When You Destroy the Tools of Creativity

Lessons from Apple and what Bluey can teach us about trust and agency

I am back! Apologies for the delay! My first book is coming out at the end of the month (you can preorder here, get a signed copy here, and/or enter a giveaway here, if you’d like)

Oh, Apple

Apple released an ad to highlight their new iPad Pro with the M4 chip. That’s fine. Great, even. New technology is phenomenal! But what Apple also did in this ad was use a hydraulic press to crush musical instruments. It was meant to show how skinny-coded their new iPad is, but if anything, it just felt sad. Like oh gosh, they just crushed creativity? Culture? Of course, if their goal was to get people talking, they achieved that.

It was an accidental metaphor1 that hit a little bit too close to home (as Leiris wrote, it’s hard to know where metaphor begins and where it ends). A absolute smushing of things that people love to make another little screen that we stare into. People are comparing it to Apple’s 1984 advert, where the opposite happened - a hammer breaks a TV, turning the world into color, in this ad, the color is stamped out by industrial machinery. Ben Mullin -

In “1984,” a dissident throws a hammer through a TV screen, symbolizing humanity’s power to conquer technology. In this ad, a hydraulic press crushes beloved cultural artifacts, symbolizing technology’s power to conquer humanity.

Oh, Apple. We are in an age of tremendous uncertainty. Trust has evaporated, something I wrote about in my last newsletter. But agency, the individual expression of trust, has declined too - and it’s because of things like this accidentally completely horrific Apple ad.

