Good morning from South Carolina. The tariffs are here. A brief explainer of what’s going on.

A Fake Headline and the Stock Market

Earlier this week, the stock market soared on a fake headline that said President Trump might pause new tariffs for 90 days. It then fell back down hours later when it turned out the Twitter account Walter Bloomberg (an account not affiliated with Bloomberg and who has shown signs of being an actual human a few times) had somehow copied some a headline from somewhere (or perhaps decided to manipulate markets a bit, who knows).

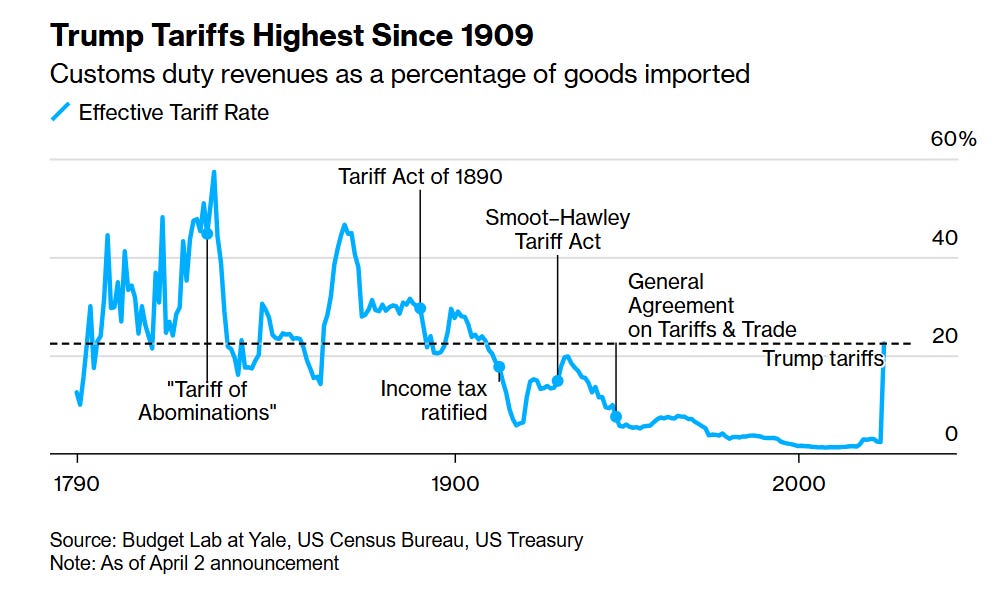

The market reaction was important because it shows how desperately the market wants tariffs to be over. Investors were so ready to believe any sliver of good news1 that they rallied on something that wasn’t real. And so far, the administration hasn’t given them any at all. Into Tuesday, markets were brimming with hope, trading mostly upwards, before giving an exasperated sigh and tumbling down as we all settled into the realization that these tariffs are coming. And they did. At 12:01am on April 9, the largest tariff hike in US history went into effect. In fact, the tariffs are so punitive that they started making less money, as Ernie Tedeschi wrote.

And there are a lot of questions here: Why have visions of a 1950s factory‐floor America overshadowed the realities of modern labor and technology? Are bonds broken? What is Congress going to do? How is China reacting? And what do we do next?

What’s going on with bonds?

So first, bonds.

The bond market is selling off, right in the middle of a stock market meltdown. The US is risky to the world right now and it has momentarily broken the markets. Here are some headlines to give you a sense of how turbulent things are.

Stocks are going down because tariffs will affect the real economy. Normally when stocks go down, we would see a flight to safety - the markets freaking out, so people are like “Well, you know what seems safe? US debt. The US is a safe, stable country, so I’ll buy up some Treasuries! Nothing can go wrong!” So they buy Treasuries, push bond prices up, and yields down.

But now, that isn’t the case. Yields are going up, meaning people are selling bonds, which could be the sign of a new era. Why? A few reasons:

China is dumping: Perhaps the bond selloff could be because China or other foreign governments are selling US Treasuries2 out of spite or fear.

