Housing housing housing! Buy the book here (ch 10 is on housing) and don’t forget to leave a review! Thank you so much everyone.

We had a Fed meeting yesterday, where the Fed held rates steady and said “hey listen, we need to see more data but probably one cut this year maybe considering the election it’s all unknown everything is unknown in the vast expanse of the universe”. We also had a CPI (consumer price index) print, which showed that inflation was indeed slowing in most parts of the economy, but again we need to see more data. But - inflation was not slowing in housing. Never housing.

Part of that is a total disconnection between metrics and reality. The way that we measure shelter inflation is a bit fuzzy. Real time shelter inflation is actually… slowing. But there’s a lag. We measure housing inflation through two lenses:

Rents, which captures the actual rents paid by tenants for leased properties and changes when leases renew or tenants move

Owner’s equivalent rent (OER), which is a survey that asks what homeowners would rent their house for on the current market. It is a hypothetical value.

So there’s a bit of a time discrepancy here. It takes time for people to renew and to move, and therefore it takes time for price changes to show up in the shelter inflation metric. There’s also the strange nature of OER and what OER means and how it works, which is something for a different day.

But rent prices are going down. Shelter inflation, at least with real time data, is easing. We have added more new apartments in the first half of 2024 than we did over the past 30 years, according to Jay Parsons. New lease apartment rents are flat for the 11th straight month (!) - because we built more. And we are seeing more relief in certain housing markets, especially places like Austin, Texas.

But this isn’t the situation for everyone (my rent in a major U.S. city certainly has not gone down despite various leakages). That’s because housing is a very personal experience. It’s the ideal state, home ownership. It’s the one way we know to build wealth in the U.S. despite it not really… working. ($10,000 invested in equities in June 1974 would today be worth $2.4 million. If invested in housing, it would be worth $139,000 today.)

Despite that, the American Dream is predicated on the idea of owning a home.

The American Dream, as defined by James Truslow Adams, is “the dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement.” It’s no secret that the American Dream (at least the way Adams saw it) is no longer what it used to be.

Stability. Success. A sense of belonging. It’s the figurative - and literal - key to upward mobility and financial security. Most people design their lives around owning a home one day. And when you feel like you can’t achieve that - it doesn’t feel great.

So what’s going on in the housing market that makes it so difficult for people to own homes?

The Housing Market

A few months ago, I spoke with Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Wally Adeyemo about it (video version here and podcast version here). Because unfortunately (or fortunately), this is a problem that has to be solved by policy1. This has to be something that happens at the city or state or federal level. And luckily, many policies are being put into place to fix this.

Deputy Secretary Adeyemo: Ultimately, there is so much demand for housing in this country because since the financial crisis - basically, we've under invested in building housing. And the pandemic only created worse than that problem.

So yes, the pandemic did indeed worsen the housing crisis. There was a massive shift to remote work during the pandemic, which accounted for more than half of overall house price growth during that time, according to the San Francisco Federal Reserve. But the pandemic only exacerbated the issues that we were already facing.

If you’re trying to buy a home right now, you’re dealing with mortgage rates that are north of 6.5% (and they were like 2-3% a mere three years ago) and housing prices that have more than tripled since the early 1990s. Things have cooled off recently, but between December 2020 and December 2021, the median US home gained $52,000 in value and in eleven markets, grew by over $100,000 (!). That’s impossible to keep up with!

Even if you’re not trying to buy a home (like me) rental prices have risen as much or more than the cost of a home, moving at the fastest pace in 40 years. Between May 2021 and May 2022, rents went up by more than 15% to an average price of $2,000.

There is a reason that housing is 2/3rds or more of the CPI print! This is all problematic because housing is a foundational need. When younger people talk about how they experience the economy, that’s usually what they are referring to. Right now, a lot of people feel pretty poor because of the cost of shelter.

But there are also several lines of bifurcation.

There are the 90% of US homeowners that are locked into a fixed-rate mortgage, insulated from the impacts of monetary policy (and in my humble opinion, serving as a buffer against a recession) but also might feel like they don’t have any mobility to move away. They might feel ‘house-rich but cash-poor’.

Then, there are those who are facing the aforementioned mortgage rates, and feel like they have no mobility in general2.

Then there are those that swoop in with Scrooge McDuck bathtubs of cash - like the 70% of NYC homes that were purchased without a mortgage in the final quarter of 2023 - that make it hard to compete.

