Gen Z and the End of Predictable Progress

how AI, volatility, and changing institutions are shaping young people's economic reality

Generations are tricky to generalize as individual experiences are very different, especially in a country as big as the US. Still, broad patterns can offer insights into how technology and economic shifts shape generational identity and opportunity.

The Demographic Split

I’ve spent the last eight-ish months traveling and talking about the book, visiting 20+ states while talking with leaders like Wally Adeyemo, Mary Daly, Austan Goolsbee, and the Committee on Ways and Means, while speaking at conferences like skuCon, Exchange ETF, and the Council of Economics Education, and at universities like Harvard, MIT, Western Kentucky University, Notre Dame, University of San Diego, and many more (it’s been a great few months for my travel points).

The goal of this essay is to take the lessons I’ve learned on the road and explore three key elements: how Gen Z sees the world, how this worldview affects their political and economic choices, and what this means for the future of our institutions. (This essay is quite long so it could be cut off in your inbox and there are many footnotes)

Key Takeaways:

Gen Z faces a double disruption: AI-driven technological change and institutional instability

Three distinct Gen Z cohorts have emerged, each with different relationships to digital reality

A version of the barbell strategy is splitting career paths between "safety seekers" and "digital gamblers"

Our fiscal reality is quite stark right now, and that is shaping how young people see opportunities

Young People Are the Future

Young people are the future. There’s really no way around it unless we robotify everyone or something. Lots of people don’t like Young People and are frustrated by their shortcomings. A lot of it is generational cycling - every older generation thinks the younger generation doesn’t work hard enough, doesn’t care enough, etc. And maybe the smartphones have gigafried everyone. Something has. Lots of people far smarter than me have written about Gen Z and technology, particularly Jean Twenge and Jonathan Haidt.

But young people are facing a double disruption - (1) technological creative destruction in the form of AI combined with (some form of) political creative destruction in the form of the Trump administration. When I talk to young people from New York or Louisiana or Tennessee or California or DC or Indiana or Massachusetts about their futures, they're worried about finding jobs now, sure, but they're also extremely worried about whether or not the whole concept of a "career" as we know it will exist in five years. So in this piece, I want to talk about:

How younger people experience the economy, especially in the age of technology and AI and perhaps an evolving government (and changing social contracts…?)

How it's reshaping who they become.

This present moment of the combination of artificial intelligence and algorithmic systems have created a massive fundamental reckoning in the form of entirely new relationships between technology, economic opportunity, and personal identity.1

The Gen Z Cohorts

Gen Z is the age group born between 1997 - 2012 (or so). I am an elderly Gen Z (I am 27) and graduated from college in 2019 - right into the pandemic. PRRI has an excellent paper on Gen Z’s relationship with the world, highlighting their lack of trust in institutions and the challenges they have in making social connections. They will be about 25% of the electorate by 2030.

Each Generation is ~15 years in range, which is extremely wide. A 44 year old millennial has a very different life than a 29 year old millennial but they are both “millennials”. We all know that is fraught with error, but grouping is useful for frameworks and broad sweeping generalizations, like I am about to do.