Forced selling: Perhaps it’s the basis trade unwind as Matt Levine explains as the market deleverages, fueling forced selling, and various hedge funds blow up.

Safe Haven Status: Maybe everyone’s just spooked that the “safe place” isn’t so safe anymore. If other countries think the US government could yank Fed swap lines for political gain, or suspect the White House might keep piling on tariffs until the economy cracks - maybe they decide, “Well no Treasuries for me, thanks.”

Narratives: It’s really whatever people are saying about things. Vibes do matter because they are a leading indicator for actual data and positioning.

And this gets into the tricky part - when and how does this stop? EVERYTHING is down - the dollar, oil3, bond prices, equities, credit spreads are spiking. This is very bad for the housing market too. Everything is going exactly the way it’s not supposed to. And what can anyone do?

Could the Fed or Congress Step In?

So maybe the Fed intervenes right? But the Federal Reserve can’t exactly cut rates when inflationary pressures are so high because tariffs and would rather tread water, as SF Fed President Mary Daly said. But maybe the Fed can do some QE and buy up some bonds, but that would create even more inflationary pressure.

Congress could also step in. It is their job. Remember, all of this is being done underneath the guise of emergency action. They can literally stop this at anytime. As the Washington Post writes “7 Republican senators are backing a bipartisan bill that would scrap new tariffs after 60 days unless Congress votes to approve them.” But they need at least 2/3 of senators (and 20 Republicans) to override Trump’s presumed veto. They don’t seem to want to do that.

And so some senators - especially those from manufacturing‐heavy states - could push for more targeted trade deals to blunt the impact of tariffs on local businesses. Others, particularly where agriculture is a major employer, could lobby for carve‐outs or partial tariff relief if other countries retaliate against American farm exports. There could already be a bail-out on the way for farmers, like we had during the first set of tariffs (which negated any revenue collected from those tariffs, but anyways)

At the state level, governors could negotiate local business partnerships or foreign direct‐investment deals. For instance, a state could offer tax incentives or simplified permitting to try and bring companies to build factories there, effectively creating mini-trade or investment zones. This would put states in tension with White House policy, but states will need to protect local jobs.

Really it’s the federal government: The ideal situation would be for the administration to call off the tariffs, but when policy is pageantry, that doesn’t happen. Trump is not replying to anyone on negotiations as of the morning of April 9th, according to Politico (but they are “kissing his ass”) and now he is talking about tariffing pharmaceuticals.

The problem with the whole yields thing is that the administration wanted to get them lower so they could refinance the debt at a lower rate, reduce interest payments, and ride off into the sunset or something as I wrote about here. But now, not only is there a potential recession on the horizon, but yields aren’t any lower - a perfect stagflationary combination. High inflation, low economic growth, and high unemployment.

What happens to the World Order?

If you’ve been reading my last few pieces, you know I’ve hammered on these tariffs for a while (even before the election, when I first interviewed Erica York from the Tax Foundation). The administration is basically demanding that other countries either pay new fees to trade with us or else.

And so - what is the US to the rest of the world? A lot of people think that the US is subsidizing the rest of the world, when it’s really the opposite, as Ben Hunt wrote about.

The US was the prime beneficiary of a stable, trust‐based global system. The rest of the world has really subsidized the American lifestyle. This stable system used to be called Pax Americana, where for nearly 80 years, the US gave other countries security, open trade lanes, a stable dollar, etc. in exchange for them conceding broad US influence over global rules and institutions. So the US enjoyed unique privileges, like cheaper borrowing costs and the ability to run persistent trade deficits (which aren’t a bad thing) while other countries’ demand for dollars and Treasuries effectively subsidized its standard of living.

Now the US is turning around and demanding a fee that doesn’t match to any type of math (in fact, the math used is wrong as AEI wrote about). So countries start asking: “If the US is going to nickel‐and‐dime us for every container ship and submarine, maybe we’ll just build trade deals with each other, avoid the drama.” So we end up pushing them away and melt down our own advantage, the trust.