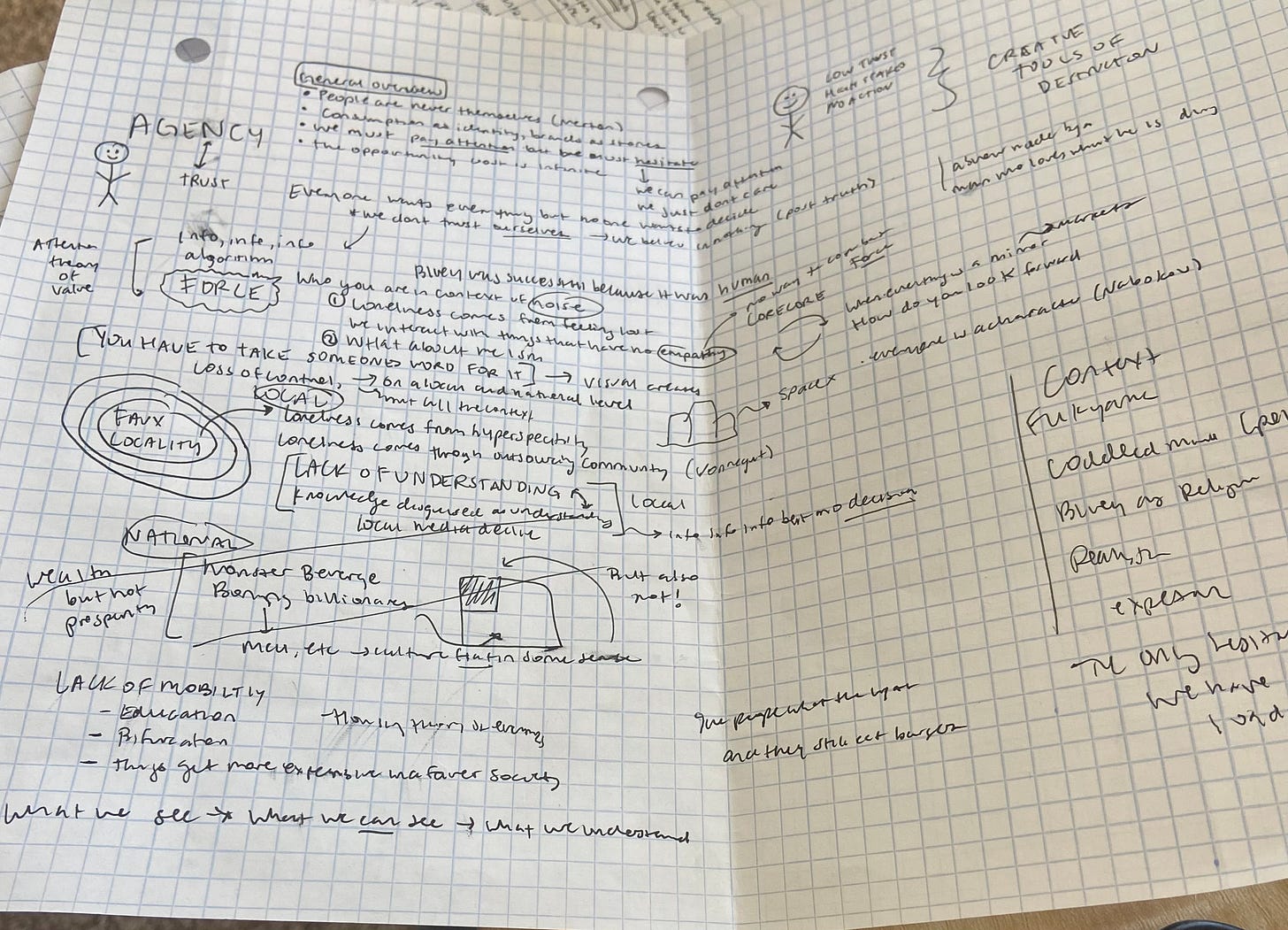

Agency as a Function of Trust

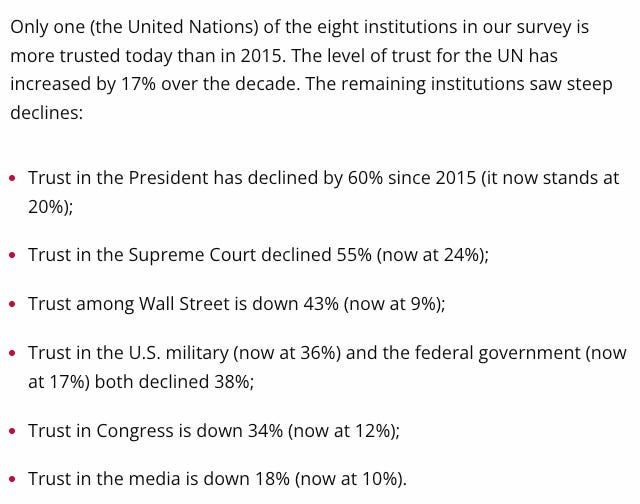

There are all sorts of studies talking about how people don’t trust anything anymore. We don’t trust the government, the media, Wall Street, the President, the military, or each other. And of course, one could point a finger to bipartisanship and polarization, city design and car culture, rage bait and algorithmic incentives as reasons for the decline in trust.

But trust is very big. It happens on a large scale, a somewhat liquid expression of the confidence that people have in institutions, systems, other people. Trust is everything - it’s the foundation for public health, voter turnout, policy preferences, etc. But because we’ve evolved into this strange low-trust high-stakes no-action society, we’ve lost an element of agency, or the individual expression of trust.

Agency is sort of an ephemeral term, one that could fit perhaps uncomfortably well in a conversation at Burning Man. It wades a little bit into the free will debate and determinism and the idea that maybe everything is random anyway and we just fit our internal models to the world around us. But for these purposes, agency, or how people feel about their ability to make decisions, is an expression of trust in the world around them.

And to be fair, we seem to have an element of agency. There are studies showing that people feel fine about their personal financial situation but completely terrible about the national financial situation and showing that people love their congressman but hate Congress (Fenno’s paradox). A perfect petri dish of individual expectations and national outcomes.

And we’ve seen an interesting amount of what seems to be the expression of agency with the rise of things like ‘quiet quitting’ or ‘the Great Resignation’ (which to be fair, could be more an expression of economic strength than individual freedom).

Types of Agency

But there are two types of agency2 - an external locus of control and an internal locus of control - life happens to me (external) versus I happen to life (internal). We clearly have both. For example, people are likely to attribute wage increases to themselves (internal) but price inflation to policy (external) as Stefanie Stantcheva of Harvard has documented.

But, at large, we increasingly have an external locus of control that absolves us of responsibility in decision-making around our life.

In her book iGen, Jean Twenge documents the shift of the youth over the past 60ish years to a more external locus of control.

In her 2004 paper, she talks about the alienation model, how the rise of individualistic values increase egoist tendencies, or blaming bad stuff on other people and crediting good things to yourself.

There are all sorts of negative consequences to this, like higher rates of depression and anxiety.

Everyone wants a God, and because of that, everyone needs a devil. The devil has come in the form of skepticism, the form of distrust, the immediate outrage at anything not immediately familiar. And God is nowhere to be found.

There are the very clear visible culprits to an external locus of control, like structural affordability problems and actual institutional failure, but there are also deep undercurrents of a lack of agency. My theory is that in order to even begin thinking about rebuilding trust, we have to start by rebuilding agency. In order to rebuild it, we have to figure out how it happened.

