Looking ahead!

As a quick update on me: 2023 was very kind. I was able to speak at so many universities and conferences (thank you thank you thank you), work on some dream projects, finish my book !!! (which I am so excited to share with you), write for Fast Company, and so much more. I am so thankful, especially to you, for your support. Wishing you health and happiness in 2024!

Three quotes -

“The aim of art, the aim of a life can only be to increase the sum of freedom and responsibility to be found in every man and in the world… there is not a single true work of art that has not in the end added to the inner freedom of each person who has known and loved it.” - Albert Camus

“Love has never been a popular movement. And no one's ever wanted, really, to be free. The world is held together, really it is held together, by the love and the passion of a very few people. Otherwise, of course you can despair. Walk down the street of any city, any afternoon, and look around you. What you've got to remember is what you're looking at is also you.” - James Baldwin

“People prefer bad news to good news because bad news provides them with a ‘survival emotion’ while good news threatens them with change” - Marshall McLuhan

Ok, but the economy?

Silicon Valley bank imploded. Taylor Swift started her Eras tour. We entered the debt ceiling debate yet again. OpenAI blah blah. Labor market housing market stock market crypto again somehow inflation federal reserve sentiment gas prices fear.

This year has been tiring for many people, for a lot of reasons

Good things: We managed to skirt a recession (again!) and get inflation down (somehow!) and maintain a relatively strong labor market (excellent!), and still grow the economy. There were historic labor movements, like the UAW strike, that allowed employees to demand more from their employers.

So many economists were wrong. Everyone thought that we would be in a recession this year. In 2022, Bloomberg had this post stating that there would be a Forecast for US Recession Within Year Hits 100% in Blow to Biden and that sentiment carried into 2023.

Wrong! 85% of economists thought that we would be in a recession by end of 2023.

Big wrong! And we weren’t! Everyone learned a lot of valuable lessons on how the economy works in the post-pandemic world. As Adam Ozimek writes in The Simple Mistake That Almost Triggered a Recession why they were wrong, with ‘their pessimistic views about the labor market’ being a main issue.

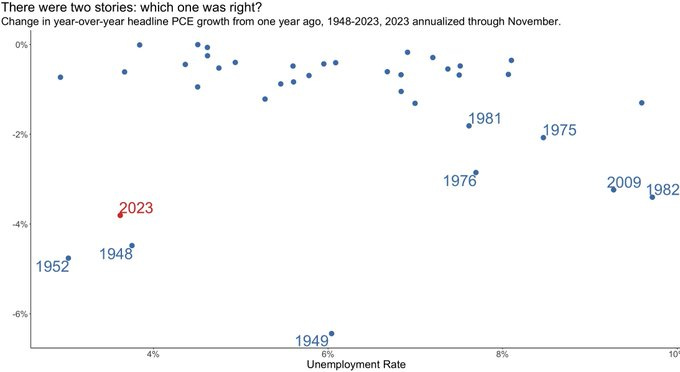

We learned that we don’t have to destroy the economy in order to save it.

But this same thing sort of oopsie-daisy-analysis happened in 2022 when The Street published their 2023 outlooks, and then all of a sudden, China did a complete u-turn on Covid, the weather got warmer in Europe, saving them from an energy crisis, and the BoJ actually took some monetary policy action. No one really knows, ever.

The reason that I am highlighting that is because the world is uncertain and I think that is the word for 2023, uncertainty.

And, of course, the idea that the economy is GOOD in an uncertain world, despite all of it can feel very frustrating. It’s two things

The economy can be fine

We can continue to live in this crushing uncertainty where it feels like things could be really bad at any moment.

A fine economy doesn’t equate to a perfect world, and it certainly doesn’t mean that any other problems were absent. We are still dealing with the pressure cooker of price increases, a housing crisis, and compounded uncertainty from the past few years of immense societal pain.

Quickly, the Vibes

But the ‘vibecession’ idea was really important for this year to delineate the disconnect between consumer sentiment and economic data.

The most important part about the ‘vibes’ becoming a part of the discourse is that we are acknowledging that how people feel actually really matters for how the economy performs.

Vibes, for better or worse, are self-fulfilling. Of course, we already know this - the Fed closely watches inflation expectations, and both Soros and Keynes came up with reflexivity and animal spirits, respectively, to describe the role that human behavior has in shaping reality.

