Zero-sum Thinking and the Labor Market

is college worth it? and other questions about the state of things

Good morning from Aspen, Colorado!

Last week, I joined Jon Stewart on the Daily Show (!!) to talk about how we might think differently about the economy. This week, I spoke at the Aspen Institute about what it actually feels like for young people trying to live in said economy. Both events were extraordinarily interesting and brought up two main questions:

What is happening to the labor market right now?

What do we do about it?

The path of predictable progress is largely gone - the ROI on a college education is unclear, buying a house (if you don’t have vast family wealth1) feels incredibly out of reach, the rate of getting married and having kids has fallen - combine all that with the push and pull of the transformational power of AI and it makes it all that much more uncertain.

And of course, that framework is nothing new to anyone at this point. But in this piece, I want to examine the labor market as it actually functions today - less like a ladder, more like a slot machine - and the zero-sum logic that’s emerged in response.

The Rise of Zero-Sum Thinking

In 1957, the Soviet launch of Sputnik triggered a huge US response. It led to 3x funding for science education, created NASA and DARPA, and created massive investment in talent and infrastructure (and optimism). The US looked at a challenge and said: We can build our way out of this.

As economist Alex Tabarrok pointed out in his piece about the Sputnik moment, that kind of mobilization didn’t happen in 2024 when China’s2 DeepSeek AI surpassed OpenAI’s GPT-4. The US retreated instead of rallying. We looked at a challenge and say: They must be stealing from us.

This is a shift in how we understand problems and solutions. As Alex highlighted, research shows we're developing what economists call zero-sum thinking, or the belief that my success requires your failure, that wealth and opportunity are fixed pies to be divided rather than expanded. As Alex explains, zero-sum thinkers “see society as unjust, distrust their fellow citizens and societal institutions, espouse more populist attitudes, and disengage from potentially beneficial interactions.” It’s a form of despair that arises during times of economic uncertainty.

Platforms like Jubilee, where extremists debate for views, have become arenas for this despair. Mehdi Hasan recently debated 20 Far-Right conservatives in one episode, most of whom argued with emotion over data (as is common on both sides, Asimov’s cult of ignorance in action). It was rage as algorithmic fuel - Imani Barbarin called it the “memefication of politics”, which it largely is because it all becomes spectacle. This performative anger is a direct feature of the zero-sum mindset.

And at scale, this type of mindset can lead to a zero-sum trap as Tabarrok points out

The more people believe that wealth, status, and well-being are zero-sum, the more they back policies that make the world zero-sum.

This is what is going on right now. Putting aside however you might feel about the current administration’s policies, (1) trade wars (2) deportation quotas and (3) holding pens like “Alligator Alcatraz”3 and (4) gutting our science are all extraordinarily zero-sum approaches to building our future, especially when compared to the Sputnik moment of not so long ago.

The Sputnik generation organized society around creating abundance, a “creation” phase of infrastructure. They built universities, highways, suburbs, and systems that expanded opportunity. When they faced the Soviet challenge, they tried to make America richer rather than make the Soviets poorer. There was a belief in a positive-sum future, that everyone could grow together.

It’s the reverse now. We are in the “management” phase of infrastructure. Rather than viewing immigration as demand expansion and a chance for the pie to grow, we treat it as a scapegoat for wider systemic failures. Immigrants become a proxy war for how we think about identity, who deserves what4 and people on Jubilee argue over who gets the smaller pie.

In this management phase, we've watched student loans turn universities into profit centers. We've seen healthcare become a financialized industry. We've witnessed housing become an asset class for investors rather than, you know, homes for people to live in. Everything feels like it's being optimized for someone else's profit rather than expanded for everyone's benefit. And so young people (and everyone else living through this moment) have been taught to think in zero-sum redistribution rather than positive-sum creation.

Can we reverse it? How can we build a Sputnik moment again? It begins by tackling the very real challenges in our labor market.

The Labor Force

There are two important themes to understand about the labor market right now, as documented by Will Raderman in a guest post for EmployAmerica and John Burn Murdoch of the FT:

College graduates are struggling. “Since 2018, the unemployment rate of recent college graduates has generally been higher than the rest of the labor force.” - Will

Young men are struggling the most. “The rise in graduate joblessness is concentrated almost entirely among young American men.” - John

Both John and Will are quick to point out that the rise joblessness isn’t due to AI but rather

Sectoral changes, like the shift to a healthcare-oriented jobs which tend to be dominated by women

Supply and demand - there are a lot more college grads than there used to be

A softening of the overall labor market in our current slow-to-hire, slow-to-fire environment5 and

The techcession of the past few years, with higher rates striking reality into the heart of many of a vaporware company.