The Bifurcated Economy

It’s not just polarization and bipartisanship contributing to this trust issue we have (although that is a major contributor) but it’s also a bifurcated economy amplified by faux-locality (a word salad, just in case you’ve been missing your daily greens). But listen - the economy is totally split in half. This is seen in:

The upcoming wave of generational wealth transfer, with some Millennials inheriting a large sum of money from their Boomer parents and many… not.

It’s the people sitting on a golden 2-3% mortgage rate, while those who are trying to buy a house right now use real estate pamphlets to dry their tears.

It’s the labor market that is great for those who have a job, but very difficult for those who are looking for one.

It’s the rise of trade school (Gen Z as the toolbelt generation) and the (deserved) mini-rebellion against the cost of a college education.

It’s the stability in hospitality and healthcare industries, as tech and finance experience ‘white collar recessions’.

It’s the 400 richest Americans holding wealth equivalent to about 17% of GDP, a 15% (!!) increase from the 2% level in 1982.

The bifurcation is dug deeper by an aging society that tends to vote in its own self-interest. Not to belabor an ancient point, but our two presidential candidates are…ancient. But it’s complicated. 25% of Americans have no retirement savings, despite the baby boomers being the richest retiring generation we have ever had, according to Ed Yardeni. Childcare costs are up 32% since 2019. Fertility rates are low and the old are only getting older.

This creates a Portugal-like situation, which as Palladium wrote, is nearly impossible to escape. “As the country struggles with an aging population, brain drain, and youth drain, it also suffers from the impossibility of voting structural reforms into existence.”

So. And that’s the interesting thing about the near universal decline of trust is that it’s happening across a fragmented reality. It’s happening across all of these various fault lines - many of which are exhibiting signs of cracking - demographics, wealth, housing, labor market, whatever the heck AI is going to do to various jobs. There are people in the U.S. who might as well be in entirely different dimensions of the universe, but everyone agrees on not trusting anything anymore, which is beautiful in a way that only terribly ironic things can be.

Force

So we have a completely divided economy, rife with polarization, that exists in a state of Simone Weil’s ‘force’. This is described “x that turns anybody who is subjected to it into a thing… it makes a corpse out of him. Somebody was here, and the next minute there is nobody here at all.”

There are plenty of examples of force in modern life.

The mindloop of the algorithm.

The flashing advertisements on subway trains and along highways.

Politics as theatrics, theatrics as underfunded last gasps of hope.

The smushing of instruments, perhaps

It makes us little shells of ourselves.

Force shows up in media headlines (did you know, a negative headline increases the clickthrough rate by 2.3%? and a positive headline decreases it by 1.9%? Please, someone, the incentives are screaming), clearly exemplified by the Briefing Book’s deep dive into ‘bad news bias in gasoline price coverage’.

Force is companies like Apollo making bets on death, and companies like Bank of America fostering such an unhealthy culture that it results in death.

The Faux-Locality

All of this exists in a faux-locality (the Internet) where Big Problems are very accessible and very tangible and very much all around us all the time. I think it looks something like this - the Bigness of the universe getting shrunk down to the size of your palm.

But that doesn’t mean the problems are palm-size solvable. It’s knowledge disguised as understanding, information that is actionable, but not in a series of quick, easy steps. The Internet is a campfire, certainly, a tool of connection and beauty but it’s also extraordinarily overwhelming. So we engage with things in this hyperspecific way, and when our personal tools, which are only really designed to address things in our true locality fail us, we lose hope.

For example, things like the housing crisis are fundamentally terrifying because there really isn’t much anyone can do about that. There are actions like voting for people who might make it easier to build, attending city council meetings, and maybe starting a construction company, but it’s a big problem that requires big solutions.

You see, we can pay attention. Contrary to popular belief, we can absolutely tune in, and we do (perhaps to questionable mediums, like getting news from social media). The problem is not that we can’t pay attention - we can - but we have no motivation. We do not care.

And the issue here is as Simone Weil highlights:

Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer. Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer. If we turn our mind toward the good, it is impossible that little by little the whole soul will not be attracted thereto in spite of itself.

We are what we attend to. And so if we are circling the drain of media negativity and reality TV-ification of politics and remaining lost in the crevices of our faux-locality where our attention is harvested for ad dollars, it is no wonder that we are overwhelmed and sad and feel flattened in terms of responsibility.