Then there are the almost 40% of homeowners with no mortgage at all - roughly 32 million people, mostly boomers.

We all know this. So how do we fix it? And this gets into the very confusing part of the housing market. What is a house? What role is it meant to play in our lives? This series of tweets probably captures the confusion better than any paragraph I could write -

As Derek Thompson wrote in his piece America’s Magical Thinking About Housing

In the U.S., our houses are meant to perform contrary roles in society: shelter for today and investment vehicle for tomorrow. This approach creates a kind of temporal disjunction around the housing market, where what appears sensible for one generation (Please, no more construction near me, it’s annoying and could hurt my property values!) is calamitous for the next (Wait, there’s nowhere near me for my children to live)

That’s the crux of the crisis. We have this inherent push and pull between housing being the wealth generation tool for the bottom 50% (getting into my favorite chart included below) and then being something that we are meant to live in and build community around.

So why can’t we build?

Well of course, it’s policies and regulations, NIMBYism, demographics, economic factors, and the inherent speculative nature of home ownership. It’s created this perfect storm of not-enough supply compounded by skyhigh mortgage rates due to the Federal Reserve raising rates in order to battle inflation.

NIMBYism

Housing is the foundation for our economic experience. There are some people who want more housing. Then there are those who don’t because it can interfere with their home value, their perception of their community, or whatever.

That’s NIMBYism. Not in my backyard. Aka keep that building away from me.

A lot of older homeowners will spend a lot of time blocking new development of housing for a variety of reasons. They also are staying in their homes a very long time (partially because eldercare is $10k a month). Empty-nest baby boomers own 28% of the nation’s large homes, while millennials with kids own just 14%. 56% of homeowners aged 60+ said they will never sell their home. There are immense tax breaks for seniors to stay in their homes, so it makes sense, but it’s not great.

And to be fair, the younger generations are getting into homes. Roughly 1 in 4 adult Gen Zers are homeowners, with many buying during the pandemic, according to Redfin. But you also have an increasing number of the younger generation living at home - another example of this bifurcation.

Climate Change

But it’s not just an age thing. Jerusalem Demsas wrote of how the YIMBYs and climate change activists were butting heads in Minneapolis, with the climate activists freaking out about development because of the environmental costs. And the environmentalists are wrong - wrong about trees and open space and water quality - because mostly, they just don’t want buildings around them. Demsas writes:

About 425,000 people currently live in Minneapolis. Despite all this [building of new homes], Butler’s wildflower sanctuary remains a public park, quiet proof that growth and preservation don’t have to be at odds. Even if triplexes replace single-family homes in nearby neighborhoods, from the sanctuary of the garden, no one would be able to tell.

Zoning

And then of course - Zoning.

Deputy Secretary Adeyemo: I think zoning is a nice way of putting it. I think one of the challenges we have is that many people don't want more housing in their community because they want to preserve the community the way that it looks at the moment. And part of our goal is to make the case to people that building more housing can be additive to the value of your community and improving it.

There are a lot of headwinds to building housing, and zoning is absolutely one of them. The Niskanen Center put together a brilliant paper outlining how we got here, pointing out anti-density regulations and the issues around mass transit. When we had a housing crisis in the 1880s, we started building elevators and rail rapid transit, enabling people to live upwards or travel in to the city. But then, backlash began, and as they write

Zoning emerged as the mechanism to control not only unwanted economic activity - for example, the defensible purpose of limiting areas in which industry could settle - but also unwanted neighbors.

More than 90% of residential land in Los Angeles is zoned for single-family, making it very hard to build multifamily residences there. Minimum lot sizes, height restrictions, parking requirements, even things like leaving space for our gigantic fire trucks to turn make it hard to build3. Then the politics get messy, like the city of San Francisco voting to downzone - making it even harder to build homes. We need upzoning.

As Maltman and Ryan (2024) found in their working paper Going it Alone: The Impact of Upzoning on Housing Construction in Lower Hutt upzoning can stimulate housing supply. That’s what we saw in Austin Texas, a gem for zoning reform.

Austin, Texas is building enough housing - and because of that, rents went down 7% in their city. They upzoned 170 acres to allow buildings up to 350-420 feet, ended minimum parking requirements, eliminated single family zoning, and allowed three homes on each residential lot (allowing for duplexes and triplexes), allowing for tiny homes and accessory dwelling units.

This is also what we could see in Burlington, Vermont where they just totally reformed their zoning, allowing for two buildings on every parcel and for 4-plexes everywhere.