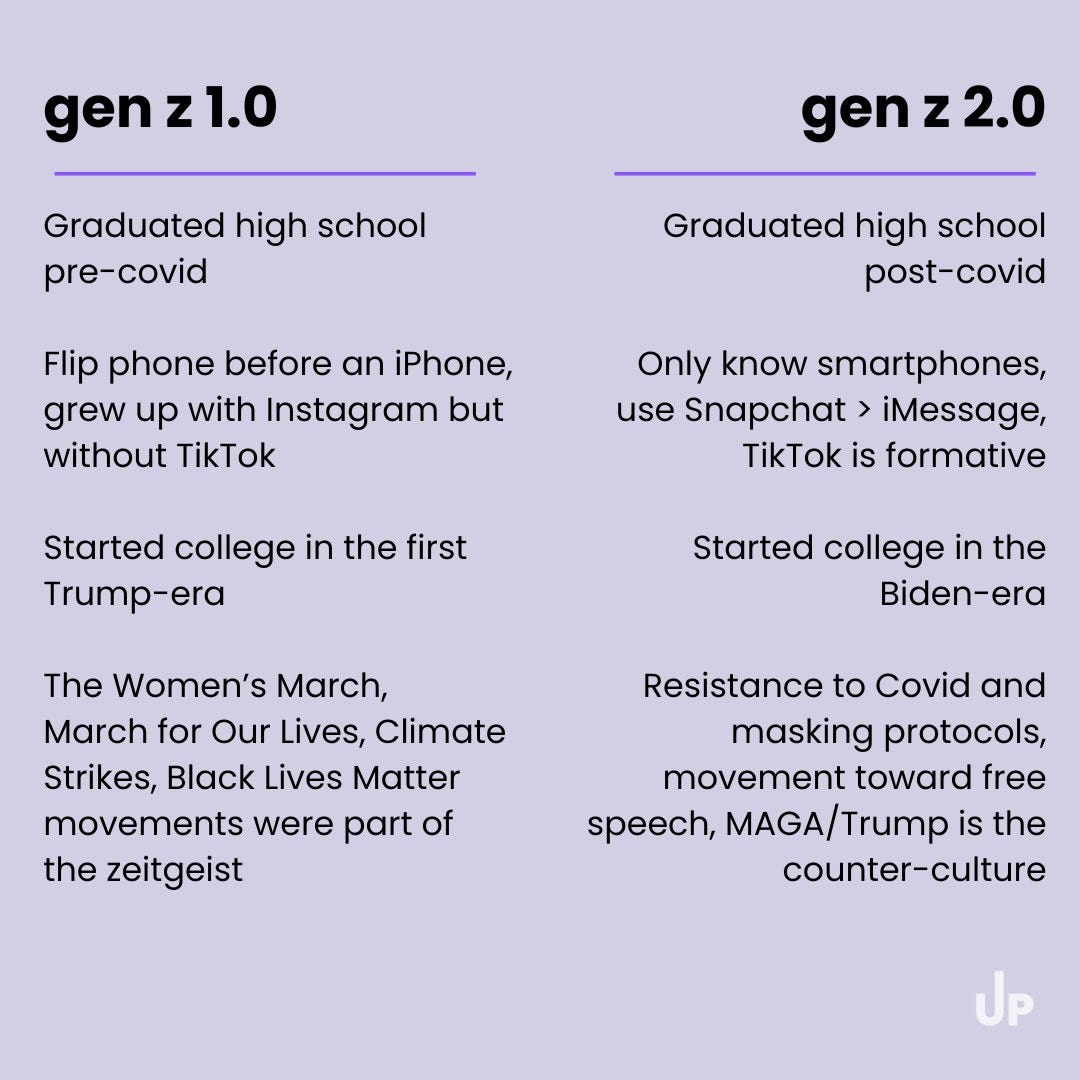

There was a ‘two Gen Zs’ graphic floating around on Twitter the other day from Rachel Janfaza. I don’t really agree with the whole thing (hence, newsletter) but it raises some important questions.

Rachel’s graphic says that the Covid experience has split the generation in half, shaping how they interact with the world. And Covid is a good demarcation between the generations, with it having a profound impacts on development and literacy. But the Covid experience was also shaped by technology, right?

Isolation: Smart phones and AI are fundamentally reshaping Gen Z’s understanding of the economy and wealth built in it and who they become in the process. I think everything in Rachel’s graphic boils down to (1) the isolation that the pandemic caused and the role of technology and (2) how that isolation and technology formed how we interact with the economy.

Social media: When TikTok/the creator economy started gaining traction in the late 2010s, it wasn’t really a ‘career’ yet. There were YouTubers and professional newsletter writers, but Covid created the moment that truly anyone could be a star and reshaped how the younger generations think about work (especially in post-pandemic era inflation and price pressures).

When a main path to financial security comes through the algorithmic gods rather than institutional advancement (like when a single viral TikTok can generate more income than a year of professional work) it fundamentally changes how people view everything from education to social structures to political systems that they’re apart of.

The 3 Gen Z’s

I think there are three groups of Gen Z, all of whom have fundamentally different relationships to digital reality.

Gen Z 1.0: The Bridge Generation: This group watched the digital transformation happen in real-time, experiencing both the analog and internet worlds during formative years. They might view technology as a tool rather than an environment. They're young enough to navigate digital spaces fluently but old enough to remember alternatives. They (myself included) entered the workforce during Covid and might have severe workplace interaction gaps because they missed out on formative time during their early years.

Gen Z 1.5: The Covid Cohort: This group hit major life milestones during a global pandemic. They entered college under Trump but graduated under Biden. This group has a particularly complex relationship with institutions. They watched traditional systems bend and break in real-time during Covid, while simultaneously seeing how digital infrastructure kept society functioning.

Gen Z 2.0: The Digital Natives: This is the first group that will be graduate into the new digital economy. This group has never known a world without smartphones. To them, social media could be another layer of reality. Their understanding of economic opportunity is completely different from their older peers.

Think about AI. Gen Z 2.0 will have to see it as simply the water they swim in, whereas Gen Z 1.0 will remember a time of pre-digital stability. These are different relationships with digital reality, and these differences show up in everything from career choices to political alignments to basic assumptions about how the world works. Jean Twenge has a good summary of how work has changed for the younger generations since Covid, highlighting post-pandemic burnout, reset of priorities when faced with death, a strong job market, and broad pessimism as a generation.

But to understand why these different groups of Gen Z respond so differently to our current moment, we need to examine the fundamental framework through which they view reality.

How They See the World

That’s the field that young people are playing in at the moment, and it creates a rocky economic landscape. It’s FAFOnomics (embracing or creating chaos as a response to systemic instability) and it’s happening at the individual level too. They’re responding rationally to a world where traditional "safe" choices feel increasingly risky. There’s a feedback loop.

Technology → Economics Every new platform creates its own economy. TikTok is a wealth generation machine that can turn attention into currency. When someone can make more from one viral video than their parent's monthly salary, it fundamentally reshapes how we understand value creation, especially in an era of dismantling government and changing workforces.