But we always perceive things to be worse than they are, especially in the historical rearview mirror. One of my favorite articles from this year, the Illusion of Moral Decline by Adam Mastroianni, was about how wrong we are about most things pretty much all of the time - especially the past!

It’s very easy to feel like you know something about the past without actually knowing anything about the past. I just showed you data from more than 500,000 people who were asked whether morality has declined, and virtually none of them said “Gosh, I don’t know.” But for them, that was the right answer. They don't know… The past is a foreign country, but we all have the vivid delusion that we’ve lived there for a long time and know everything about it.

So we have this general perception that everything is always getting worse, despite the fact that it isn’t? And we have these rosy glasses on for the past, which makes everything even more confusing.

The Federal Reserve

We achieved a soft landing.

The indicators that the NBER committee looks at to determine if we were in a recession were not pointing toward recession and unemployment is stable and inflation seemed to be getting closer to becoming manageable and real income is fine and there was job growth.

But all throughout this year, the Fed was still staring at the ceiling and watching the fan spin around and wondering if they made the right choice. The Fed has a dual mandate right? Price stability and maximum employment. But they are also managing the eyes and ears of investors. They have to be the vibe setters, and that was so incredibly apparent this year. Earlier this year, Neil Kashkari of the Minneapolis Fed compared the Fed versus Wall Street to a game of who will blink first -

I’ve spent enough time around Wall Street to know that they are culturally, institutionally, optimistic… They are going to lose the game of chicken.

The tough part for the Fed is that they can’t control the things that people are most mad about - food prices and gas prices can’t be attacked with the rate sledgehammer. So they have to be like “smile and wave boys” while managing a massive economy without actually managing it. As Jon Sindreu wrote in the WSJ -

Uncertainty makes it more attractive to follow the herd, because getting it wrong is less costly if others are also wrong. Rate-setters, particularly at the ECB and the BOE, have struggled to offer theoretical justifications for their actions lately, often warning about wage-price spirals without their own research bearing it out. They are in a tough spot: Their reputations depend on hitting an arbitrary 2% inflation target when factors out of their control often dominate.

So the Federal Reserve raised rates from February to May, bringing the Fed Funds rate up to 5%. They paused in June, and then hiked in July, and then paused from September - December, keeping rates at 5.5%. This was a lot! Everyone was worried!

The Fed was paying very close attention to this metric called “core services ex shelter inflation” which is a measure of everything we need to survive (haircuts, transportation, etc etc).

The metric is linked to nominal wage growth, so the Fed was like, “WE MUST SQUASH THE LABOR MARKET” because it seemed like that is where the inflation is coming from.

Luckily, their rate hikes didn’t destroy the market, and that narrative has shifted, but it was spooky and worrying.

Now, the Fed is looking at rate cuts. They have sort of beaten inflation, right? And now its time to normalize the economy, with the very delicate balance of why to cut rates, when to cut rates, and how to cut rates without the stock market losing its mind.

Fiscal Policy

The backdrop of general politics made the Fed’s job even harder.

Dumb: We were dealing with the incredibly idiotic thing that is the debt ceiling, which blew a ton of money and time (enough money that it was more than they appropriated to the National Park Service over the past five years).

But the dumb worked: Big fiscal actually saved the economy. Big fiscal saved the labor market. The United States was able to have stronger growth than any major high-income country while having lower inflation rates than Japan! Which is phenomenal!

The frying pan charts developed by Alex Williams over at EmployAmerica show how successful fiscal policy was in not only helping the economy recover but pushing it past the 2019 trendline.

But fiscal is disorganized. Bidenomics, for however you feel about Biden, was successful. But it focused too much on manufacturing (something that is important but doesn’t really impact the everyday American), so people felt left out. As Kate Aronoff wrote in The Case for Pool Party Progressivism -

Why not give people something to enjoy about decarbonization instead of just a daunting to-do list of large-scale infrastructure projects? Call it Pool Party Progressivism: a politics recognizing that the unionized workers erecting all those wind turbines and solar panels might want to go sit by the water with their friends and family after work, grow zucchini next to their neighbors, or join a rec soccer league.

Especially when student loans started back up, the housing crisis got worse, the American Rescue Plan ended… it was like, “well shoot dude what’s in it for us?” People saw how successful policy action could be during the pandemic and then when the government was like “heh nevermind” I think that hurt a lot of people. And I don’t think every social program should be kept in place, but a general social safety net wouldn’t be a bad idea.