However, zoning is still problematic in most places. Housing codes can also be a headache, specifying minimum off-street parking, minimum lot size, surface coverage, a mix of bedrooms, curb cuts, kitchen ventilation - which is great, but ends up preventing more growth than encouraging it. For example, according to Aaron Lubeck, a lot of suburban America is codified to:

2 25’ setbacks

2 5’ sidewalks

2 5’ planter strips

36’ curb-to-curb

9'- 22' side setbacks

30% impervious surface max

FAR < .25

Density <8 du/acre

2 off-street parking spaces per unit

minimum lot width 75'

minimum lot size > 10,000sf

The permitting process can be an absolute racket too. There was a developer in Boston who gave a $750,000 ‘donation’ to a neighborhood association, presumably so they could build out a new development in the neighborhood.

The compounded effect of housing codes and restrictive zoning and racketeering and cities that aren’t designed for people ends up creating a shortage of housing - because you can build but it’s hard.

But Yet We Build

Just because something is hard doesn’t mean we can’t do it.

Through Money

Deputy Secretary Adeyemo: One of the things that the President has us focused on is increasing the supply of housing because that's one of the best ways to reduce the cost for all Americans. So at the Treasury, one of the things that we have is the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, which is one of the ways we help incentivize the creation of housing. And the President has proposed that we use the Low Income Housing Tax Credit to create 1.2 million additional units of housing all over the country that will help bring down the cost of housing, not just for the people who get those new units, but for everybody.

The Low Income Housing Tax Credit provides tax credits to developers for eligible projects to incentivize building affordable housing. It is the largest source of Federal Support for the construction and rehabilitation of affordable rental housing across the country, building about 3.8 million units since 1986. There is a new income-averaging rule allowing flexibility around mixed income developments, which is important because we need all types of housing.

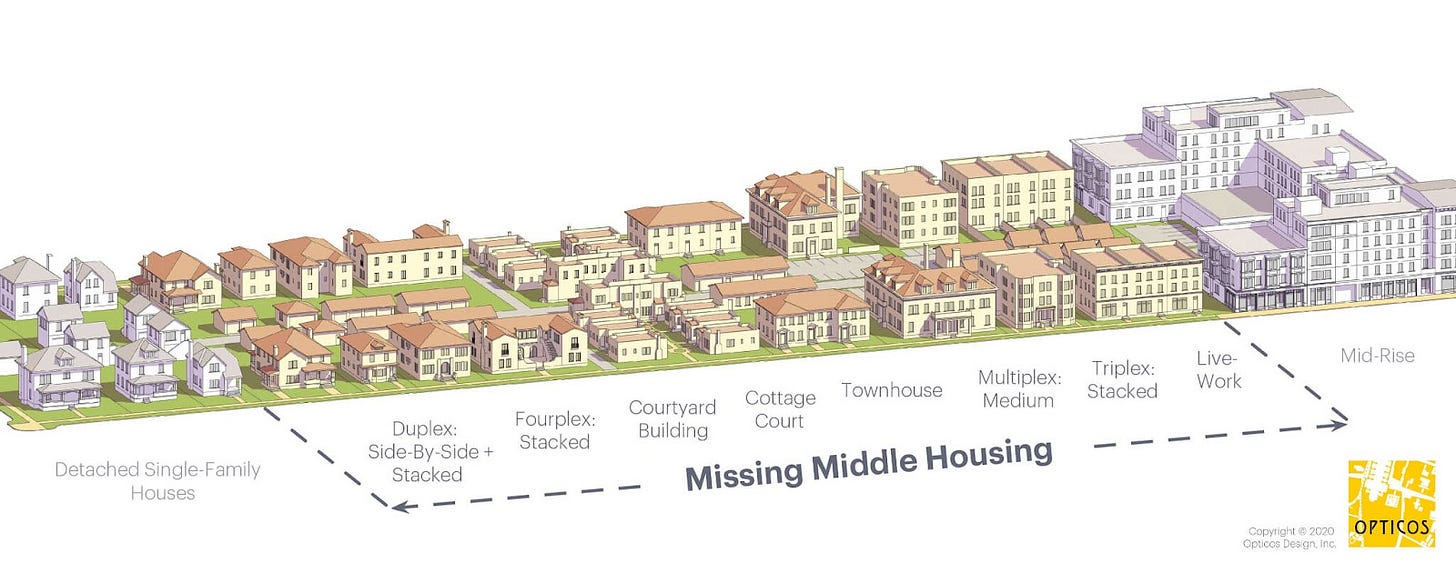

Housing affordability is not just ‘build more homes’ - it’s build more everything. We need 1.86M new homes per year into 2033 in order to keep up with demand. We need more triplexes and duplexes. There is a missing middle in housing - not enough townhomes, duplexes, triplexes, etc. We could create millions of homes just by turning some single family homes into these.