So it’s all changing and maybe the reserve currency too. We used to have one big question: “Will China dethrone the dollar?” That’s probably too simplistic. We might instead see a bunch of “currency clubs” forming, as the IMF has wrote about before, like small blocs or bilateral deals, some anchored in digital clearinghouses, some in partial pegging, each cutting reliance on the US bit by bit.

Rather than a single rival currency taking down the dollar, we could get this mosaic that collectively reduces US sway. The net result is the same: less automatic demand for Treasuries, more fragmentation, less “safe haven” reflex.

How is China Responding?

A lot of people are saying that the ultimate end game here is to decimate China. Treasury Secretary Bessent said that they could remove Chinese stocks from US exchanges because “everything is on the table” and China has retaliated with a 50% tariff on US imports. So we are officially in a trade war.

The yuan is down as China devalues their currency to try and make their exports look more attractive (which is so complicated and has so many secondary effects) and presumably preps for maybe a capital war with the US. China is a tough opponent for many reasons:

They don’t need the US like they used to. They diversified who they send exports to (Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia). and the US just really isn’t that big of a piece of the pie. Some people will argue “well the US will bankrupt all countries with these tariffs so that way no one can afford to buy from China” which really feels like taking the chess board and spinning it around in another dimension - but perhaps it’s true.

They are able to withstand much more pain than the US. This is a complicated argument, but the American public was irate during the last year of the Biden administration because of inflation. If that comes back up again with tariffs (which it will, Trump’s first term tariffs drove import prices up), it will likely torch Trump’s polling (maybe?) although the administration seems to think it will solidify their stance with Main Street (and Main Street and Wall Street are basically the same thing at this point, let’s be real)

China has good factories. They do not fear automation as some people in the US do. They have factories that are entirely autonomous.

That’s not even mentioning how many high‐end electronics, batteries, and basically everything on Amazon still runs through Chinese supply chains. So if the US truly wants to isolate China, there will be massive price increases, and so again you can guess how that might go over with American consumers who are used to inexpensive things.

We assume big trade blocs are decided by governments. But remember, tariffs are paid by companies exporting to the US, not the countries. And increasingly, corporations, like Apple, Samsung, etc will likely have to do their own foreign policy of sorts to ensure continuity. They might have to form new shipping lanes and manufacturing footprints outside the US creating a quasi-private global network that could eventually become more important than official Washington–led institutions. However, it’s of course complicated, because as Scott Galloway talked about, Trump has really done a number on America’s brand, which hurts American companies.

The Myth vs Reality of Reshoring

Part of the official rationale is “We’ll just make everything here.” And that gets into the administration’s hyperfixation on bringing back old‐school manufacturing. A few things:

We already had manufacturing growth: Manufacturing actually has boomed over the past four years without use of broad tariffs as Joe Weisenthal pointed out underneath the IRA and the CHIPS Act

They are yearning for an era that is gone:The administration has talked about lines of workers bolting in cellphone screws just like we used to in the 1950s or something (Trump specifically likes to compare us to the “golden age” of 1870 to 1913, because we didn’t have an income tax). This resonates politically to a certain extent: nostalgic images of steel mills or assembly plants symbolize American economic power, when the US was the only country post-World Wars that had the capacity to build. That time is over.