The Ladder is Wonky

Part of the issue is that there isn’t a beginner mode anymore. The last car in the US market that sells for under $20k, the Mitsubishi Mirage, is being discontinued. There aren’t starter homes. There really aren’t starter jobs. And demographics are weird.

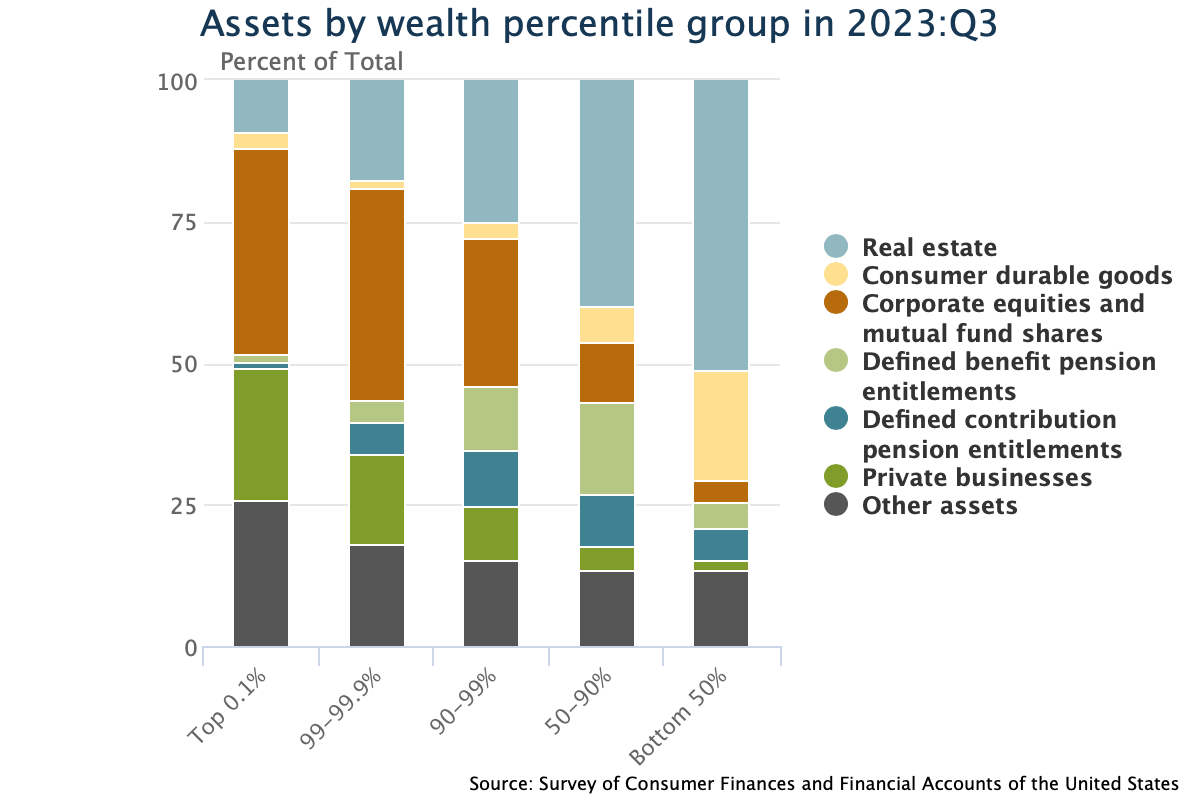

Boomers are very wealthy (which checks considering they’ve spent more time here on Earth) but there are concerns. Americans age 70 and older now hold nearly 26% of household wealth, the highest since records began in 1989 (and roughly $77T in wealth). Spending by older households is up 34.5% from 1982, compared with 16.5% for younger households.

But now the worry is that people aren’t having kids. None of the world's 15 largest economies now have fertility rates over 2.1. The Economist wrote -

The falling number of educated young workers entering the labour market will also reduce innovation, sapping economic growth across the board. Over time, this effect may prove the most economically damaging result of the greying of the rich world, eclipsing growing bills for pensions and health care.