Building all types of homes is important.

And this gets into the idea of filtering, or that building even luxury housing benefits everyone because the rich person moves into the luxury housing, leaving space for someone else, and so on and so forth. Kate Pennington of UC Berkeley found that ‘rents fall by 2% for parcels within 100m of new construction’ and the risk of displacement is lowered too, improving overall neighborhood quality. Stephen Hoskins has put together an incredible treasure trove of research papers highlighting papers from Liang & Kindström (2023) and Mast (2023) that both conclude -

“Building new homes, even expensive ones, leads to important trickle-down effects. Thus, stimulating the supply of new homes is a viable approach to improving the housing situation of the poor”

A study by the Minneapolis Federal Reserve found -

New units help keep current prices down for everyone by opening up new opportunities for low- and moderate-income renters over a few short years through a chain of residential moves.

Through Grants

Deputy Secretary Adeyemo: And to [encourage building] we've put together grants for local communities that are willing to take on some of those interests and to advance building more housing in communities and changing the rules to make that possible. Ultimately, the way we're going to solve this problem is we're going to have to do a community-by-community, which is hard. We think that the thing we can do in the federal government is create financial incentives that help communities that are trying to do the right thing.

And local communities are taking this on.

Montgomery County, Maryland is a great example of this. They decided to start bidding on projects because they realized that while developers might need 20% profits, the government sure doesn’t. And it’s not like these projects are being produced at a loss - they generate money.

So they’ve built a 268-unit mixed-income, mixed-use construction project financed through a $100m fund created by the county government. The fund partners with private developers, offering them large discounts, which most developers are pretty happy about.

That is followed by a 463-unit complex for seniors and families and a 415-unit complex across the street. This is an application of the low-income housing tax credit.

There are also things like the Innovation Fund for Housing Expansion which is a $20b competitive grant fund that would “support the construction of affordable multifamily rental units; incentivize local actions to remove unnecessary barriers to housing development; pilot innovative models to increase the production of affordable and workforce rental housing; and spur the construction of new starter homes for middle-class families.”

Through the Conversion

There are also initiatives like converting commercial properties to residential. $35b has been allocated toward this, but none has been used yet due to endless permitting processes and environmental review. And commercial to residential is hard, but it’s possible - and can even be cheaper. According to Commerical Observor

Construction costs for a ground-up residential development in Manhattan could run $500 to $600 a square foot, per Chilelli, while a conversion generally costs between $300 and $400 per square foot. Pearl House cost close to $325 a square foot, he said.

Deputy Secretary Adeyemo: I agree with you that ultimately, where possible converting commercial real estate into residential housing makes a lot of sense. They're like practical issues, some of them being that there's just not enough bathrooms in a commercial real estate bill to turn it into apartment buildings, but then there are local political issues where many of these local communities would rather try and hold on to commercial real estate because of the tax revenues rather than turn it into housing

Commercial real estate is a problem within itself. But it affects the value that businesses get from building more housing - because this isn’t just an individual issue.

This is More than Just Your House

Deputy Secretary Adeyemo: One of the part of my job is talking to CEOs and small business and large business leaders. And what they tell me is that it's hard for them to find employees. And when they find employees, it's hard for those employees to afford housing near the places where they want them to work. So housing isn't only a challenge for individuals. It's a challenge for businesses in our country too.

There are also many jobs in building homes and ensuring that the next generation of construction workers is trained.

Deputy Secretary Adeyemo: Traditionally, I think the federal government spends maybe somewhere in the neighborhood of $1 billion on an annual basis on workforce training. Because the American Rescue Plan over the course of the last three years, we spent $12. 8 additional billion on workforce training to help people get the skills they need to do the jobs that are need in the economy… So the key for us is making sure that we invest in the training so that we have the employees to not only build housing, but to build all the things that the economy needs. And because of the money that has been been invested in workforce training by communities, but also by the federal government, I think we're better positioned to do that.