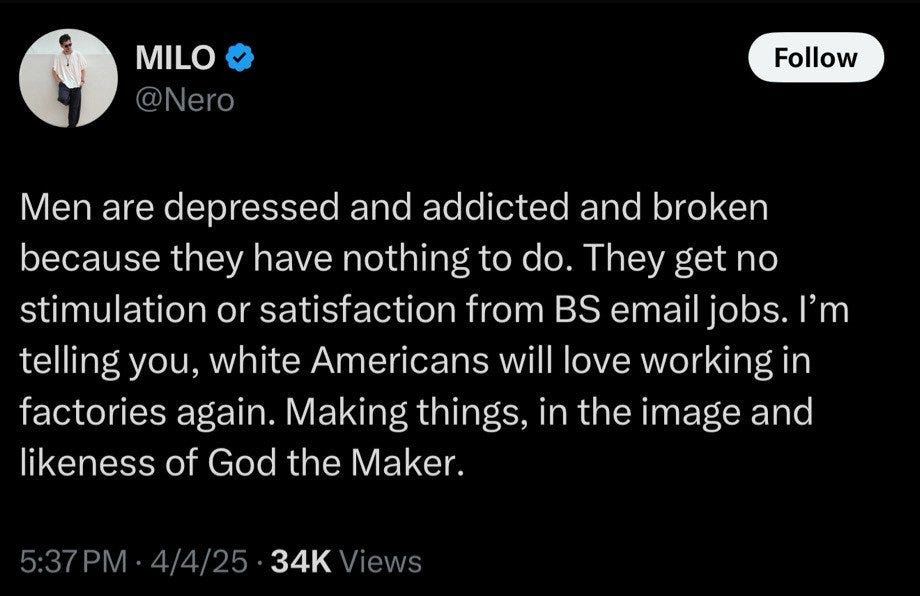

This will not solve our societal problems: A lot of people are acting as a spokesperson for the everyday man, like the guy below. People left manufacturing in droves once they could - and that’s not to say that the work isn’t important (it’s extremely important!) but it’s complicated.

Anecdotes: Then you read what Gary Cohn said to Trump in his first term, as Jordan Schneider shared. People were leaving manufacturing, and part of it is because it’s really tough and menial work. We have gotten much better at using machines to make it better, but if people have the option, they are going to choose the job that isn’t sticking little screws into phones. Instead, they are going to choose working on planes or maybe working in a fab (if only someone hadn’t cancelled the CHIPS Act!)