But we all know why this is happening. Unfortunately, kids are expensive and we have a childcare crisis. The Zoomer Question, and in it the author addresses this sort of demographic stagnation that we are facing, writing

Our immense reservoirs of money and instrumental cleverness no longer look so impressive when compared to our inability to change the fundamentals of life. A country which neglects the development of its people, institutions, and environment will have no success in transforming itself, especially if it aims to recapture the industrial capacity that depended, ultimately, on social facts that no longer exist. We are thrown back, embarrassed on the most basic questions: not even an empire’s worth of effort can compensate for our intolerance of treehouses for children. We must learn to speak of true education, of health, food, cities, and sculpted land. We must speak intelligibly, or not at all.

So we have a good economy, but we have these flashing caution signs lining the economic highway.

The Labor Market

The labor market was weird! There was the incentive for the Fed to destroy it (to get inflation down). The media then came up with all these horrible terms to describe it, like quiet quitting and the great resignation (get a grip!) and all those words just meant that we had a tight labor market. And a tight labor market could be inflationary, so blah blah, everyone was freaking out.

The labor market was really bifurcated too.

Techcession: There was a ‘techcession’ that contributed to a lot of the overall bad vibes. The big tech companies were like “whoa ok the Fed raised rates and now money is expensive… no more bean bag chairs and endless burrito bars.”

Tech suffered for a lot of reasons - the pandemic was a tech bubble, growth firms are rate sensitive (so the Fed hikes), we were/are in an advertising recession, and then there was an element of social contagion - if one firm is firing, the rest are more likely too. Of course, big tech began to hire again, but we had exited this golden era that a lot of people were really reliant on.

There are other parts of the labor market that suffered too.

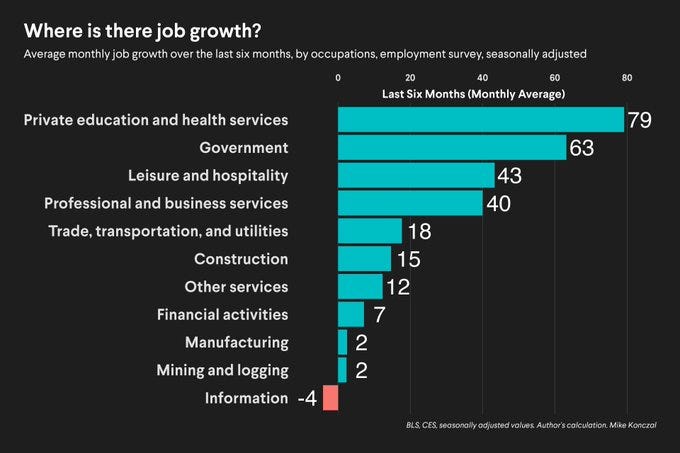

But other industries thrived! Healthcare, manufacturing, etc, all experienced growth. In fact, we saw huge labor market gains in two ways - strikes and wage growth.

Labor movements: UAW, the writers strike - employees were finally able to demand more from their employers.

Wage growth: For the first time in forever, lower income workers actually experienced increasing wages

But there are a lot of things we have to do to fix the labor market.

Improve immigration: Economists predict that doubling the H-1B visa cap from 65,000 to 130,000 would increase the GDP per capita growth rate in the US by almost 10%. There are also massive opportunities to improve parental leave options and improve options for people with disabilities.

Improve training. A lot of people want to become electricians but no one wants to train them. To Ditch Fossil Fuels talked about the issues in trade, and “the number one reason for all the openings: “Available candidates are not qualified to work in the industry” which is an industry problem to solve.

People WANT to work. That’s one thing we learned. The share of prime working age Americans with a job was 80.8% in April, the highest since 2001 and well above the 25-year average. The percentage of 25-54 year olds employed (prime age employment rate) is the highest it has ever been since 2001.

Now, how AI will impact all of this is unknown. We have seen the fragmentation of blue-collar work in the past, and we are likely seeing the fragmentation of white-collar work now. And AI could exacerbate all of that, or it could be complementary. Only time will tell.

The Stock Market

This was a year that bonds were finally hot! Treasury bill yields were finally above the yield that most people got on their savings accounts, which was a double-edged sword.

Higher yields makes US government debt more expensive to finance, which isn’t great, because there is a lot of US government debt. The debt ceiling debacle made all of this worse, with Fitch downgrading the US because they just don’t have their stuff together

With interest rates rising and divided government, it was an ideal time to reduce deficits but of course, yeah, that didn’t happen.