Economics → Identity Your relationship with money can become about how you see yourself in the world. The online world creates distinct tribes and each group can develop its own culture, internal language, and worldview.

Identity → Technology How we see ourselves shapes how we use technology. Gen Z 2.0 understands reality through a digital-first lens. Their identity formation happens through and with technology.

Think about crypto culture as an example:

Technology enables new forms of value exchange, which creates new economic possibilities so people build identities around these possibilities and these identities drive development of new technologies and the cycle continues.

Toby Shorin sort of touched on a similar idea in Life After Lifestyle, where consumption and platforms drive identity. And when Boomers are like “How do I relate to Gen Z?” this is the core problem - different generations operate in different economic realities and form identity through fundamentally different processes. Technology is accelerating differentiation. Economic paths are becoming more extreme. Identity formation is becoming more fluid.

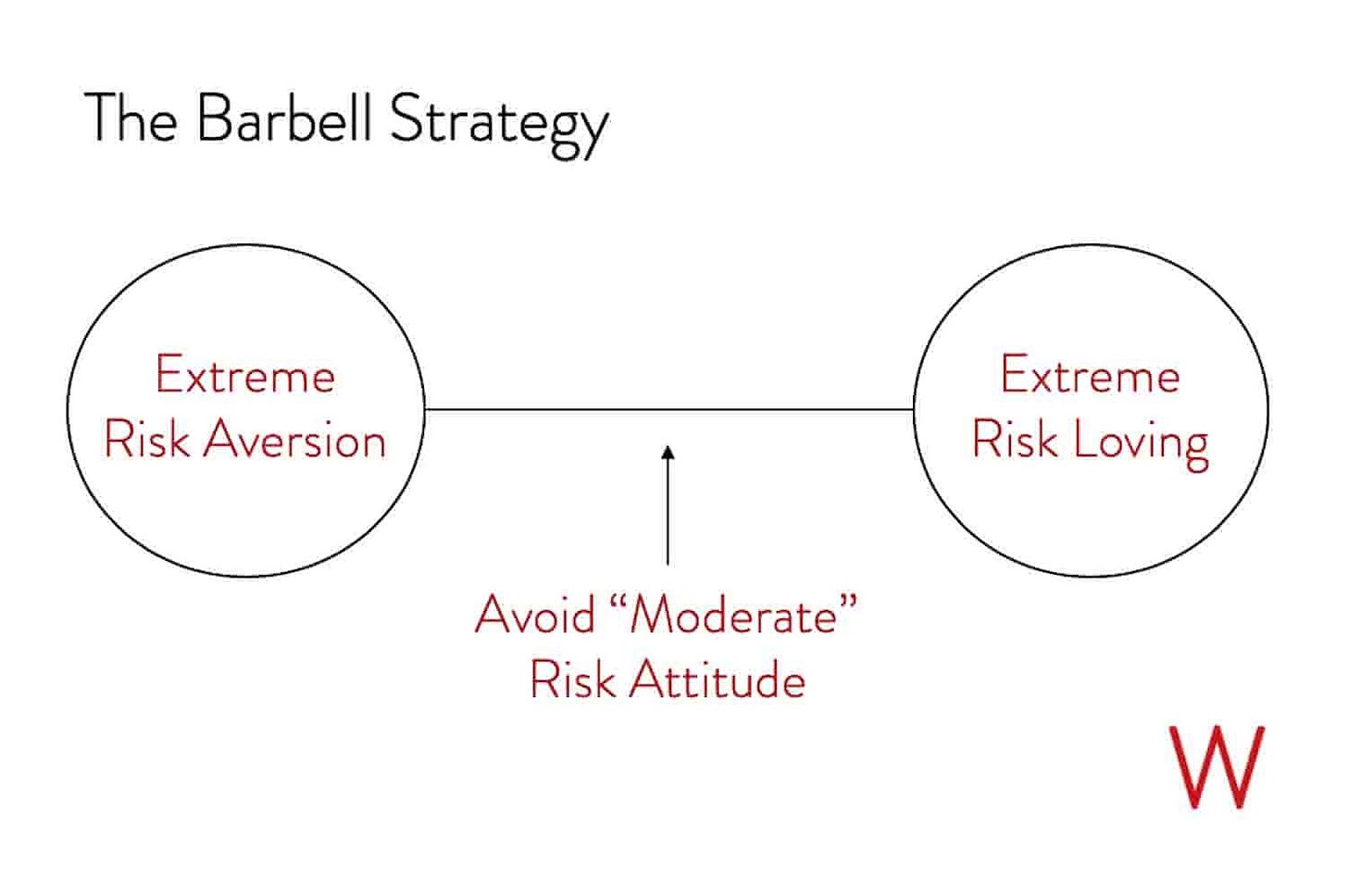

The Barbell Strategy

Responses to this digital reality and fast moving world create a version (somewhat) of Taleb’s Barbell Strategy - we increasingly have a world split between students (1) forgoing college to pursue the trades and (2) those gambling everything on digital moonshots. Taleb writes that the barbell strategy is a “method that consists of taking both a defensive attitude and an excessively aggressive one at the same time” - here, we see people doing maybe one or the other.