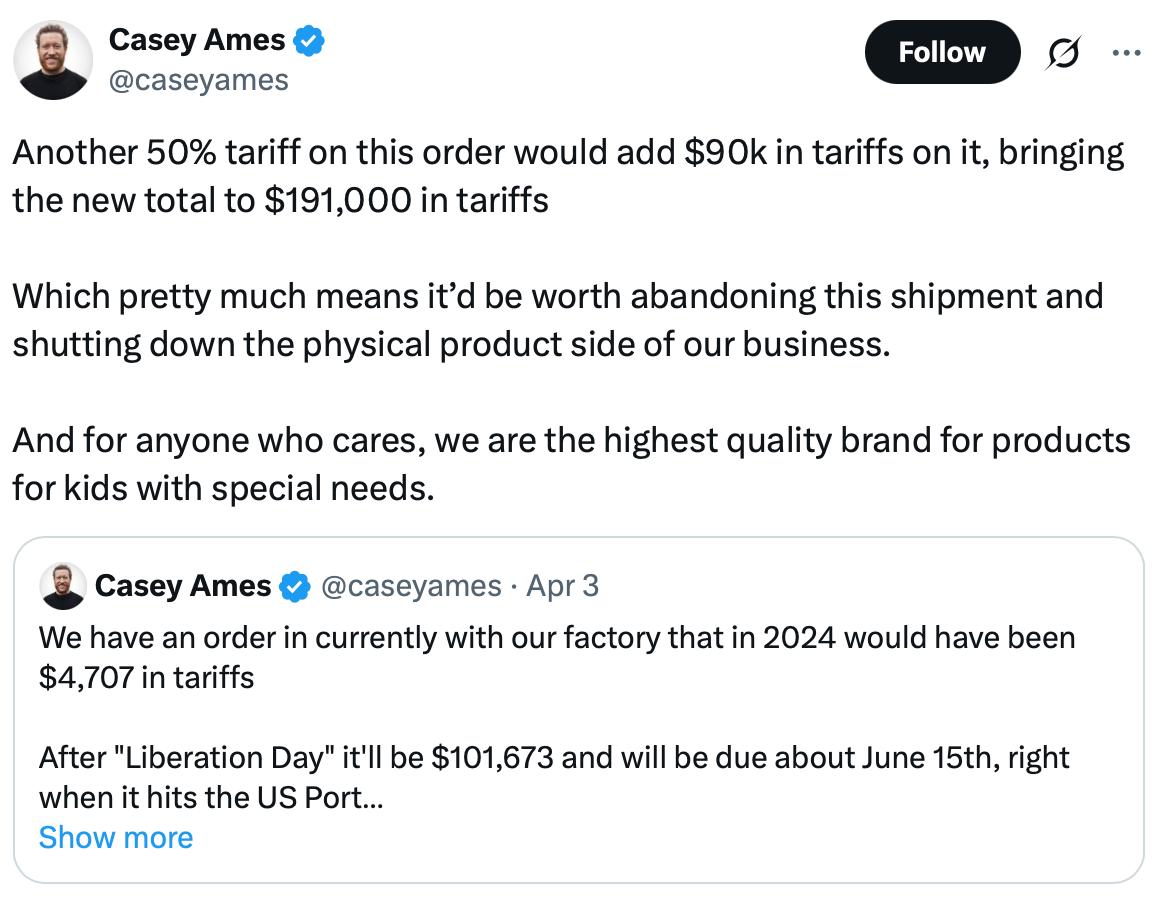

It’s not just Wall Street: David Bahnsen put together a list of how the tariffs are impacting Main Street and there is a lot of concern and a lot of fear. To say this will address the loneliness crisis or whatever completely misunderstands what’s rotten in our world. It’s the phones and a housing crisis. We were at full employment when Trump took office.

Finally, this will not bring that many jobs back: Modern factories also run with a fraction of the labor they once required. The administration admits this. The manufacturing jobs that exist today often demand advanced skills, like programming CNC machines, for instance, which require workforce development, faster permitting, and other things beyond taxes as Alex Tabarrok covers well.

This creates a lose-lose-lose-lose-lose situation.

If we do onshoring but staff it with robots, we get neither cheap foreign labor nor large domestic hires.

So you might see fewer foreign supply chains (less soft power for the US) and no big wave of new American jobs

Manufacturers are actually pulling back on spend in the face of uncertainty, like what we’ve seen from Haas Automation (a company that makes CNC machines) and Microsoft now isn’t going to build their $1B data centers in Ohio (costing 1,000 jobs and $150 million per year for the local economy)

Trump is trying to cancel the CHIPS act, so it’s uncertain how real of an argument this all is. If you wanted manufacturing, you’d keep that!

Companies have stopped giving guidance for the future, as Sam Ro wrote about.

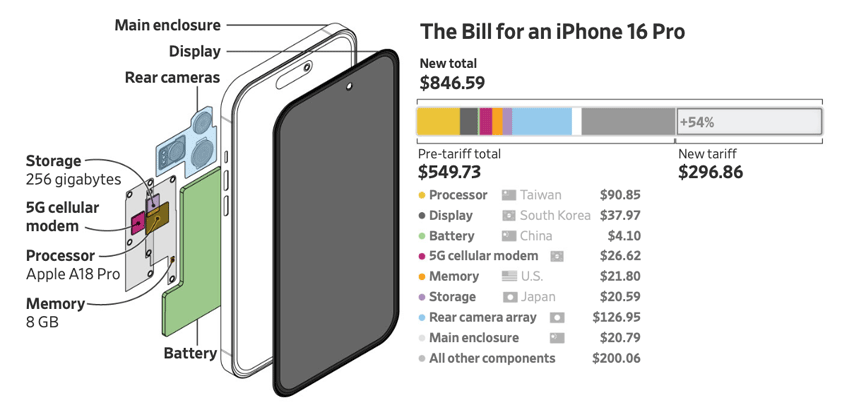

Even if we do onshore - like Trump believes that the US can make iPhones4 - it would be very expensive. The WSJ has a tremendous article about what it would look like to make iPhones with tariffs - and outside of the sheer effort and cost of moving things to the States, the phone itself would be extremely expensive.