It’s Jonathan Beller’s attention theory of value, where exploitation of attention is immensely profitable. Everyone is a business, as Mark Fisher highlights in Capitalist Realism. Even you. Especially your data.

So people get nostalgic. No need to make a decision if you can simply blame the times. That’s a natural reaction to a perceived loss of agency, leaning into the idea that nothing should change but everything should be different. A tweet “yearning for the days of the literal Great Recession based on a single loss-leading promotional item from Taco Bell comparing the DoorDash price instead of the real price ($3.69)” has 53k likes.

Nostalgia is escapism. Nostalgia is a pleading for the past, for familiarity. So we do that, or we invent problems.

There’s a passage from Fukyama that ties it together -

Experience suggests that if men cannot struggle on behalf of a just cause because that just cause was victorious in an earlier generation, then they will struggle against the just cause. They will struggle for the sake of struggle. They will struggle, in other words, out of a certain boredom: for they cannot imagine living in a world without struggle. And if the greater part of the world in which they live is characterized by peaceful and prosperous liberal democracy, then they will struggle against that peace and prosperity, and against democracy.

Struggling for the sake of struggle is a very applicable concept. And to reiterate, there are real problems with structural affordability, and institutional failure, and tech people that got far too rich extracting far too much from the world. Please, listen to that. We absolutely have fundamental problems as a society. Money is in all the wrong places, as the Defector highlighted.

But a lot of people bemoan the system that they very clearly benefit from, a struggle to struggle. Which is fine, but they provide no solutions to fix it. With concepts like financial nihilism, the opportunity cost is infinite when everything is at the tip of your fingers, everyone wants everything but no one wants to decide. Noelle McAffee wrote:

The qualitative difference between public opinion formation and public will formation is that the former only calls on us to opine, to mouth our preferences. The latter calls on us to decide. If the public is considered merely as generators of public opinion, then we have the problem of our travel plans. Everyone wants everything, and no one need decide what the right ends are or how to achieve them. We will get a cacophony of competing claims, disagreement without deliberation or choice. The bar needs to be raised for public discourse: don’t just tell me what you like; tell me what you want to do - and what you are willing to give up. And tell me you are ready to do this.

Tell me what you want to do - and what you are willing to give up.

What do you want to do?

Taking Someone’s Word For It

I was at NATO HQ in Brussels 3 weeks ago, and we talked about developing belief in the post-truth society. How do you even begin to develop policy around nonbelief? And it’s made doubly hard by things that Virginia Postrel described beautifully in her interview with Brink Lindsey on The Permanent Problem

"People want to feel smart and they want to feel in control...[But] inevitably, all these great technological wonders come from specialized knowledge...When there is something new that you can't see the immediate positive effects of, you have to take somebody's word for it.”

You have to know what you want to do in a world in which progress can sometimes feel as backwards as smashing instruments for the sake of another screen. You have to know what you want to do in a world where progress isn’t always visible. You have to know what you want to do in a world that harvests dopamine, demands attention, and isn’t always beautiful.

The only way that we battle force is through beauty and through empathy (all the woo weaponization). Anne Carson did a beautiful interview in The Paris Review where she talked about hesitation. She talks about how there was space between things like looking up the definition of a word and actually understanding the word. But now, we don’t have that moment of pause, an interval to reflect. She says -

”That interval being lost makes a whole difference to how you regard languages. It rests your brain on the way to thinking because you’re not quite thinking yet… It’s not that—it’s on the way to knowing, so it’s suspended in a sort of trust. I regret the loss of that.

The only hesitation we have is loading time, the spinning wheel on our computers, a clock clicking in the kitchen, in time to our heartbeat.

A Quick Aside on Bluey

I want to something that is very beautiful and supersedes faux-locality to fight force. There is a children’s TV show called Bluey3, which follows a family of anthropomorphic dogs and their life in Australia. The lineup includes Bluey, a 6-year old Blue Heeler puppy, and her family: her dad Bandit, her mom Chilli, and her little sister Bingo.

Bluey is an Australian TV show that premiered in 2018 created by Joe Brumm who wanted to portray what it was like for kids to be kids through an Australian version of Peppa Pig. Brumm has two little girls and wanted to create a show that draws on his real life - the highs and lows of being parents, being a family, being kids.

The lessons are about conveying these seemingly simple ideas of sharing and playing, but they are also about riding bikes and cleaning the house and hungover parenting, infertility, and making adult friends, and what it means to belong or to not belong at all.

Bluey is successful because it is human (ironically enough).