But ultimately, finding more people to do these jobs is going to be a critical path, a critical thing that we have to do to be able to succeed at building more housing. The housing crisis impacts the entire economy - it’s not just individual homes and invidiual lots, these are communities.

City Design

Deputy Secretary Adeyemo: The idea that people have had to live further away and commute further to come to work has huge costs for not only our climate but also our communities. That hour and a half drive that could be a 15—to 20-minute commute is the difference between being able to coach Little League and instead sitting in the car, just from the standpoint of community impact. But it also comes at a huge cost to our country's infrastructure. And that's partially why we're very focused on trying to build more housing, multifamily and single-family, that is close to transportation hubs. So subways and bus lines are being built to reduce the impact on the planet of the fact that right now, too many Americans are not able to afford to live near their place of work.

That is an extreme cost of infrastructure per linear foot, something that Governor Doug Burgum highlighted in a recent talk.

Zoning came during the Industrial Revolution… It was a one dimensional map. And you draw it out and say everyone, all these four things have got to be separate. That was great for the people that have built roads and it's great for the car companies… We built cities all over America that are designed for automobiles and not designed for people…. So I think one of the things that we have to look at as a country, our housing costs are high, in part because of the way that we've designed our cities… We've got to get the coffee shop, the barber shop and law firms back into residential neighborhoods in ways that can help lower the cost and create services where you don't need a car for everything.

We have to redesign our cities to be people-centric. The automobile has as much space than the average family unit. We love our cars, so that probably isn’t going away, but walkable cities, alternative transit options, safe bike lanes - the cities must be designed around people to work long term.

Rethinking Housing

Many policies are being implemented to fix the housing crisis. But we have all these variables—status anxiety, the dual role of housing, housing as a retirement account, wealth inequality, the constraints on economic growth and labor mobility, longer commute times and sprawl, and lack of innovation.

In Negative Yield New York, Alex Yablon wrote about the importance of cities being accessible to those just starting out and how policies like the ones we discussed can help fix this.

But once the city gets access to extremely low-interest credit, it could also invest in massive amounts of new housing to drive down the cost of living as well as cultural infrastructure: the city could create new studios, rehearsal spaces, galleries, and performance venues to ensure that its vital artistic economy can thrive alongside other sectors that have increasingly crowded out the underground… There's a deep sense in which freedom is achieved through the basics of life being extremely plentiful and cheap. When we don't further that, people's lives become less free.

Of course some people will mutter, “But the world is unfair, how can you say everyone should have a place to live?” Of course the world is unfair, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to make it better. As Barbara Alice Mann of the University of Toledo wrote,

“Westerners are fond of the saying ‘Life isn’t fair.’ Then, they end in snide triumph: ‘So get used to it!’ What a cruel, sadistic notion to revel in!”

Fairness is subjective, and the balance of equality and equity is a delicate dance. But in regard to housing, supply has always been the problem. The core fact of the housing issue is that we need more of it, but there needs to be an evolution of regulations in order to make that happen.

It is the housing theory of everything. Lowering housing costs creates many downstream benefits and frees up so much capital. There was a Bloomberg CityLab piece highlighting this -

Instead of driving more innovation and growth, the bounty from today’s knowledge economy is instead diverted into rising land costs, real estate prices and housing values. The result is that working- and middle-class Americans are forced to devote ever-larger shares of their hard-earned money for shelter. The central contradiction of capitalism today is that a huge share of its productive surplus ends up being plowed back into dirt.

A lot of people say ‘it's time to build’ with startups. And it's a cliche at this point, almost contradictory, because it’s focused so much on bits instead of atoms, to borrow Thiel’s phrasing.

But here, it applies well—in reality, allowing more housing would ultimately allow more people to build. We need atoms. With all due respect, AI might be able to upzone local communities and fashion triplexes sometime in the future, but it’s not doing that now. More housing would remove our social and structural isolation, connect us to each other, and make people have hope in the American Dream again.

According to the Census Bureau, the percentage of Americans who move each year keeps falling, with a lowest-on-record metric of 7.8% of US residents saying that they lived in a different place than they had a year earlier (or it might be a measurement error)

The book Paved Paradise is an excellent read on how parking has shaped the U.S.

Agree with the premise but is it a given that ownership of one's home is supposed to be a route to wealth building? Pretty illiquid path for such. Maybe if we don't see it as an investment we would all be better off.

Funnily enough, an ever greater share of rents being captured by landlords was the same thing the OG political economists like Smith and Ricardo were concerned about. Plus ça change…