Rates also hit more than just government debt, it hits all types of debt. The surge in interest rates is slamming the $10 trillion market for corporate debt even worse than last year. An illustrative portfolio of investment-grade bonds (sold by Coco-Cola, Microsoft, etc.) is now worth $612,000 versus $1 million in early 2022.

In terms of the stock market, Nvidia was king because they are the key to AI. Beyond that, according to Hendrik Bessembinder’s research -

Nearly 60 percent of companies that have been public in the U.S. over the last century or so have failed to create value, defined as earning total shareholder returns in excess of one-month Treasury bills. And only 2 percent of companies were responsible for more than 90 percent of the aggregate net wealth creation.

Welp.

The Housing Market

Homes are expensive. And there are not enough of them. Home price gains drove ⅓ of the increase in inflation, there was a massive mortgage rate shock (because of the Fed raising rates), and then there has been a huge run-up in home prices. There is a sheer lack of affordability that rivals that of the housing bubble

Traditionally, a house in the U.S. costs about 3-3.5x the median family income. Now it costs 4.5x.

Housing affordability deteriorated massively over the past 3 years.

And there is a whole conversation to have about this. Like why do we need to treat aging homes into investment vehicles by artificially constraining supply? And that gets into my favorite chart of all time -

Housing is wealth for so many people. And we need to figure out how to redefine what wealth means, or else the housing crisis will never really go away. But it's frustrating, and it's creating a bifurcation because there are a few groups of people - (1) those with a ZIRP mortgage and those without and (2) those who will inherit boomer real estate and those who won't.

Building more homes is the obvious solution, but the path to do that is difficult. There are zoning issues, labor issues, supply costs, etc - it’s a mess!

Commercial real estate is a mess too, as US office buildings are only about 50% as full as before Covid: Kastle Systems. Columbia & NYU professors estimate that the value of office property across US cities is 38% lower than pre-pandemic, equaling a loss of about $500 billion.

Going back to the point about AI, we live in the real world right? AI could probably help with the housing crisis, but instead, we are using it to make digital girlfriends because that is where the money is.

Inflation

And, of course, inflation. Kashkari said that he gauged inflation by the price of Stouffer’s lasagna, and I think that’s very emblematic of the broader economy.

Everyone hates inflation. It was this massive pressure cooker that just boiled over too, because we’ve been dealing with price increases for like three years. That’s the primary cause of the vibecession and whatnot, things are expensive. According to Navigator

The aspect of the economy voters are most upset about is food prices. Not shocking, given that grocery costs rose 20% from Jan. 2021 through Jan. 2022, compared to about 12% for core CPI. They've flattened out since, but sticker shock is still there.

And of course, you can get more granular with inflation.

U.S. fiscal stimulus contributed to excess inflation of about 2.6 percentage points domestically. Used car prices were a huger drive of CPI.

Energy prices were important, but a paper came out stating that rising energy prices were not the main determinant of the surge in US CPI.

Services inflation was driven by shelter mostly.

Covid caused a "demand reallocation shock.. and is able to explain a large portion—3.5 percentage points—of the increase in U.S. inflation post-pandemic."

And of course, there was a massive conversation about price gouging. The Sellers Inflation paper written by Dr Isabella Weber and Evan Wasner caused uproar and got conflated with the concept of greedflation. Dr Weber was pointing out that firms can (and will) hike prices in an emergency, but it isn’t always due to greed.

But of course, greed is subjective

Everyone got pretty good at pricing strategies due to technology and other shocks that provided a safe way for them to raise prices. Is that greed?

And then everyone was like, “inflation is caused by the wage price spiral” but this actually points back to corporations too. Based on BIS data

“Corporate pricing power in advanced economies is at historic highs; mark-ups have increased significantly, while trade unions are much less powerful than in the 1970s and 1980s, reflected in a decline in trade union density.

Companies were raising prices! It wasn’t workers demanding more money!

Nestlé pushed up prices by an average of almost 10% in the first 3 months of the year, close to the fastest pace in more than three decades. Kimberly-Clark also raised its prices by 10%. Profit margins are starting to expand again as a result.

PepsiCo raised its revenue-growth forecast and saw strong demand despite raising prices 13% in the latest quarter.

Finally, it wasn’t really money growth. 1% money growth leads to only on average about 0.3% higher inflation! In other words, it’s not 1 for 1. As Steve Hou wrote, “much for ‘inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.’” As Mike Konczal has highlighted, we have 1948 inflation, not 1970s. We are living in supply-side constraints with surge in demand, not the 1980s energy crisis.