In one episode, ‘Stickbird’, Bluey and her family go to the beach. However, Bandit is clearly struggling with something, lethargic and sad. When Bingo’s sand castle gets knocked over, he utters “When you put something beautiful into the world, it’s no longer yours, really.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about that. I’ve been thinking a lot about how this show resonates with both parents and kids, and what it means to create something beautiful.

Brumm reminds me of the creator of Calvin and Hobbes, a comic that he mentioned he got inspiration from. In talking about retiring from Calvin and Hobbes, Bill Watterson says “My approach was probably too crazy to sustain for a lifetime but it let me draw the exact strip I wanted while it lasted.”

Joe Brumm has managed to “cultivate the art of staying true to the hazards, vulnerabilities, mysteries, and perplexities of reality, because ultimately that is our best chance of remaining human” as Lyndsey Stonebridge wrote. Sometimes, we can only see ourselves through mirrors, and Bluey is just that - a reflection for parents to see themselves, so they can see their kids. The kids see themselves in the characters and the stories but it also helps them to see their parents as people.

Bluey is a form of beauty, one that is relatively rare. There is more of it now, especially if you know where to look. As Steven Nightingale wrote in The Paradise Notebooks

In the experience of beauty, we learn to tell things alike; to move from the darkness of oneself to a sympathy, an open rapport; a longed — for, conscious union with the world. Beauty is a lucid and graceful assembly of forms that calls the mind close to life, our bodies close to the earth, and all of us closer to one another.

I think Bluey is one of the most beautiful things of the past half decade. And it’s lessons in humanity, in decision-making, in seeing people as people outside the faux-locality, as treating it’s audience as bigger than a nonthing, is something to learn from.

Yeah, it is a mess. But

Things are cracked. The only way they get uncracked is through restoring agency.

Thomas Merton once wrote:

“Many poets are not poets for the same reason that many religious men are not saints: they never succeed in being themselves. They never get around to being the particular poet or the particular monk they are intended to be by God. They never become the man or the artist who is called for by all the circumstances of their individual lives… They wear our their minds and bodies in a hopeless endeavor to have somebody else’s experience or write somebody else’s poems.”

We must make it so people can be themselves. The way to rebuild trust comes through rebuilding agency in an individualistic society. Geoffrey Hill says that

Difficult poetry is the most democratic, because you are doing your audience the honor of supposing that they are intelligent human beings. So much of the populist poetry of today treats people as if they were fools. And that particular aspect, and the aspect of the forgetting of a tradition, go together.

Apple did destroy tradition too, seemingly on accident. But people certainly aren’t fools. To rebuild agency, we need to be transparent about the problems. We are divided, economically and politically. We are surrounded by a force that wants us to wither into skeletal memories of ourselves. There are incentives to crush things to bits with a hydraulic press in the name of consumerism.

A lot of rallying cries, but the basic idea is that in order to re-establish societal trust we must re-establish motivation and care on the individual level. Work on media literacy. Work on financial literacy. Education is a toolkit, and we have forgotten that I think. The institutions are a nightmare (Derek Thompson, of course, wrote on it recently) and the world will never be perfect.

But we have to believe in each other. Create beauty in our true locality. Give each other the tools to hack away at things, one step at a time. We must decide, and with conviction. And finally, with things like Bluey, it is clear that there is room for transparency, for stories, for a bit more humanness, and for beauty.

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice or recommendation for any investment. The Content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.

And many people liked the ad! They said don’t take the commercial so seriously. So I am here to take it seriously.

I am being rather loose with my terminology, do forgive me

A version of this research was first published with the TLDR podcast

"Work on media literacy. Work on financial literacy. Education is a toolkit, and we have forgotten that, I think."

Fighting nihilism is such an uphill battle, getting people to read and research and educate themselves is a struggle in of itself. And then to have optimism in spite of that education! "If you stare too long into the abyss, the abyss stares back." The more you learn, the harder it gets to strive for the silver lining. But, I think it's the responsibility of us optimists to do a better job of painting that future we want to see come true rather than hyping up the doom.

"With every future we wish to create we must first learn to imagine it." - Chen Qiufan

If you haven't yet (oh no another addition to the reading list), Neil Howe's The Fourth Turning is Here has some insights on the generational aspect of why trust is declining. I am still not sure about his juxtaposition of the linear approach to life - we have agency to keep the futurer moving in a line - versus cycles - we move within them and they outweigh our agency (though don't remove it entirely). Glad you are back to the newsletter...