So, to repeat, recent college graduates now have higher unemployment rates than the overall workforce. This isn't supposed to happen. For decades, a degree was economic insurance - graduates always found work faster than everyone else. That’s what you pay for.

Is College Worth It?

But we're asking the wrong question entirely about college. Instead of 'Is college worth it?' we should be asking 'Which parts of college are working, and what does that tell us about the future?'

The math is brutal for most graduates. Boomers could trade 4 years of college for 40 years of middle-class security (more or less). Today's 25-year-old faces a negative net-present-value on that same deal. When the fundamental economic bargain breaks down, it flips everything - your discount rate, your risk tolerance, your entire worldview, again, leading to zero-sum beliefs.

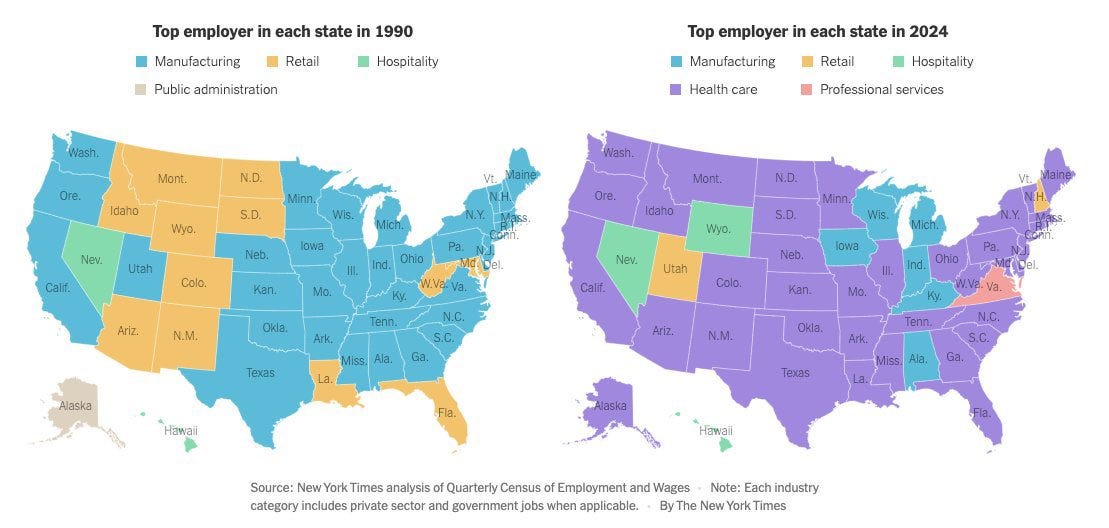

But some parts of college are working, especially those that prepare for people to work in the healthcare sector as mentioned earlier. Look at these maps! In the 1990s, the top employer in each state was manufacturing. In 2024, it’s healthcare. That’s a different economy.

We are a maintenance economy, rather than a creation economy.

There are two important points to make here:

Women are succeeding in this new economy: A lot of these healthcare jobs are going to women. As John reports, “almost 50,000 of the 135,000 additional jobs filled by young women graduates in the past year were in America’s healthcare sector — more than double the total number of additional jobs going to graduate men across all sectors over the same period.” This is partly because by 2030, 1 in 5 adults in the US will be over the age of 65 and partly because we are a rather sick and unhealthy country.

Men are not: One solution floated to help men out is to bring manufacturing jobs back, a revival of the 1990s. The problem is that there are 500,000 unfilled manufacturing jobs open right now, so maybe we should focus on filling those with proper investment in training, rather than mining coal again.

These shifts underscore a fundamental truth: the economy has changed, jobs have changed. Jobs have changed. Colleges have to change. Training has to change. This is about aligning our education system with the actual structure of today’s economy. A real Sputnik moment wouldn’t just yell bring the jobs back! It would ask: what kind of future are we preparing people for?

The Hiring Process

And this is about how people get hired too, not just the jobs themselves.

Derek Thompson also wrote about this phenomenon a few weeks ago, noting that AI has essentially turned job applications into an arms race. Humans send thousands of tailored AI-generated resumes at job postings, companies deploy bots to screen them creating total vacuum of bots talking to each other (similar to how bots are enjoying the AI generated music on Spotify). It turns it into a numbers game.

Back in 2019, I applied to over 150 jobs when I graduated Western Kentucky University. LinkedIn had their little QuickApply feature, but I wrote so many essays, did many projects, and endless interviews. The entire process made me better, but I was rejected from most of the jobs.

I had a 4.0 GPA, was valedictorian with three majors, worked three jobs for most of my time at university, sold cars, ran D1 Track and Field for a year, and yet, I only got into my first job because the recruiter and some people at the company took a big chance on me (and I only got there because they had a blind resume process where they hid the school. Says a lot about a lot).