The barbell economy creates its own culture:

There are "safety seekers" who might choose to skip the college debt trap, take steady jobs, and find identity in stability amid chaos. The toolbelt generation.

Then the "digital gamblers" who might embrace the creator economy all-in, crypto speculation, and AI startup moonshots. These people find identity in potential rather stability. 17% of all crypto buyers are Gen Z (76% are Millennials).

And to be clear, the middle path still exists and is evolving. I am being intentionally unnuanced for the sake of making a point. Many people are still going down the traditional road (and rightly so!), albeit with more skepticism. There are many sectors combining traditional careers with technology.

Bridge builders are likely the future, with AI-enhanced roles, people blending traditional careers with digital work, and the continued proliferation of the gig economy (like… Uber with guns). Universities are offering more credentials, online expansions, and AI upskilling programs to try and keep up.

Vice President JD Vance wants AI to be a “complement, not replacement” to the workforce, so hopefully that’s the policies that this administration creates. AI will make new jobs as well as destroy old jobs. There will be both automation - 375 million people might need to be reskilled by 2030, according to McKinsey - and augmentation. There are more questions than answers with all of it, so with everything, there are caveats.

But during times of uncertainty, people tend to retreat to the edges. With AI, we're watching both an economic transformation and the birth of entirely new ways of understanding who we are and how we fit into the world. For better or worse, the rise of figures like Andrew Tate alongside the growth of democratic socialist movements among young people are competing narratives about how to make sense of a world where traditional economic stories no longer work. I mean Argentina (the country) launched a $4b memecoin that thousands of people lost millions of dollars on and the President is now trying to back out of responsibility for.

Of course nothing makes sense anymore.

STEM fields, long considered "safe" careers, are being transformed overnight through either getting their funding gutted or from rolling layoffs in tech. And to be fair, this sort of happens every few decades right? The Internet, the Industrial Revolution, the Agricultural Revolution - the AI Revolution is another fundamental rewiring of how value is created (and captured) in society.

Both ends of the barbell are actually rational responses to technological transformation. The safety seekers aren't afraid of risk, but rather they're making a calculated bet. The digital gamblers avoiding stability, but rather they're responding to an economy that increasingly rewards exponential outcomes.