And now inflation is lower than when Biden took office, which is great. But that doesn’t matter because people want deflation. As Nick Timiraos wrote

Why consumers will remain frustrated about inflation even if it continues improving: Americans usually focus on the price level, or the absolute price of the things they need and want. This won’t go down even if the rate of change (inflation) moderates

A General Scope

Ok so the economy - now, the people.

I have been thinking a lot about the development of ‘algorithmic selves’. How people define themselves is encompassed by many real-world things, but it’s also becoming defined by algorithms. Everything from Spotify to dating apps to Instagram shapes a part of our personality.

And what happens when we can’t separate that part of ourselves? Or should we even bother? Who do we listen to? What is the most valuable commodity in the age-of-everything?

Trust.

The United States has massive trust issues. Levels of interpersonal trust in the US are far lower than what one would expect given its level of socioeconomic development.

That’s the word for 20241. Trust. In a world of weird AI girlfriends, uncertain election energy, compounded fear, I truly think that people are going to seek trust. Renee DiResta explores fragmentation and polarization and the consequences of patronage and the disinegration of trust in The New Media Goliaths

In a world where attention is scarce, the political media-of-one entrepreneurs, in particular, are incentivized to filter what they cover and to present their thoughts in a way that galvanizes the support of those who will boost them — humans and algorithms alike. They are incentivized to divide the world into worthy and unworthy victims.

The lack of trust bleeds into everything - media consumption, politics, the labor market, etc. In The Age of the Crisis of Work, Erik Baker discusses social rot, disillusionment with existence, and disastifaction in the workforce, with a takedown line: “This is the real state of work today: skirmishes, but no real battles; a constellation of apparently benign tumors.”

There is so much to be rethought around work, especially considering how it actively works against our internal clocks, as Philip Maughan explored in The Rediscovery of Circadian Rhythms. The importance of aligning ourselves to the natural world supersedes work, as “there may be drugs or interventions out there that didn’t work because they were studied at the wrong circadian time" (!!!)

Baker writes on the tech industry

Once the mascot of American entrepreneurship, the entire tech industry is now in disgrace. The outright frauds (Theranos, Juicero, etc.) occasionally seem preferable to the many companies that are actually disrupting things… Hopes that it might break down social barriers and topple repressive regimes having evaporated, the online content factory serves primarily as a vehicle for people to post screenshots of TV shows that increasingly appear to be written for exactly that purpose.”

The concept of commercialized creativity is explored in the WSJ piece, Streaming Is Changing the Sound of Music, with “the average length of hit songs has dropped by more than 30 seconds since 2000, when it was over four minutes.”

Silicon Valley’s Quest to Build God and Control Humanity is an important article by Edward Ongweso Jr analyzing the importance of understanding the leaders behind new technology (something the OpenAI debacle should have taught us, but I fear we have already forgotten) that ties into The Internet Isn’t Meant To Be So Small, on how social media has destroyed curiosity (people can’t be enticed to leave the app!) with Kelsey McKinney writing

“It is worth remembering that the internet wasn't supposed to be like this. It wasn't supposed to be six boring men with too much money creating spaces that no one likes but everyone is forced to use because those men have driven every other form of online existence into the ground... The internet was supposed to be a place of opportunity, not just for profit but for surprise and connection and delight.”

This idea of incuriosity is expanded upon in The Limits Of The Billionaire Imagination Are Everyone’s Problem with David Roth writing:

It's not just about so few people having so much of everything, although that is plenty odious and offensive on its merits. The problem, as it is experienced moment by moment and day by day, is how little they have done with it, and how little what they have done with it has done for everyone else. That inequality, when compounded over time and amplified by the cretinous and absolutely joyless mediocrity of the people in whose accounts that compounding gets done, winds up not just freezing the world in place, but shrinking it to the size of their own incuriosity.