Within this manufacturing discussion, there is also a huge focus on goods and making stuff instead of acknowledging what the US is good at, which is financializing stuff. As Matt Levine wrote

Right now, many foreign countries sell goods to the US, get dollars, spend some of the dollars to buy goods from the US, and use the rest to buy US financial assets. In the Trump system, they will use all of their dollars to buy goods from the US, and no financial assets.

Instead of our stocks and bonds, other countries will now have to somehow buy things the US makes, which will

Have to be things cheap enough that developing nations can afford to purchase them which would

Require a drastic reduction in standard of living in the US to make cheap enough things to sell abroad.

So yes, we run deficits in goods, but surpluses in services - finance, software, media. If the rest of the world develops parallel entertainment, payment systems, or capital markets, we lose that intangible advantage.

There is also zero acknowledgment that we can’t make chocolate or bananas or other raw materials in the US5. Some people will say “oh that’s fine, I don’t need to eat bananas” but that’s a narrow-minded view of how the world works. For example, Mr. Beast constructs his little chocolate bars in the US but imports raw ingredients from abroad because we don’t make cocoa here. So sure, you don’t need to eat bananas, but what about all the small businesses (or giant YouTubers) that rely on things we simply cannot make here?

Take coffee for example. I have had two cups of coffee editing this piece this morning. The beans are from Colombia. We cannot grow those coffee beans here because the US doesn’t have the proper climate. So we have a trade deficit in coffee - but that isn’t bad, because Colombia has a comparative advantage in coffee. So we buy their coffee, because Americans love coffee, and they get US dollars that they spend on other things. Everyone benefits.

And that’s the frustrating part - we shouldn’t dream of making socks here. The real pivot to the US is advanced technology like AI, chips, biotech. By decoupling or punishing foreign partners, we might accelerate them building their own R&D ecosystems. If they succeed, they’ll rely less on this really important American technology. Then we’re not just ceding a shoe factory or whatever, we’re ceding the next wave of innovation. That’s a deeper, darker implication.

Potential Next Steps for Policy

Ray Dalio has come out and said “hey everyone, it’s not about the tariffs, it’s about all the debt and we need to rebalance it eventually” and there is of course truth in that. He highlights that we are just in a world that is blowing up a bit.

And Dalio is right. We’re talking about an entire ecosystem of trust that took decades to build. Up until recently, the world was okay funneling money into Treasuries and letting the US call a lot of shots because they believed we’d be a somewhat consistent hegemony.

If we keep lashing out unpredictably, or treat alliances like subscription fees, that intangible trust fizzles, and so do all the benefits we reaped from it - like cheap borrowing rates, supply chain stability, and a seat at the head of every negotiating table. Dalio’s ‘Overall Big Cycle’ is here, but torpedoing the world into an economic downturn and kneecapping industry probably isn’t the best solution to fix it.

Even if next month the White House says, “Oh, never mind, no more tariffs!” the rest of the world has now glimpsed the risk that we could do it again. That’s enough to push them to form backup plans - like forging more robust trade ties with each other, or seeking alternate reserve currencies.

What should the US do instead?

Target actual trade abuse Focus on verifiable IP theft, forced tech transfers, or unfair subsidies. Instead of slapping blanket tariffs on entire sectors, create narrow carve‐outs (like for the shrimpers) or penalty rates only for proven violations and reduce collateral damage for U.S. businesses.

Invest in Workforce & Tech: Bring back the CHIPS Act! High‐tech manufacturing incentives encourage fab building in the US without punishing consumers with broad tariffs. Fund vocational training, apprenticeships, and community college programs.

Smart Industrial Policy: Modernize roads, ports, and broadband to reduce supply chain frictions and boost domestic competitiveness. Instead of tariffs, use incentives to attract high‐value industries, especially those critical to national security.

Reinvigorate Trade Alliance: Improve USMCA, or rejoin modified TPP (CPTPP) under terms that protect domestic interests

Global Leadership: Show consistency in policy, stop tweeting, and demonstrate a willingness to stick to negotiated terms.