How This Affects Their Politics

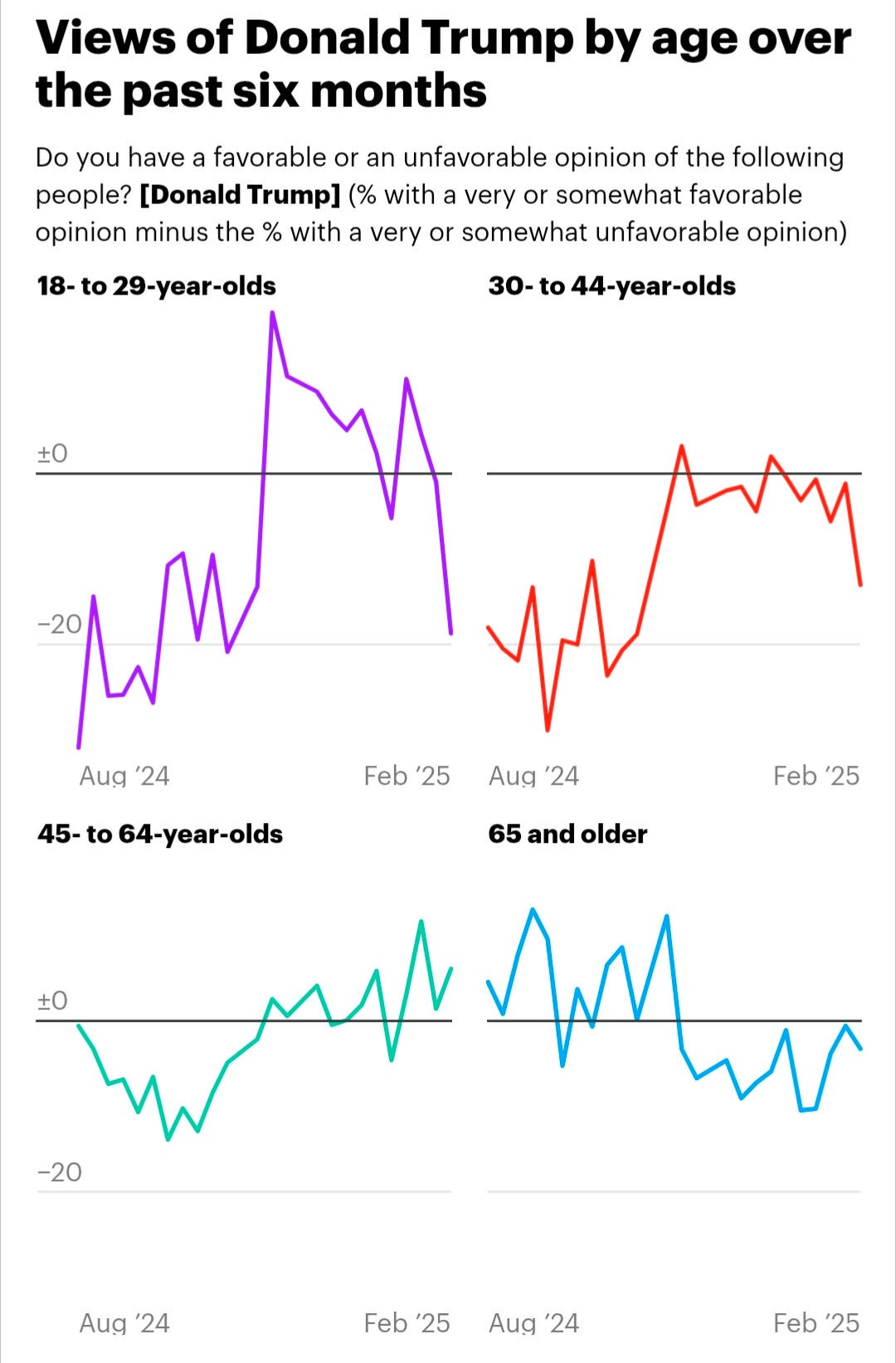

When things are uncertain, people retreat to the edges - but they also vote for ‘new normals’. You can see the Gen Z break in the electoral data (Derek Thompson most recently wrote about this, as well as John Burn-Murdoch and Alice at the Great Gender Divergence and go into far more detail on the ideological positioning than I will here.)

There was a 23-point drop in Democratic margin among 18-24 year olds while 25-29 saw only a 3-point decline.

According to VoteCast, most young Trump voters “were more motivated by the economy than by immigration, were broadly concerned about climate change, and wanted more government involvement in health care and canceling student loan debt” and “about half of these voters said the economy and jobs are the top issue facing the country, compared with about 4 in 10 older Trump voters.”

They are less likely to identify as “conservative” and mostly voted for him because they wanted a better economy. To keep banging on the drum - the back half of this generation is graduating into a land of uncertainty.

Many younger Gen Zers came of age watching political gridlock, rising inequality, and a system that seemed increasingly detached from their lived reality. They saw institutions that refused to adapt (and as of recently, have shown a lack of resilience). They were locked inside during their formative years.

They also get their information from social media (as do most age groups at this point) and that has further fragmented political engagement, creating echo chambers that reinforce more extreme perspectives. For young men, there has been a world where you’re always painted as the bad guy, something that is exhausting and something I talked about more here with my little brother2.

The key takeaway is that Gen Z is shifting politically - and their engagement with politics is being shaped by a digital-first reality. And now we are seeing what is happening when people decide they don’t like that reality, as shown below. Immediate gratification makes it harder to understand long-term consequences.3 The world of algorithms and AI can be designed to suit one’s every desires, but when reality comes into focus, we can’t scroll away from it.

I wrote a very long piece about why Trump won that focused on uncertainty, structural affordability, and fear - and that’s what the younger Gen Z’s are facing. Add AI into this mix, and the rocky path gets rockier. Traditional professional paths that once promised stability and maybe the ability to buy a house one day might not even exist in two years. Couple this with increased zero sum thinking, a lack of trust in institutions and subsequent institutional dismantling, and the whole attention economy thing, and you’ve got a group of young people who are going to be trying to find their footing in a whole new world. Of course you vote for the person promising to dismantle it and save you.

How This Compares to Previous Generations

The Boomer generation, born 1946 - 1964 (please remember these are broad sweeping generalizations) had a somewhat clearish wealth-building formula (generalization generalization generalization):

Career progression + home appreciation + retirement savings, supported by mostly predictable returns on education.

This economic reality shaped their worldview, their sense of self, and their understanding of success. They are the wealthiest generation to have ever lived, thanks to “affordable housing and strong equity markets” according to Allianz.

It of course was (1) still hard (2) clearly doesn’t work for everyone, as 43% of Boomers have no retirement savings (perhaps an indictment of the move to 401k from pensions) and (3) is a broad sweeping generalization.

But the general formula that worked for a lot of people then was work hard, buy a house, save for retirement, trust in institutions. There was incredible shakeups, like the stagflation of the 1970s and the mega-high interest rates of the 1980s. But over time (and perhaps the same will happen for younger generations, it usually does) things smoothed out to an element of predictability.

The Wealth Generation Shift

But some of the Boomers that have benefited from this system have also participated in its dismantling. Not out of malice, but through thousands of small decisions that prioritized short-term gains over systemic stability. One example is the persistent public outcry at any attempt to build homes (as well as zoning, etc, I’ve talked about it a lot), so housing has become an investment vehicle rather than shelter.

For many reasons, baby boomers still own most of the nation’s 3-to-4 bedroom homes - they own 38% of homes nationwide despite comprising just over 20% of the population. Millennials haven’t caught up to Baby Boomer life marker homeownership rates and homeownership rates are even lower for Gen Z than Millennials at the same ages, according to a study out of Berkeley. In 2025, the average Gen Z worker needs 14 years to save a home down payment, twice as long as Boomers. This isn’t frugality failure, it’s a system where 72.9% of wealth sits with those over 55.

