and saw wealth as something to distribute, not just to hoard.

Of course, once one company does it (and it works) other companies have to do it too. It was a while until it was made law, but the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 set the maximum workweek to 40 hours a week, created time-and-a-half overtime pay, set the right to a minimum wage, and prohibited child labor.

So we’ve made a lot of progress since four-year olds were doing hard labor on an assembly line, but progress never really ends.

The 9-to-5 Now

So now, things are a bit different. Time to progress again.

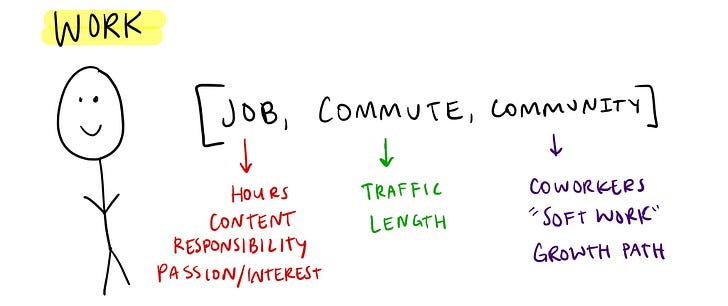

Work can be broken down into the job, the commute, and the community.

For the job itself, it’s a function of hours, content, responsibility, and passion.

The commute is a function of traffic and length.

Community at work is coworkers, the ‘soft work’ which is the conversations that take place in-between the ‘hard work’ as Derek Thompson calls it, as well as the growth path.

For many, the 9-to-5 is a job that sorta-maybe isn’t satisfying (and for many people, that’s fine, work can be profitable drudgery), a commute, and some sort of path forward with people around them. It can feel like a perpetual cycle of work and rest with little time for personal pursuits.

There is increasing friction with the structure of work.

And of course, the 8-hour work day was a celebration! It was incredible that we achieved that. But something that once a celebration of workers’ rights over a century ago is probably something that needs to be reexamined.

There is the bifurcation of everything, across many lines.

Laptop jobs versus in-person work.

Traditional industries versus B2B SaaS (and things like it)

There are a lot more types of jobs now because we have more things to do now (although most people still work jobs that existed 100 years ago) but still, this frame of 9-to-5 work remains the same.

Of course, it isn’t really a “9-to-5” but the artifact of a 20-30 minute commute, a full workday, and then a 20-30 minute commute home remains pretty standard for most office jobs.

I am familiar with this! When I worked in Los Angeles, I had a 15-minute scooter to the Westside office (or a 45 minute train ride to the downtown office) and I usually was in the office around 5am (West Coast companies working East Coast hours). I then would work until a time that maybe was less than ideal, and then would scooter or take the train home (or get a ride from a very generous friend). By then, it was dark. I was tired.

Of course, 6 months after I joined the workforce, a pandemic happened, so it was a different experience as most of my adult life (3.5 out of the 4 years) has been remote.

But when you first join the corporate life, especially right out of school, it’s incredibly jarring.

How Work Works

The younger generation, notably Gen Z, grapples with an evolving definition of work. Unlike previous generations, they face unprecedented challenges: climate change, an uncertain economy, ballooning student loans, and the struggles of identity and purpose in a digitized world.

I’ve written extensively on Gen Z’s relationship to work, one piece with Fast Company and then another exploring financial nihilism and then another about the meaning of work within the younger generation and how they relate to the world, work, others, and themselves -

This generation has to go about things differently. Gen Z seems to be searching for broader freedoms in a world dominated by corporations and advertisement and also if you have a feeling just medicate it and also student loans and also the housing crisis and also hyperindividualism and also the Earth is burning so there is nothing left to do but try and save it…

The younger generation has grown up in a time of economic turmoil, an unwritten redefinition of the standard of living, and interconnectedness that at times is painfully restrictive.