Hopefully. But what’s next? We could imagine a few scenarios:

Slow Fragmentation. The trade war never hits a single dramatic meltdown, but the global system gradually rewires itself. Over time, the US is just one big player among many, not the gravitational center.

Partial Climbdown. The administration sees a recession looming and discreetly unwinds some tariffs. Markets calm down a bit, but the damage is done, and trust remains low.

Full-Blown Crisis and Rebuild. Something snaps.- like massive Treasury dumping or a meltdown in supply chains - and everyone rushes back to the table for a new Bretton Woods. The Us gives up some privileges to restore stability.

None of these look exactly like the old normal, because once the illusions of reliability or hegemony are shattered, you can’t just re‐mint them. Sure, we can maybe salvage an equilibrium, but it’ll be on new terms.

Meanwhile, near‐shoring might skip us, allies might shrug off our big threats, and we might find that a cunning “automation plus tariffs” approach doesn’t actually create a ton of manufacturing jobs anyway.

Tese tariff wars and bond panics are about more than short‐term headlines. They might reshape how capital flows, how supply chains form, and how the world cooperates on everything from financial crises to war. And we might not see a single cataclysmic day - just a series of smaller breakdowns that add up to a world where America isn’t the anchor it once was, and everyone else has moved on.

Once we blow up the intangible architecture of trust, a partial walk-back won’t fix it. If we don’t see this soon, we may wander through a patchwork of mini crises and alliances, ironically discovering that the old system - flawed as it was - was actually the best deal the U.S. ever had.

Meanwhile, even if some domestic supporters believe tariffs can fix decades of uneven trade practices, we run the risk of hobbling ourselves more than we help. A smarter approach would combine targeted enforcement of legitimate trade abuses, real support for high‐tech manufacturing, and genuine leadership on the global stage. Without that, the American consumer will keep paying to throw away the very trust that made us a superpower in the first place.

What can you do?

None of this is investment advice, just ideas.

Check your portfolio mix: Make sure you know how much of your investments are in stocks, bonds, and other assets. Consider diversifying abroad. Make sure you understand any ETFs or mutual funds that you hold. Holding some mix of equities, cash, different bond maturities, or even other assets (like real estate) can help balance risks.

Cash Reserve: If markets get rocky, having a few months of expenses in cash (or something very close to cash) is a good cushion. It keeps you from being forced to sell investments at a bad time.

High yield savings account: If you’re risk‐averse, stick it in a HYSA. You’ll earn a yield and can exit fairly quickly if needed. I have about half my portfolio in this.

Don’t panic sell: Headlines can sound frightening, but panicked selling rarely helps. If you have a diversified, long-term portfolio, short-term volatility is often just noise.

If you see alarming headlines, don’t let fear dictate your moves. This uncertainty won’t go away anytime soon, so stay calm, know your time horizon and adjust your portfolio’s risk level to something you can live with. Thanks everyone.

I have talked at length about tariffs in many previous newsletters, and have interviewed Erica York of the nonpartisan Tax Foundation four times now (as well as Stan Veuger from AEI) and no one likes them!

Foreign investors own 18% of the US stock market so this could really get rough

It is unprecedented for oil and bonds to crash at the same time. Russia isn’t very happy about this

Consider the inputs here - processors, display, camera modules, memory, battery, glass, chips, casing, assembly etc - it’s complicated and would take a long time to build out here

And there is an important note to make about the labor side of all of this. It is true that we outsource a lot of externalities to other countries and they get paid very little for very hard work. Some of it is that the development ladder - like yes, the work is hard and the pay is little, but an emerging economy’s factory wages might be better than the alternative. Things don’t get perfect all the sudden - but blanket tariffs don’t solve that complexity. They can actually make it worse if thousands of people lose factory jobs and revert to extreme poverty.

So detailed, researched well and real life examples (coffee). Thank you!!!

The depth of knowledge here is absolutely astonishing. I love the exploration of the second order effects we’re about to see.

And I agree, the worst casualty to come out of this fiasco is the death of trust in the American system. That will pay off in long term pain for years if not decades.