There’s also systemic issues, like education costs and healthcare costs skyrocketing. Boomer wealth was largely built through time and institutional trust. It’s a bit different now. Time is expensive now. Trust has eroded. Some are saying that democracy is fake! Millennials and Gen Z own 71% less wealth than their representation in the US might predict, according to the St. Louis Federal Reserve.

This is a form of the paradox of abundance where we have more opportunities for extreme wealth creation than ever before, but the reliable paths to modest prosperity feel like they are disappearing.

And there are opportunities - a creator with the right viral moment can generate more wealth in a week than their parents saw in a year. A lucky crypto trade can outperform a decade (or two) of traditional saving. The paths to wealth have been reimagined, to say the least and it feels like the in-between is disappearing. While Gen Z navigates all of this, the institutions meant to stabilize these systems are themselves crumbling.

Our Fiscal Reality

Understanding one’s place in the world also gets into our current fiscal reality. I am going to zoom in here to explain what’s happened over the past few weeks, and then I’ll apply the generational lens.

Government Debt

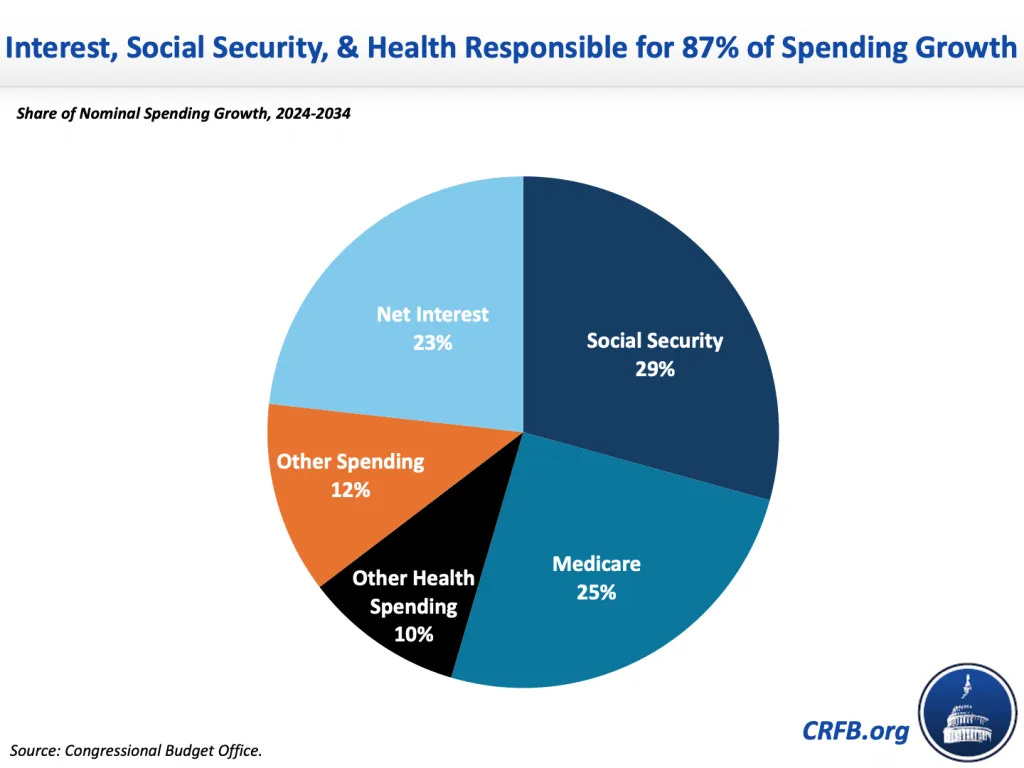

DOGE’s job is to find waste and fraud in government spending (I wrote more about DOGE here if you need a primer) but the problem with government spending is that it is mostly (1) social spending like medicare and medicaid, which really can’t be touched and (2) interest payments. There are plans to cut Medicaid and Social Security benefits could be disrupted due to DOGE, which could be quite harmful to the people who rely on them.

Interest has become an increasing part of spend (and ideally, we would focus on getting inflation down so the Fed can cut instead of enacting inflationary tariffs, but alas) and that’s unwieldy to manage too.4 None of these can be solved by taking an axe to the government, unless there is comfort with people dying.

DOGE

And to be clear, we do have a massive debt problem. But DOGE is having trouble finding actual fraud and keeps on making silly mistakes. The Social Security fraud that DOGE uncovered is just a data problem (which should be fixed, but again, money) and the real problem with SSN is that people actually use fake SSNs to work and pay taxes - not to steal money, but to pay into the system. Also, we are not sending out billions of dollars to people aged 150. We have the data.

Our main headwind is that we have an aging population and a demographic crisis. As Kevin Bryan said the government “isn’t filled with fraud – it is almost all old age transfers and military and interest.” Also, saving money doesn’t always equate to efficiency.