The only reason I got my chance - a truly lucky break - was because people bet on me. A computer would have instantly rejected me because I didn’t meet some arbitrary qualification. AI has spurred us right into the depths of what David Brooks calls the rejected generation - endless nos from platforms that are meant to serve as human interfaces (slot machine grabs across dating, investing, and now jobs), but really end up dehumanizing the whole process.

This is why young people are applying to 1,000 jobs - (1) to get one and (2) they're desperately seeking algorithmic validation to replace the human validation that the system has removed. The job search used to be a proving ground of sorts. The job search becoming algorithmic removes the human validation that made rejection bearable. When a human rejects you, you can tell yourself they didn't "get" you. When an algorithm rejects you, it feels like objective proof that you're insufficient. No wonder they're developing zero-sum mindsets and political radicalization.

This game fosters a dangerous proficiency illusion too, where both applicants (through AI-generated resumes designed to 'beat the bot') and companies (through AI screening that prioritizes keywords over skill) are optimizing for algorithmic compatibility rather than genuine human capability. It’s a performative dance for the machine, potentially eroding the very skills critical thinking and problem-solving needed for future human capital.

The Casino Economy

This is the casino economy in action. Again, just like dating apps and meme stock trading, the job market has created the illusion of abundance by replacing meaningful friction with meaningless volume. It has become a dopamonster, to borrow Scott Galloway’s word. More applications, more swipes, more trades - but every extra option raises the noise-to-signal ratio, making the median outcome worse for everyone.

A job market that once rewarded persistence now punishes it. A dating market that once rewarded genuine connection now atomizes it. Markets that once rewarded research and patience (sort of) now gamifies everything into day-trading dopamine hits. When the only lever left is 'push more buttons,' the rational response becomes zero-sum cynicism.

We've turned job hunting into a lottery where you buy as many tickets as possible and pray one hits and it is destroying our belief in meritocracy itself. When getting a job feels like winning the lottery6, what happens to the 'hard work pays off' narrative that held American society together? It creates the kind of thinking that feeds zero-sum thinking: “if I can only win by gaming a rigged system, then the system itself must be fundamentally unjust.”

In a true market, skill creates value. The casino economy is about simulated fairness masking an imbalance. Everyone feels like they could win - and this structure thrives on hope just long enough to drain it.

What Next?

The zero-sum trap is reinforced by institutions that feel broken, bogged down by the "management phase" of infrastructure where inertia takes over innovation. Systems that work are what make belief possible again.

Reclaiming Capacity

As Robert Gordon and Jennifer Pahlka wrote in The New York Times, a new playbook is emerging in “intelligent disruption”, and they highlight cities that are making sure “that our public institutions have the right people doing the right work” rather than “across-the-board cuts to programs and raise fees and maybe taxes”.

In Denver, Mayor Mike Johnston got rid of antiquated seniority-based layoff rules, instead empowering managers to weigh performance and ability. It’s never good when anyone gets laid off. But instead of the typical last to hire, first to fire, this playbook is focused on ensuring the public has the right people doing the right work, rather than simply preserving obsolete positions.

San Francisco's City Attorney, David Chiu, used AI to identify over 500 outdated requirements for staff reports (the thing that leads to public toilets costing $1.7 million.) The goal is to eliminate excessive regulation. Another thing that Pahlka and Gordon focus on is using technology smartly - New Jersey has trained their employees to use AI, rather than banning it entirely.

Redefining Prosperity

Another piece offered some food for thought (and threads of hope). Jonathan Rauch and Peter Wehner wrote on how to rewire this infrastructure of opportunity, addressing young people’s economic concerns, interviewing 19 democrats across a range of views. The main takeaway I got from their article is that Democrats need to (1) build more (2) talk normal (move past the memefication of politics and focus even more on shared, tangible realities and problems) (3) put forward proposals like building vocational-technical high schools and chartering new cities.

Affordability is the #1 issue.

Many young people supported Trump in the election because they believed he would protect the economy. It’s also why Mamdani won. Faced with rising inflation, a broken labor market, and deep frustration over student debt and housing costs, Trump’s narrative offered clarity: he promised lower prices, more jobs, and a return to order.

But by July, that promise has largely unraveled. His tariffs have backfired, shouldered by the consumer, raising the cost of goods like clothes and electronics, as the WSJ documents in their piece on Amazon hiking prices on most essential goods by 5% over the past 4 months.