Kerry Howley did an incredible interview with Jorie Graham, writing how Graham’s work manages to “convey the feeling of time while existing as a person on the internet, overcome, targeted, whelmed by information that never reaches the status of knowledge.” She continues

A life tethered to a phone is a life tethered to a present tense, a stream of insistent notifications (ding!) beckoning the mind back to now. The technology is “fixing us into the absolute present,” she says. “It’s like herding creatures off a cliff or gathering humans into a kind of narrow enclosure where they are highly concentrated, terrified, lulled, narcotized or numbed, driven by scarcity, to survive in the wasteland of the absolute present.” The internet beckons into a flat now, a constant “attending to,” a well of insistent digital need. She notices in the people around her “a sense of shame without a clear source, a sense of scarcity,” a sense of “entrapment.” There is not space for the mind to build a picture of people who do not yet exist.

McKinney also touches on nostalgia, “don't make something new, make the same thing that someone else made very successful, but slightly better.” Nostalgia has shaped so much of our media consumption, for good reasons like social connectedness but also for reasons like ‘pain avoidance as a service’ and as Derek Thompson wrote

“Original stories need to shoot the moon with reviews and buzz to have a chance at $100m, while middlingly reviewed renditions of familiar IP throw up $200m w/o breaking a sweat.”

It’s all about IP too - “a nostalgia play like “Hot Wheels” is seen as a safer bet than an original concept” as Alex Barasch wrote in the New Yorker.

The way we make movies now are strange too. The bodies are uncanny valley, as RS Benedict writes in Everyone is Beautiful and No One is Horny, an idea expanded upon in the brilliant The Puritanical Eye on the passivity of media consumption, the commodification of senses, and

[The] direct result of Americans viewing media consumption as an inherently political act because that is the supreme promise of Western prosperity and the religion of consumerism, and because it’s seemingly all that’s left. We’ve been stripped and socialized out of any real political energy and agency… When the act of consuming is all you have left and indeed the only thing society tells you is valuable and meaningful, the act must necessarily be a moral one, which is why people send themselves down manic spirals deciding what, who is “problematic” or not, because for us the stakes are that high now.

Predictions

So. Oh, but blah blah blah. I fear I have been incredibly negative in this piece. I have three main predictions for 2024 -

Influencer Apocalypse - The girls are not real anymore. It’s very much simulacra and simulation, and the viewers are noticing. Authenticity will be key.

Analog - People love the algorithm, but they are tired. We will return to more vintage forms of production, especially with photography and certain types of graphic design

Learning to live with risk - We sort of had a risk-off year due to people taking various risks post-pandemic. There will be some acceptance of the uncertainty that bubbles under our surface.

Finally, we often forget how good people are. In Elite Panic vs the Resilient Populace, James Meigs talks about the lessons learned from the 1964 earthquake off the coast of Alaska, which reshaped the entire coastline of the state. It ended up being a study in community as people rallied together - no chaos, no fear, just resilience - finding that “ordinary people can make extraordinary contributions—if we trust them.”

I loved this interview with Scorcese -

The whole world has opened up to me, but it’s too late. It’s too late… I’m old. I read stuff. I see things. I want to tell stories, and there’s no more time. Kurosawa, when he got his Oscar, when George [Lucas] and Steven [Spielberg] gave it to him, he said, “I’m only now beginning to see the possibility of what cinema could be, and it’s too late.” He was 83. At the time, I said, “What does he mean?” Now I know what he means.

And of course, I spent a lot of time in 2023, fascinated by time. Time is an object is a beautiful article that talks about the physicality of time (with one takeaway being “this means the Universe is expanding in time, not space – or perhaps space emerges from time, as many current proposals from quantum gravity suggest”). And of course, we can return to literature, with Kierkegaard stating that “[a human being] is a synthesis of psyche and body, but he is also a synthesis of the temporal and the eternal” and Borges writing

Denying temporal succession, denying the self, denying the astronomical universe, are apparent desperations and secret consolations. Our destiny… is not frightful by being unreal; it is frightful because it is irreversible and iron-clad. Time is the substance I am made of. Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am the river; it is a tiger which destroys me, but I am the tiger; it is a fire which consumes me, but I am the fire. The world, unfortunately, is real; I, unfortunately, am Borges.

The passage of time is the only constant. And the time will pass anyways. There is cyclicality to our world, shown in this passage from the New York Times written in 1939 (!)

Finally, a page of all my favorite poems from 2023

.

Thank you for being here.

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice or recommendation for any investment. The Content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.

I am aware of the hypocrisy of stating “everyone is wrong” and then being like “but I am right about this word”

thank you everyone!

Truly amazing how much you can consume, analyse and then summarize for us mortals.