VATs

There are other examples of policies that are confusing, like Donald Trump treating VATs (Value Added Taxes) as tariffs and then putting reciprocal tariffs on countries that have a VAT. I’ve written at length about tariffs and produced an Indicator for Planet Money episode about them. VATs5 do not impact American exporters. This is like getting upset that French people have to pay taxes on their stuff domestically6. It doesn’t impact us.

Erica York, who is doing incredible work at the Tax Foundation, wrote about it here. The VAT applies to all products sold in France, whether imported or domestic. The tariff only applies to imported products.

Firings

There has also been mass firings of FAA workers (who are going to be replaced by contract workers it seems, mere days after the deadliest commercial plane crash since 2009). There was a firing and then rehiring of nuclear safety workers. There was a firing of people who operate the Veterans Crisis Line, people who take care of those who fought for our country. There was a firing of park rangers, who protects the beautiful spaces America has been afforded. There are many more examples.

275,000 people have lost their jobs, which is 10% of the federal workforce (and half of the job losses of Feb 2009). One-third of all federal jobs are held by retired military. The ‘deep state’ seems to be civil servants who work at NIH and CFPB, who try to keep America somewhat safe from predatory financing and disease. Again, no one was saying that there wasn’t waste, but at what cost?

The cost of rebuilding after so carelessly firing, rehiring, dismantling, could be enormous. Firing 25% of federal workers would reduce government spending by only 1%. Also, ~80% of the Federal workforce works outside DC. There are all sorts of lawsuits trying to slow all of this down, but the erosion of trust has already taken place. Finally, it’s a bit difficult to square the concern over the national debt with the promise of more than $5 trillion in tax cuts. On a different note, Andrew Ferguson, the new head of the FTC, actually plans to keep Lina Khan’s guidelines into effect.

Geopolitics

Then there are examples of isolationist policies, where the US is threatening other countries in a very real way. America has become adversarial to our allies, especially Europe. The culture wars have gone global, and that puts other countries at risk if they stay entangled with the US. This is based on the rhetoric of JD Vance at the Munich Security Conference7, where he made it very clear how he hopes the US will position (and deposition) itself.

I wrote at length last week about the geopolitical repositioning of the US (the move from a unipolar to a multipolar world) and Trump has offered Russia several concessions while blaming Ukraine for starting the war (which is not true). It’s another sign of the US stepping down from its role as leader of the free world.

If we evaluate how others think of this just from a market perspective, European stocks have beaten the S&P 500 by almost 10% since Christmas. The two-year breakeven rate, what traders expect inflation to average over the next two years, is more than 3% (a bet that inflation will accelerate).

Money tends to talk louder than words do.

The Future

Charles Mann wrote an excellent piece about the luxury that the US has in ‘not knowing’ - we truly don’t really know how anything works (which is a problem and that births conspiracy theories). He writes “they wanted a better world, but they didn’t know how this one worked.”

As any mechanic will tell you, you can’t fix a system unless you know how it functions. And that’s what the problem seems to be right now. We are seeing a systematic devaluation of institutional knowledge in favor of some form of misguided intuition with some quite far reaching executive power. I tweeted about this phenomenon and a lot of people responded with:

Well, we are broke and we needed to do this

The bureaucrats need to be replaced and also were bad at their jobs and there are too many of them (the federal workforce has actually remained steady as a % of the overall workforce)

Bill Clinton did mass firings8 - (he did, but he did it legally and with careful review, whereas the current approach is potentially unconstitutional (Mike Pence, former VP, has a good read on that here) and apparently not what Trump’s voters actually wanted)

Twitter did do mass layoffs when Elon took over, and the app was totally fine - it was buggy for a bit (and still is) but it’s an app that 27% of the population uses. It’s not the US government. Taking an axe to essential services probably isn’t the best way to go after waste and efficiency9. Subsequently privatizing those services will also be costly.

Domestically, there are two shocks created, as Diane Swonk wrote - (1) massive uncertainty causing people to delay decisions and spending and (2) fear that prices will continue to rise, leading to hoarding. This palpable loss of direction has severe consequences for the economy, including potential stagflation. That’s why gold is on the move - uncertainty.10

Internationally, it’s a scattering of chess pieces. Singapore’s defense minister stated that the US has evolved from “a liberator to great disruptor to a landlord seeking rent”. they're describing a shift in how power views its responsibility. And right now, the US doesn’t see that it has any responsibility at all. As Ben Hunt said, “it’s the pursuit of power for power’s sake.”

Guess who is about to inherit this new world?

The Normal Trap

My former professor Dr. Chhachhi said "the opposite of rationality isn't irrationality - it's being normal”. He captured something really important. He didn’t mean this exactly, but I am extrapolating - the "safe path" (corporate job, 401k) might be the riskiest bet.

When AI can eliminate entire professional categories overnight, when traditional credentials lose value faster than you can earn them, when digital platforms can create overnight millionaires... the question is about how we define stability in an unstable world.