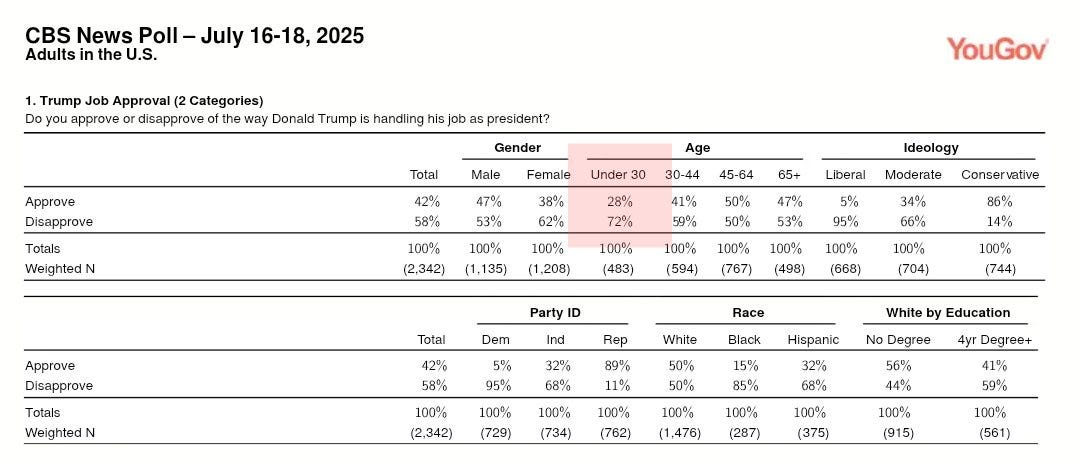

For a generation that experiences policy in real time through TikToks about layoffs, evictions, and AI ghosting, the disconnect was immediate. His approval rating among those aged 18-29 has fallen by 44 points, with 72% disapproving. I am not sure if they will flip back. People voted for him to make things real again7, and instead he’s very much added to the fog rather than lifting it.

Some people seem to think that young people went further right - that “Trump isn’t conservative enough”. That doesn’t show up in the data either, with almost 2/3rds of young people thinking he has been too tough on immigration. But people just want things to be affordable again.

We’ve seen the predictable paths vanish, replaced by a zero-sum casino economy where algorithms mediate our worth and artificial scarcity is optimized for someone else’s profit. This mindset, amplified by a fractured political landscape, threatens to trap us in a cycle of anger, distrust, and disengagement. It's a stark reversal from the Sputnik generation's belief in positive-sum creation, where national challenges sparked mass investment in human capital and an expanding pie for all.

Everyone seemingly agrees on the path forward - reduce regulation, build things, invest in students and their outcomes, and it’s happening at the local level. Platforms should have some responsibility too, ideally. Tech companies8 are increasingly the Fourth estate of government as shadow policymakers due to their power in disseminating information, and we really have to treat it as such.

The young people applying to 1,000 jobs and getting rejected by algorithms are canaries in the coal mine of a society that's forgotten how to create rather than extract - and they've been trained to expect systems that work for them, not against them. If we can equip them to build for creation instead, we might just find our Sputnik moment yet.

Thanks for reading!

There’s about $84T changing hands over the next decade, which could change a lot of things structurally - or it could maintain the status quo.

In fact, China is sitting back and just watching - they are (1) boosting trade with other countries (2) organizing allies around itself and (3) building as the US destroys itself

“Each bed at the detention camp is expected to cost $245 a day — roughly the price of one night this week at the Intercontinental Miami hotel. Right now, Florida taxpayers are footing the bill.” according to the Miami Herald

As documented extensively by CATO and the Economic Innovation Group

Companies are being more cautious in both hiring and firing due to economic uncertainty

Another strange example of this that I couldn’t quite find the wording for - people are becoming ICE officers to parlay their wages into buying Airbnbs.

This isn’t why everyone voted for him - many voted for him to remove immigrants, to start trade wars, to gut labor regulation, and he has met many of those promises. But he has not at all improved the economy.

Right now, “the administration hopes to use the threat of tariffs and access to the U.S. economy to stop multiple countries from imposing new taxes, regulations and tariffs on American tech companies and their products” as reported by the WSJ so this isn’t happening anytime soon

So many sharp -- and actionable -- insights here but this one struck me as being particularly important: "In this management phase, we've watched student loans turn universities into profit centers. We've seen healthcare become a financialized industry. We've witnessed housing become an asset class for investors rather than, you know, homes for people to live in. Everything feels like it's being optimized for someone else's profit rather than expanded for everyone's benefit."

"[T]hey are canaries in the coal mine of a society that's forgotten how to create rather than extract ...."

I would argue that it's not forgetfulness. It's design. The wealthiest have decided that extraction and maintaining their own position in the hierarchy are more to their benefit than creation (and especially creative destruction).

I would argue that this is the fundamental truth that explains so much of the details listed in the article above it.