And

Work has evolved around unnecessary provisions - the age of surplus created the jobs of excess. The only way to stay ahead is to produce, produce, produce, but that’s been increasingly weird. When people sat back after the 2016 election and during the pandemic, too many truths began to break the pattern of the story we had told ourselves in this age of Industrial Maturity about the work we do… And in that process, many came to a weird realization (especially in rather work-focused USA) that their work might not be the key to self-actualization. And for some people it is - but for the vast majority of people, it might not be. And that’s where things get sort of weird - the pattern gets messed up in our work story. The work isn’t what we thought it would be.

Derek Thompson has published extensively on work, charting the rise of the managerial class against the decline of religion and the rise of workism -

Many people today ask their jobs to provide community, transcendence, meaning, self-actualization, existential therapy—all the things we have historically sought from organized religion. These workers—particularly, highly educated workers in the white-collar economy—feel that their jobs cannot be “just jobs” and that their careers can not be “just careers.” Their jobs must be callings.

And if you feel like your job isn’t a calling that feels bad. But in this video, the woman isn’t even talking about the work itself, she’s talking about the structure of work.

But what is hard work?

Steve Schwarzman, the CEO of Blackstone, said that remote workers ‘don’t work as hard’. And it’s sort of like well what is ‘hard work’?

Is that something that is measured by productivity or worker happiness?

Maybe hard work isn’t smart work - I know a lot of investment bankers who work hard, but also spend a lot of time waiting - it’s work sure, but is it smart?

Maybe things don’t have to be how they always were.

And the concept of ‘hard work’ is a religion. We bow to the altar of profits or whatever, and that shapes how we work - but maybe we can work smarter? We must ask if our current work models are smart and sustainable, especially given our technological capabilities.

Also, work doesn’t promise what it did. Maybe it’s easier to swallow the commute when home prices are in reach and things feel more tangible. It’s increasingly more difficult to finance life on a 9-to-5 (hence, the woman in the video saying that she has to commute into the city to do her work, rather than live close - she can’t afford it)

But the structure of work is enforced by a lot of things - absurdity of modernity, artificial constraints, and the silliness of sticking to things that don’t really work for the modern age.

Envisioning a Different Future

So going back to the video - there are a few components to it, but first, the response to it sucked! It was very much small people saying small things about their small interpretation of the world -

I don’t want to spend a lot of time discussing what people discuss, but every time you talk about a change in the workforce, it’s a typical response of “I can’t envision a world different than the one I inhabit personally, therefore, nothing is possible” or some variation of that.

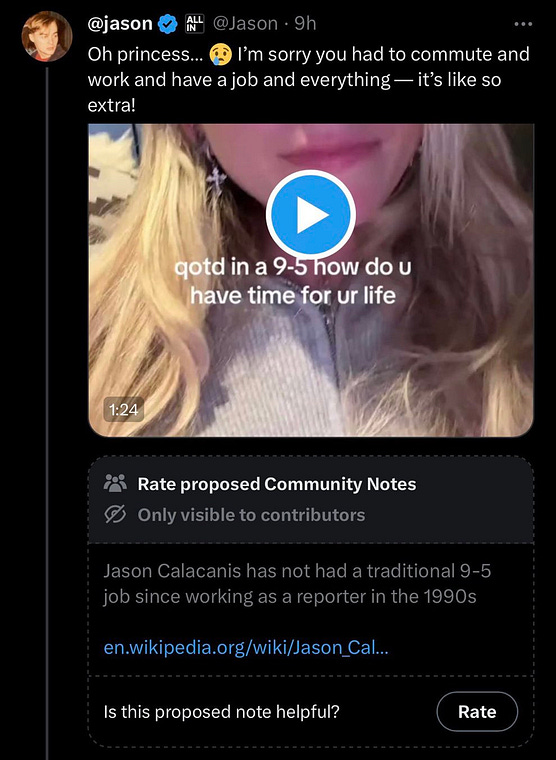

For example, Jason, a podcast host -

The pea-brained nature of those that can’t envision a future different than the present are the problem. We can’t punch down on people that are just trying to figure out the world. Adapting to the workforce is hard, and everyone knows that. Compassion goes a long way.