While Gen Z has adapted by finding alternative paths to success - from trades to creator economies - institutions are struggling to keep pace. Universities experiment with modular education, corporations are rethinking credential requirements, and policymakers push for reforms, but these changes are often too slow and too limited. The challenge isn't only modernization - it’s legitimacy, right? When people say the government is "broke," they're not just talking about finances, they're talking about trust.

This is the core tension of our moment: Gen Z's 'algorithmized self' isn't a choice—it's an adaptation to systems where viral moments outweigh career loyalty and where institutional stability has been replaced by algorithmic opportunity. The paths to wealth and meaning have been fundamentally restructured by technology. The reality we face is stark: crumbling institutions, a demographic crisis, and a federal workforce being dismantled (regardless of your views on if it’s good or bad, that’s what is happening).

When I talk to people across the country, their concerns are greater than traditional political divisions. They're wrestling with questions of identity, meaning, and community in a world where traditional narratives about success and stability no longer hold.

What looks like a conservative shift among young voters might actually be something more fundamental: a generation's attempt to navigate a world where institutions promise stability they can't deliver, where algorithms offer opportunity without security, and where the very nature of work and worth is being redefined. It’s constantly evolving, and it’s not just politics - it’s the very nature of self being called into question.

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice or recommendation for any investment. The Content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.

This piece is pretty deterministic in terms of the impact technology has, and there are of course other things to consider like policy choices, economic structures, and opportunity access. However, I do think the role that technology is played in how young people see the economy deserves to be analyzed.

Young women have shifted leftward partially because a lot of the positioning of conservatives is a backpedaling of rights that were afforded to women only recently.

An agency called the Government Accountability Office already does DOGE’s job - they found found $70 Billion in savings last year and $2 Trillion in waste since 2003

If the US exported a $20k car to France and we had a 10% tariff on the France, that would be a $2k tax. So the base price of that car in France would be $22k, so the seller could recoup the tax. But the VAT is only applied domestically in France - let’s say another 10%, which would be $2.2k - and the final consumer price would be $24.2k - the VAT doesn’t impact the US at all.

The IMF has estimated that Europe’s internal barriers are equivalent to a tariff of 45% for manufacturing and 110% for civil services, so the EU actually really does need to figure some stuff out

There is also an interesting take where the US can’t really preach at other countries at this point, because we don’t “have the power to enforce the sermon” right now

Lots of people are comparing the job cuts now to Clinton, and it's quite different. Clinton's job cuts followed a careful 6-month National Performance Review that identified where reductions wouldn't harm services. The cuts were implemented gradually with bipartisan support (and were signed into law after a review period) allowing agencies to adapt to new normals while maintaining functionality. This was a careful approach! The government must maintain essential services for all citizens (as Steve Bannon has talked about) which is why the *method* of reducing the workforce, not just the end goal, matters. Again, no disagreement in waste, but moving too fast ultimately creates more waste in clean up)

For example, if we collected all the taxes that the US was owed, we’d cut the deficit by $711B. Firing all civilian employees would cut the deficit by $271B.

Alex Good has a video that dives into all the directions this could go if things get really extreme - he himself warns the views are fringe, but it’s an interesting listen.

Great post. My two daughters are Gen z, like you. 23 and 25. I'm acutely sensitive to the lack of security they feel at the speed with which the world is changing. I was reading a post by someone I follow who had this to say (among much more): "... the speed of (jobs) replacement will make ... the experience of the steel, shipbuilding, tooling, electronic components, durable goods, automotive and any other industries you can think of look like a stroll in the park"

Who wouldn't be unnerved coming of age during a time like this? I know that pretty much everything I do now for income will be done by AI within 10 years. I'm 64 and it unnerves me. I try to imagine what it is like for your generation and it makes me rethink every stupid knee jerk reaction my generation has for the younger generation.

As a Gen z'er, Kyla once again captures how I feel but lays in out in a much more understanding way than I could articulate.

I currently work a pretty unfulfilling corporate job, making good money for my age (25) but one thing that I struggle with being 3 years out of college is finding that meaning in a job. Seeing people that have worked the company for 10-15 years, really hits me hard. The concept of staying at a company for that long is difficult for me the think about. I mainly struggle grasping that timeframe because of what it is like to be Gen z in America. Everything Kyla said in this piece rings true. I am afraid of AI taking my job, I see older people who are far more worried about short-term outcomes rather than long term effect. For example, my parents (who are very liberal) live in Nashville, TN, our neighborhood is zoned for single family housing on one acre land. There's plenty of room for more housing, more duplexes. But there is stiff resistance to changing the zoning laws because everyone is afraid that it will hurt their precious value of their home... And what really ticks me off is that most of the homes in this neighborhood were bought 20+ years ago and have most likely already been paid off. My parents do not see the long term benefit of creating more housing for my generation, they want the short term benefit of having their home remain high value, just so they can sell it in the next 10 years.

Being a Gen Z'er is so weird and stressful the more I think about it, but posts like this and others is really making me rethink how I live and what I want my life to be. As I approach turning 26, I am really considering going to flight school and work my way to becoming an airline pilot. I crave meaning in my jobs, and I want to take a risk on myself (which I feel like I haven't done before).

Loved the piece, Kyla