Why should we change it?

Some of the reasons to shift away from the structure of the 9-to-5 are biological, like circadian rhythms. People thrive at different times of day. Evening types and morning types and chronotypes are really important to how we work - and this structure doesn’t make room for that. People are different! They work differently.

But there are also social aspects to work too.

The ‘iron cage’ that Max Weber describes is poignant here - when modern life becomes bureaucratized (hiearchies! rules! procedures! powerpoints!), that feels dehumanizing. There is an element of artificiality to this, a maintenance of normalness where innovation could take place.

People can sense that! You can sense when the system is a relic from times past, versus something useful and good and beneficial. People can sense when change is necessary.

Finally, we should help new generations, not mock them. Adapting to the real world is scary and confusing, and because of the incentives of social media, people love to punch down rather than to pull up. I think one thing that was fascinating about the labor market movements of the 1800s was the collective nature of them. It was people saying ‘the only way that we are going to make this better is if we do it together’ which feels missing from today’s world.

Rather than ridicule new generations for questioning the status quo, we should empower them to redefine it. Just as workers in the 1800s united for better conditions, today's society should rally to make work more meaningful and humane.

Work as a structure doesn’t have to be how it was! Less than a hundred years ago, we made it so people had 8-hour work days. Things can be reinvented again, and they likely will be. The 4-day workweek, remote work, and async communication are already changing how we interact with each other.

Keynes thought that we would be working 15-hour weeks by the 21st century, which clearly, has not happened. That video was NOT about not wanting to work anymore. That video was about wanting to work differently, with flexibility and time to pursue other things (that, let’s be real, will probably lead to a new career path).

Basically, that young woman should be able to walk to work and have friends and have time to be a person! Her video was reasonable! Things don’t have to be how they always were. Instead of simply saying “life sucks, get over it” it’s time we say “life sucks, let’s do something about it.”

Thanks for reading.

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice or recommendation for any investment. The Content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.

I cannot emphasize enough how many things I am glossing over and how many rabbit holes there are too this. The labor movement of the latter half of the 1800s is truly fascinating, and should be studied deeply by anyone working (imo) because it gives such rich insight and perspective to where we are today

What ever happened to building a better world for our children? When did our society become so bitter that we perceive someone asking for a better future as entitled? It disappoints (but not surprises) me that people cannot get over the "I had it worse at one point so you should to" mentality.

Worker productivity has increased dramatically over the last few decades with the proliferation of technology, and it's incredibly disappointing that the benefits of that increased productivity has been reaped by the shareholders and management class while the expectation of the 9-5 workday is consistently pushed.

For many, their workday is orders of magnitudes more complex than that of the previous generations. Responsibilities that used to be managed by teams of people are now managed by a single person, while the expectation has grown such that a single person needs to output what used to be expected from a whole team. The ownership class reaps the double benefits of increased productivity with reduced labor cost, while the rest of us just gets more work.

In the past, technology promised us freedom and an equitable life. Instead, it has been used as a tool to bludgeon the working class into continuously producing more for the owners of the technology.

Kyla you really nailed it. I’m a retired engineering manager and gave my entire staff of 20 something’s the freedom to work when and where they wanted. Only requirement? Get the job done well and on time. They loved it but HR got wind of it and went absolutely apeshit (sorry about the language but it is accurate :-). Made them (salaried every one) click in at 8 and out at 5 with mandatory 1 hour lunch break. Then Covid happened. Got a call from a good HR person (they do exist) asking if I could send her a copy of my department’s WFH policy (that we wrote as a team) so the entire company of 20000 employees could use it. Happy days until Covid went away, then back to the clock!!!! WTF!!!! Retired and turned my management role over to a brilliant young person of 30 who is still fighting for the right for our team to be recognized as skilled talented responsible people, not just bodies carrying a badge with an access code. Again Kyla, you really nailed this.